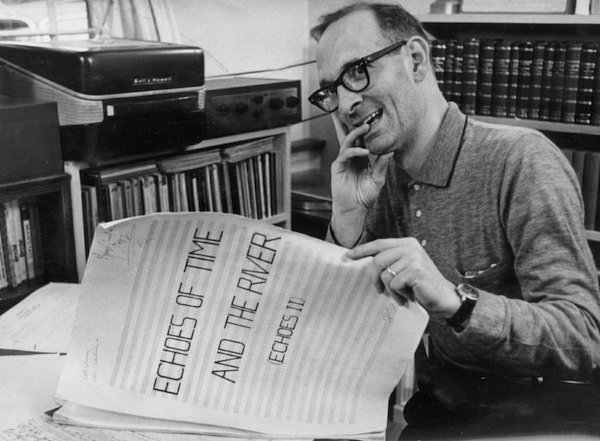

George Crumb 1929-2022

George Crumb, a composer whose music connected the long tradition of classical music to the post-WWII avant-garde and to global culture, drawing in listeners outside the classical world, died on Sunday at the age of 92. Bridge Records, which has produced a 20-volume recorded edition of his works, under the composer’s supervision, made the announcement.

Crumb was part of a unique generation of American composers who rejected the mid-20th century atonal orthodoxy and built a new compositional language on often ancient traditions but expressed via a contemporary aesthetic—often using amplification and recording technology as equal parts in the instrumentation. The constant adaptation of new means to long-standing ideas was a main reason for Crumb’s music emerging as grounded in tradition yet refreshing beguiling, and wholly original.

The sound of his most prominent masterpieces, Ancient Voices of Children, Makrokosmos, and Black Angels remains unique. Written with meticulous care and exacting clarity, his works often have an extra-musical drama that enhances their depth and broadens their appeal. From the inside, that drama comes from the visual appeal of his scores, which might have staves hand-drawn into curves, spirals, and peace signs, giving the musicians an evocative flow of his notation through time. For the audience, works like Vox Balaenae and Black Angels called for specific stage design and lighting, and even masks, adding a ceremonial and ritualistic expression to the music itself.

Those works also included important timbral features—Vox Balaenae was inspired by hearing recordings of whale song—especially amplification. Black Angels (1971) is composed for an amplified string quartet, and the musicians not only use their bows in unconventional ways but also play percussion instruments and water glasses at various stations on the stage. It is by far Crumb’s most famous work, and one of the most important and striking compositions of the 20th century. Written in response to the Vietnam War (it is dedicated “Friday the Thirteenth, March 1970 (in tempore belli)”), it is full of outrage and abrading emotions, yet is always free-flowing and musical.

Early responses to this and other works at times accused Crumb of merely reaching for effect, but there was a musical purpose (not only expressive but structural) behind every means. Not the least of these was an uncanny, gripping beauty that both unsettled the ear and drew it further into the experience. The opening “Night of the Electric Insects” was used in the soundtrack to The Exorcist, bringing Crumb to a mesmerized mass audience. The Kronos Quartet has made it a staple of their repertoire.

George Crumb was born in West Virginia in 1929. Both his parents were musicians, and Crumb’s clarinetist father taught him the instrument. He was one of the first major composers to grow up in the world of radio and sound recordings, and that meant his world included pop and American vernacular, along with classical.

As he told an interviewer in the late 1980s, “I think composers are everything they’ve ever experienced, everything they’ve ever read, all the music they’ve ever heard. All these things come together in odd combinations in their psyche, where they choose and make forms from all their memories and their imaginings.” Crumb also told guitarist David Starobin, one of his most important interpreters, that he heard non-Western music through the Smithsonian Folkways Series of albums. Through these, he would have heard the musical saw, which he remembered from West Virginia, in the traditional music of other cultures. He would later use it in Ancient Voices of Children.

Crumb earned a bachelor’s degree from the Mason College of Music in 1950, and then a master’s degree in 1952 from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. His doctorate followed seven years later, from the University of Michigan, and he himself taught, first at the University of Colorado and then most prominently at the University of Pennsylvania, from 1965 to 1995. (One of his children, David Crumb, is also a composer who teaches at the University of Oregon).

His music is full of the intuitive pleasures of listening and responding emotionally and physically before any consideration of structural and formal design. That value in the pure pleasures of sound is inherent to the way his work appeals to such varied listeners. While one can hear Medieval structures and bits of Bach and Schubert in his music, Crumb didn’t try to outline history, or make music that worked as an abstract structure. His art was expression, response, emotion, and beauty, the qualities of pure sound and timbre that touch people. In this sense Crumb spent decades going for effect, creating sounds and giving them enough space so that something would happen inside the listener. That is the effect all music strives for, and Crumb was a master at it.

The one history he did create was that of the floating world of global music, available through modern technology. As he wrote in a 1980 article titled “Music: Does it Have a Future?” in the Kenyon Review, “the total musical culture of Planet Earth is ‘coming together’… An American or European composer…now has access to the music of various Asian, African, and South American cultures. …This awareness of music…as a worldwide phenomenon…will inevitably have enormous consequences for the music of the future.”