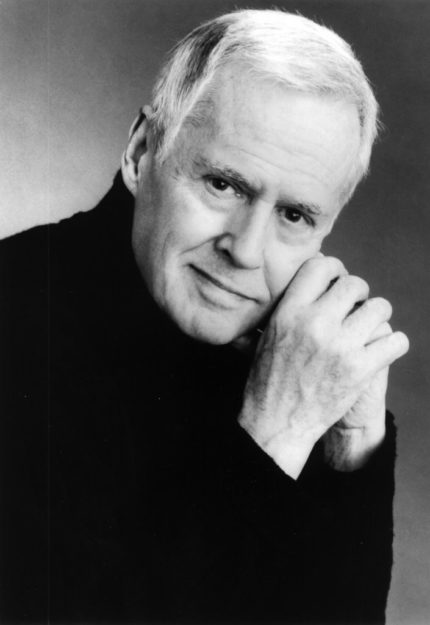

Remembering the renowned American composer and diarist Ned Rorem

News of the passing of Ned Rorem—the prolific American composer and famed diarist who died at age 99 at his home on the Upper West Side of New York on November 18—sent me back to our first meeting.

It was a steamy summer day in Ohio, in 1976, only weeks after he had been awarded the Pulitzer Prize for music—the highest award a classical musician can receive—for his orchestral suite Air Music.

I was then in my fifth year as music and dance critic of the Akron Beacon Journal. I had arranged to speak to Rorem for a profile I was writing for the newspaper’s Sunday magazine. He had come to town for the premiere of his song cycle Serenade on Five English Poems, a commission for the American Bicentennial, like Air Music.

There he was—tall, blue-eyed, matinee-idol handsome at 52—a distinguished American man of music and letters who had once traveled in the most soigné Parisian artistic circles with some of Europe’s most distinguished cultural figures, sitting down for an interview over a cheeseburger and fries at a diner in downtown Akron.

Nobody walked over to the booth to ask Rorem for his autograph, as they would a football hero who had just been awarded the Heisman Trophy. In fact nobody appeared to recognize him at all. One of America’s foremost composers was just another customer grabbing a quick bite.

Rorem came across as an artist of disarming candor, fierce intelligence, urbane wit and, above all, enormous personal charm. We hit it off immediately and, despite the professional boundaries that separate creative artists and critics, became friends.

By the time of our first encounter, he had written hundreds of art songs, the genre on which his reputation as a composer chiefly rests to this day, along with a raft of orchestral, instrumental, choral and chamber music.

A decade had passed since the publication of The Paris Diary of Ned Rorem (1966), the first in a long series of candid, revealing, compulsively readable Rorem journals, scandalized the literary world with its indiscreet accounting of the young composer’s carnal exploits in the City of Lights during the ‘50s.

His openness about his homosexuality in fact made him a hero for the pre-Stonewall gay movement as among the first well-known artists to come out of the closet, without fuss or fanfare.

Following my move to the Chicago Tribune, Rorem and I kept in touch, off and on, for some 25 years. We were bound by mutual respect, a predilection for naughty gossip and a kind of journalistic synergy: I gave him media exposure, he gave me good copy.

I was among his guests at a few soirees he hosted in the tidy, art-filled Manhattan apartment he shared for 32 years with his partner, James Holmes, an organist and choir director, who died in 1999. Rorem enjoyed holding court and he did so like a latter-day Gertrude Stein, dispensing wit, wisdom and advertisements for himself with equal elan.

You never quite knew whether you would get lofty pronouncements about The State of Things Cultural, recitations of his health woes or grumblings about mundane domestic matters. (Or all three.) Once, over herbal tea and raspberry tarts, he complained at length about the “racket” emanating from a giant air conditioning unit atop a building adjacent to his residence on West 70th Street. He said he had “bitched up a storm” about the noise to the unit’s owner, Itzhak Perlman, to no avail.

We also met when local performances of his pieces brought him back to his beloved Chicago.

