“X” fires Met stage with compelling character portrait, colorful staging

The existence of a compelling opera about Malcolm X by the Davises—composer Anthony, librettist Thulani, and story author Christopher—has been no secret for four decades. But the urgency to hear it is something new.

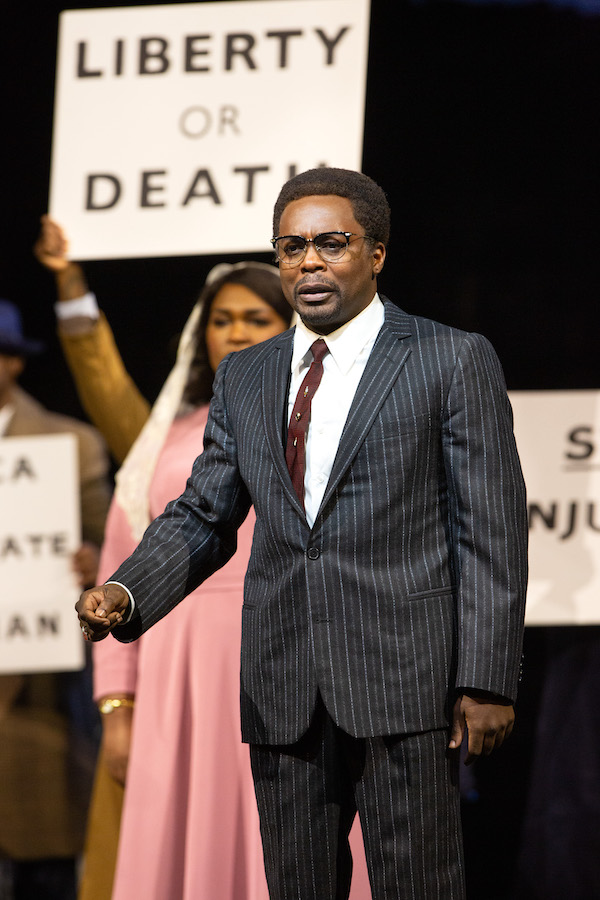

The Metropolitan Opera answered that urgency Friday night with a spectacular new production by Robert O’Hara of X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X. For all its technical wizardry, whirling projections and stagefuls of dancers, the staging kept the focus squarely on the inner journey of its iconic protagonist and his message to black Americans.

This company premiere, billed as from a “newly revised” score, followed a regrettably sparse history of X productions beginning with a staged “pre-debut” in Philadelphia in 1985 and the official world premiere at New York City Opera in September 1986. There have also been well-received mountings in Oakland and Detroit, the latter led by Friday’s conductor, Kazem Abdullah.

Older members of the audience remember well the fear and loathing that the Nation of Islam, and its most prominent minister, inspired in white America during the early 1960s. And yet the public’s fascination with this inconvenient truth-teller was such that his 1965 autobiography, co-authored with Alex Haley, became a bestseller, and was soon recognized as a fundamental text of American history.

Malcolm X’s place in the public imagination inspired the Met’s opening tableau: Dispensing with the conductor’s customary entrance to applause, the house lights simply went down, the orchestra rumbled, and the curtain rose on Will Liverman in the title role, standing with his back to the audience in a beam of light emanating from a giant donut-shaped object like the spaceship in Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

That donut became the production’s projection screen, dancing with vintage photos, news headlines, and African-style abstract graphics as the scene demanded, all created by Yee Eun Nam—who, like all the other production designers mentioned below, was making her Met debut.

Beginning with that tableau, Clint Ramos’s single set did yeoman duty in conveying the opera’s many meanings and associations. As counterpoint to the futuristic donut (echoing the Guggenheim Museum and 60s modernism), a tiny, antique mini-stage, framed in gold with a plush red curtain, served as the locus for the opera’s domestic scenes and formal temple gatherings.

Far from spectacle for spectacle’s sake, these production elements were at the service of Christopher Davis’s story—and yes, even this famously-documented life needed a sort of theatrical Alex Haley to focus its message onstage. Rather than march through it year by year, Davis, the composer’s brother, selected a series of turning points in a life full of them, showing how each shaped the character and self-awareness of one man who was simultaneously a seeker and a leader.

The result was less a “life and times” in the conventional sense than an intimate portrait against a backdrop of momentous events. The libretto by Thulani Davis, the composer’s sister, imagined dialogue at home between the boy Malcolm and his mother, created the slick lowlife character Street to stand for the urban underworld and its temptations for an adolescent Malcolm, and drew liberally on Malcolm’s own hard-hitting words as a public figure and his meditations as a spiritual aspirant.

Composer Anthony Davis has cited Wagner and Berg as influences, as well as a variety of drumming rhythms from around the world. One was aware of the former in the score’s contemporary but very approachable harmonies, but in scene after scene it was the beat—leisurely or jumpy, smooth or syncopated—that told the story.

Davis’s lean and telling scoring, enhanced by written or improvised contributions from his eight-piece jazz ensemble Episteme, was vividly realized by conductor Abdullah, a longtime Met musical associate whose company podium appearances go back to 2009.

As Malcolm, baritone Liverman proved a fine actor, in touch with the crosscurrents of the leader’s character, and vocally up to the demanding role, if briefly outshone by the massive bass-baritone of Michael Sumuel as Malcolm’s brother (and Nation of Islam follower) Reginald.

Physically, Liverman could have used a posture coach to help him more convincingly impersonate the famously tall, ramrod-straight leader. He had little help from the staging to get his head above his listeners onstage, until what was apparently a standard-issue retail-store stepladder was wheeled in for him to stand on, at a high elevation that only emphasized his short stature.

The production’s two female leads were the vocal standouts of the night. Soprano Leah Hawkins in the crucial roles of Malcolm’s mother Louise and wife Betty briefly but touchingly enacted Louise’s breakdown at the death of her husband in Act I, and shone in Betty’s fearful aria in Act III, the evening’s most vocally operatic moment.

Mezzo-soprano Raehann Bryce-Davis provided rich-toned support to Malcolm in the roles of his half-sister Ella and the Queen Mother of the Temple of Islam.

Tenor Victor Ryan Robertson was a smooth operator vocally and physically as the seductive crook Street, and later a model of imperious dignity as the Nation of Islam leader, Elijah Muhammad, deftly handling the latter role’s stratospheric tessitura.

Fine performances up and down the cast list included Edwin Jhamaal Davis as a preacher for the Marcus Garvey movement, Bryce Christian Thompson as a clear-voiced boy Malcolm, and Tracy Cox in her Met debut as an intrusive social worker and later a reporter.

Donald Palumbo’s Met chorus was kept busy indeed, and always characterful, as the human backdrop in nearly every scene of Malcolm’s paradoxically lonely journey.

Choreographer Rickey Tripp expertly staged street and bar scenes, and set a troupe of African-inspired dancers in motion as a counterpoint to Malcolm’s black-nationalist rhetoric.

Costume designer Dede Ayite and wig designer Mia Neal not only captured the look and feel of different American decades and social classes, but dressed prisoners, Muslim pilgrims, and Nation of Islam troops appropriately. The extravagant gowns and headdresses of some of Malcolm’s followers apparently symbolized the “nation of kings of Mali” referenced in his speeches, an eye-popping highlight of a visually rich production.

X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X runs through December 2. Met Live in HD in cinemas Nov. 18. metopera.org