Augusta Read Thomas concerto to receive world premiere by Lynn Harrell and BSO

Augusta Read Thomas’s Cello Concerto No. 3 “Legend of the Phoenix” will receive its world premiere Thursday night by soloist Lynn Harrell and the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Christoph Eschenbach. Photo: Michael J Lutch

Augusta Read Thomas is a composer, but poetry and visual art are almost as vital as clef markings and staff lines to the dramatic, inherently joyful music she writes.

Boston Symphony Orchestra audiences will get a taste of that heady blend in this week’s world premiere of her Cello Concerto No. 3, Legend of the Phoenix. Lynn Harrell is cello soloist, and Christoph Eschenbach, who has conducted several Thomas world premieres, will be on the podium.

Of the100-plus works Thomas has composed since 1990, all have poetic titles or subtitles, more often than not evoking images of ancient legends or the cosmos. They range from Vigil, her first work for cello and chamber orchestra from 1990, to Astral Canticle, a work for full orchestra. Commissioned by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra where she was composer-in-residence from 1999 to 2006, Astral Canticle was a finalist for the 2007 Pulitzer Prize.

As for visual art, the 48-year-old Thomas starts a new piece by literally drawing a map of how it will unfold—using lines, shapes and colors to outline elements such as harmonic shape, rhythm and overall form.

“When I compose, I don’t make a short score or piano reductions,” said Thomas. “I go from sketches directly into full-score pages, which I write on manuscript paper with pens, rulers and Wite-Out. The sketches are like architectural guide lines—or potent bullion cubes from which I can start to imagine how to cook a whole meal.”

The final sketch for the general outline of Legend of the Phoenix resembles a city skyline. Vertical shafts rise like skyscrapers from a flat base line that represents the concerto’s 30-minute running time. At various points, the skyscrapers, outlined with Easter egg pastels, bear labels like “Fanfare, Blazing” and “Rich-Robust.” A dark line representing the cello runs through the skyscrapers, shifting from straight and uncomplicated to undulating waves. Its final rise is as steep as a rollercoaster’s.

Curved arches float above the skyscrapers like so many rainbows, each accented with a different pastel. Some indicate expression markings—“majestic,” “whimsical, sprightly, playful.” The four largest delineate the concerto’s four, continuous movements.

Beneath the concerto’s flat timeline, looking like a cutaway view of subterranean vaults, are four columns of written instructions as well as tempo and dynamic markings. The overall image is of a vibrant, colorful city bursting with possibilities.

The concerto grew out of an invitation Thomas received from William G. Brown, a life trustee of the Chicago Symphony, who had commissioned two of her previous works. The Boston Symphony has performed several works by Thomas, who taught for many summers at the Tanglewood Music Center. (She was director of Tanglewood’s Festival of Contemporary Music in 2009.)

Eschenbach has had a long relationship with Thomas, first meeting her in Chicago during his guest appearances with the CSO. (Thomas makes her home in Chicago, where she is completing her second year as the University Professor of Composition at the University of Chicago’s Department of Music and the College.)

Thomas had never worked with Harrell, so she immersed herself in his recordings and videos as she worked on the concerto.

“I was thinking of Lynn Harrell as I wrote,” said Thomas. “I was really listening to his sound—the kind of muscle, the athleticism, the intense stomach and power and joy of sound that he brings. He’s a big, joyous player.”

When the concerto was finished, she flew to Los Angeles to go over the score with the cellist at his home in Santa Monica.

“We were sitting at the dining table, flipping through the pages and playing some of it at his piano,” said Thomas. “This was a month before the due date. I wanted Lynn to have time, if there was something he didn’t like, to tell me so that I could get it all done.” According to Thomas, Harrell told her, “Don’t change a note.’’