Chicago was the culturally alluring metropolis where the Midwest-Quaker-reared native of Richmond, Ind., had grown up, where his first piano teacher introduced him to the music of Debussy and Ravel, and where, at age nine, he wrote his first songs. Every return to the city was a sentimental homecoming—an occasion to rekindle old friendships, to reflect on what first inspired him to set music and words to paper.

Despite Rorem’s many successes, particularly those in the post-Pulitzer chapter of his career, and the worldwide fame he came to achieve, his self-admitted inferiority complex made him ever distrustful of a musical establishment that had long treated his elegantly lyrical, neo-romantic music with malign neglect.

That music, while peppered with mild dissonances and sometimes pungent chromaticism, is couched in an accessible idiom that remained essentially unchanged from the day when Rorem and other tonal composers pitted themselves against the atonal hard-liners of the Boulez-Carter brigade—the “serial killers,” as he famously called them—who dominated classical music composition in the postwar decades.

He paid close mind to what was written about his music, all the while pretending indifference to reviews. Whenever he knew of my having covered a performance of one of his works, I would almost invariably receive a handwritten postcard of implicit thanks, signed “Eternally, Ned”.

Rorem always considered himself “a composer who also writes, not a writer who also composes.” Even so, the 15 diaries and books of critical essays he published over the course of roughly three decades brought him to a larger audience than his music.

Dip down anywhere in these volumes—filled with trenchant cultural criticism, philosophical musings, entertaining anecdotes and wicked wit—and you are certain to find choice aperçus and pithy observations. For example:

“The twelve-toners behave as if music should be seen and not heard.”

“With Debussy you get what you pay for. With Mahler you get more than you pay for.”

“Twyla Tharp’s rag-doll, loose-limbed choreography is all about charm, while she herself has none. Conversely, Elliott Carter, the man, drips with charm, while his work has none.”

Yet it was in the medium of art song, of which Rorem wrote more than 500, that he excelled, to an extent no other American composer has equaled or surpassed, either in quantity or quality.

In a recent tribute, a New York Times critic wrote that “you would be hard-pressed to find greatness in Mr. Rorem’s vast oeuvre.”

I could not disagree more strongly.

Start with any number of his art songs, such as the early pieces “Early One Morning,” “The Lordly Hudson” and “Little Elegy,” exquisitely crafted miniatures that seduce the ear with their elegant lyrical beauty. Rorem’s melodies, with their graceful linear flow, turn words into enhanced speech.

From there, turn to later masterpieces such as Evidence of Things Not Seen (1998), his magnum opus, an evening-length song cycle for four voices and piano that draws on 36 disparate texts to create a wondrous vocal tapestry.

Rorem the Quaker pacifist rears his head in the powerful declamation of the cycle War Scenes (1969), five settings of excerpts from the Civil War diaries of Walt Whitman, dedicated to the casualties of the Vietnam War.

There are also gems in Rorem’s orchestral output, such as his String Symphony (1985), Sunday Morning (1977) and Third Symphony (1958)—clear, well-honed, eminently accessible translations of his vocal idiom into a large-scale symphonic framework.

Nor should one neglect such prime instrumental works as the Piano Sonata No. 2 (1950), thoroughly French in sensibility, and the Concerto for Piano Left Hand (1991), a deftly wrought showpiece that takes up where Ravel left off 60 years earlier.

The last time I spoke with Ned Rorem was by phone in 2002, on the eve of the world premiere, at Ravinia, of his song cycle, Aftermath, a song cycle for baritone, violin, cello and piano with texts (spanning Shakespeare to Randall Jarrell), inspired by the terrorist attacks of 9/11. It remains one of his most personal and deeply felt works, summing up the “quizzical melancholy” that seemed to consume him in the winter of his life.

But even when American music’s onetime enfant terrible-turned-elder statesman was sifting through the tea leaves of his mortality–wondering how much time he had left (actually he had 20 more years)–he found room for typically quotable hyperbole.

“I think American society has got ten more years to go, and then we’re gonna blow ourselves up,” Rorem lamented. “If we don’t, we will be one big mediocre family eating at McDonald’s…”

Or at a greasy spoon in Akron.

John von Rhein was the classical music critic of the Chicago Tribune for four decades. He retired from the paper in 2018.