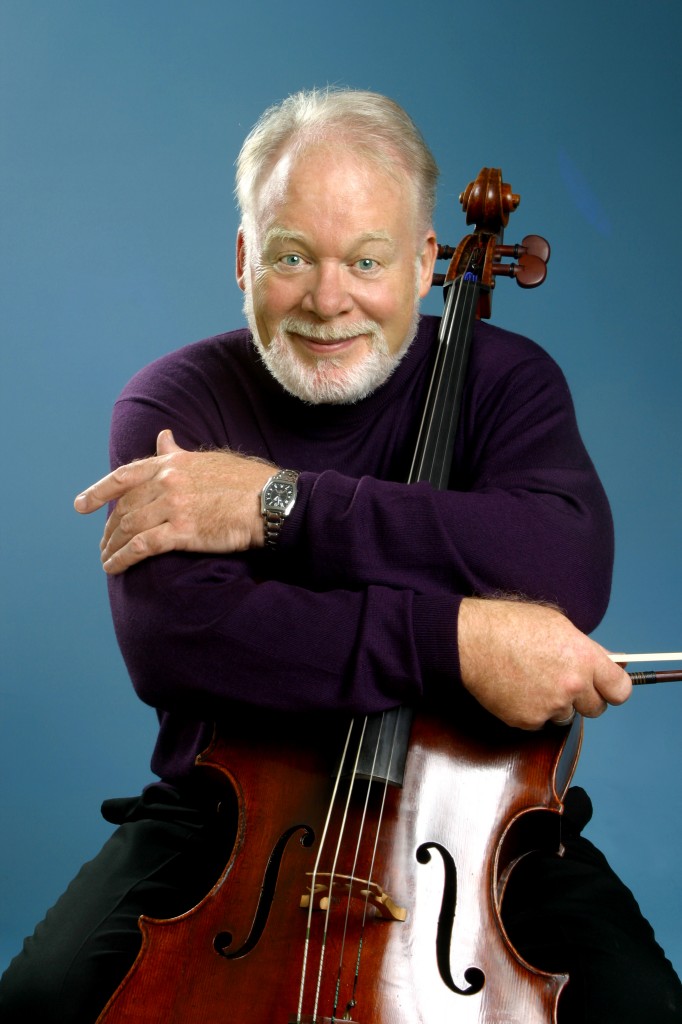

Lynn Harrell Photo: Christian Steiner

Along with the finished concerto, she took along four visual art sketches, one for each movement. (Though each movement is distinct—progressing from moderate to fast to dreamy to playful—there are no breaks between movements.)

“As we read through the score together,” she said, “I was able to quickly situate him in the overall form, flow and context. It was useful in our meeting.”

“I’d heard her earlier chamber cello concerto,” said Harrell, “but I met her only after we agreed to have this commission.” Looking at some of Thomas’ earlier work, he said, “I was fascinated with the musical language and the harmony, and the individuality of her personality. The music really sounds like her music.”

Thomas, who was born in Glen Cove, N.Y., studied piano and trumpet before settling on composition, but she has developed a strong affinity for string instruments.

“We saw so much eye to eye about the capacity of the cello,” Harrell said. “It’s very sweet to meet someone who has a [grasp] of what the cello can do in completely new ways but also being faithful to its intrinsic nature.

“There are frequent rests for the cello, for example, in this concerto. Most cello music has long sections where the sound is constantly happening. Augusta breaks this up so that we feel breath, we feel stuttering or speaking quickly, staccato-like.

“It adds to the panorama of what the cello’s nature is,” he said. “She understands that the cello is an instrument that’s always directly related to our voice. It never goes arbitrarily way higher than the voice as a violin does.”

Though Thomas’ works carry vivid titles, she doesn’t always start with a precise title in mind. Legend of the Phoenix grew out of the concerto’s content rather than vice versa.

“The music is so hot in my brain,” said Thomas, “that that is ultra-primary. But usually I do have an image or some kind of internal drama in my mind. Maybe there’s an inner momentum, [a sense] that the piece is going somewhere and that it’s going to traverse different sections for instance.

“This piece is extremely colorful,” she said, “very optimistic, full of sunshine. It’s clean; it’s not big mud puddles of orchestration. The overall affect is very positive, and so the idea of something [like a phoenix] rising out of the ashes seems very positive. Things keep re-emerging and re-building and re-sounding. And I like the image of fire–sparkling like a sparkler, stars in the night. Lynn thought this was the perfect title for what the piece sounds like.”

Eschenbach recalls his first encounter with Thomas in Chicago. “She showed me some of her works,’’ said Eschenbach, “and I liked very much her uncompromised personality. She’s a virtuoso in writing for the orchestra. In the cello concerto, the writing is extremely lucid. It’s very fiery, with high, long notes in the cello that fly over the orchestra. There’s a great sense of lyricism and of drama. There’s much drama in the cello concerto. And humor also, and a wistful element.

“It is,” he said with a chuckle, “a typical gusty Thomas piece.’’

Lynn Harrell, Christoph Eschenbach and the Boston Symphony Orchestra present the world premiere of Augusta Read Thomas’s Cello Concerto No. 3, Legend of the Phoenix 8 p.m. Thursday, 1:30 p.m. Friday and 8 p.m. Saturday at Symphony Hall. The program also includes Mozart’s Symphony No. 41 (“Jupiter”) and Saint-Saens Symphony No. 3 (“Organ”). bso.org; 888-266-1200.

Wynne Delacoma was the classical music critic for the Chicago Sun-Times from 1991 to 2006. She is a regular contributor to Chicago Classical Review, and continues to write for the Sun-Times, Musical America.com and other outlets. Since 1982 she has been an adjunct faculty member at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism teaching arts reporting and criticism as well as general reporting.

Posted Mar 14, 2013 at 10:37 pm by lajos

I just had the misfortune of hearing this piece at the BSO. It was torture. Awful. I don’t think there are words to describe just how bad it was. My head still hurts. I spoke with many people during the intermission, nobody had anything good to say about it.

If the CIA needs new torture music for terrorists, look no further.