As Thomas Sleeper battles a major illness, his reputation as teacher, conductor and composer endures

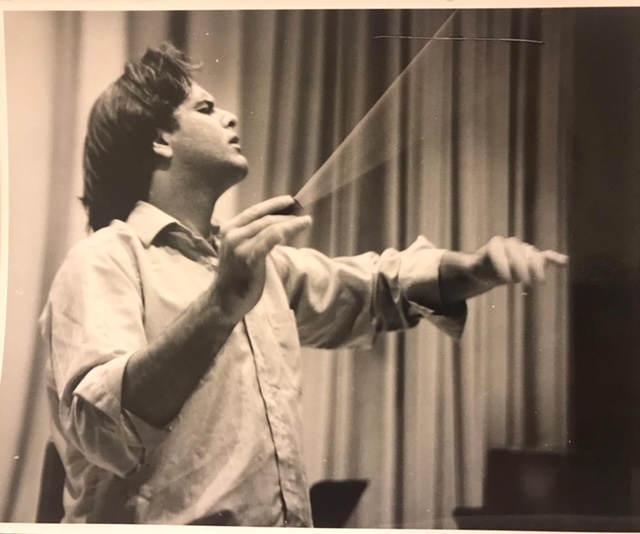

The conductor Thomas Sleeper stood before the University of Miami’s student orchestra and prepared to lead them in what any informed observer would consider a likely train wreck.

They were about to perform Richard Strauss’s Don Juan. A ferociously difficult work, Strauss’s tone poem is a perennial audition piece for professional orchestras, with aspiring applicants required to make solo runs of its Allegro molto gantlet of triplets and sixteenth notes.

Even though he was leading students, Sleeper demanded they play it at full speed, and as it turned out, there was no train wreck. They nailed Strauss’ runs and figurations. There’s no need to get carried away, and no one would have mistaken them for the Boston Symphony Orchestra. But the young musicians brought off the 2012 performance with real Straussian sheen and swagger.

As a composer, Sleeper has produced operas, concertos and symphonies, a huge body of work that has been favorably received by critics. As a conductor, he had the singular honor of leading the belated Chinese premieres of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony and Brahms’ Piano Concerto No. 2.

But the Oklahoma-born bass trombone player has made his biggest mark in South Florida as a master teacher and conductor for the University of Miami’s Frost School of Music (from 1993-2018), with an uncanny ability to demand the best from his students without bullying them.

“You couldn’t meet a finer man, but he has high standards, and everybody knows it,” said William Hipp, retired dean of UM’s Frost School of Music, who hired Sleeper. “He doesn’t get in their face. Everybody I know loves Thom Sleeper.”

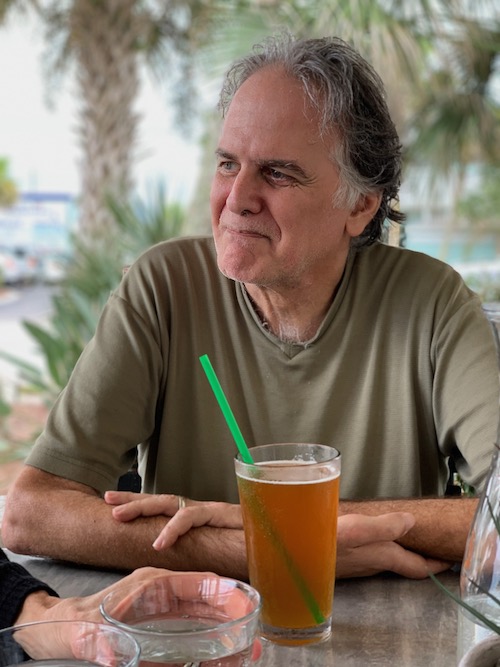

An imposing man with the long, swept-back hair of a 19th century Romantic composer, Sleeper, 65, is now suffering from ALS (Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis). Long known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, ALS is an incurable illness that causes the progressive loss of nerve control of the muscles. He speaks more slowly than he used to, taking time to gather his words. As he and his wife Sherri have coped with his condition, messages of support flowed in from across the country from the vast network of students whose careers he influenced.

“He’s a huge man who loves his work, loves his students, loves his family,” said Zoe Zeniodi, a former star conducting student. “He’s a man who works for his students, works for his children to make the world better after him.”

Sleeper, who was diagnosed in April of 2019, is handling his illness with a level of class and fortitude that would surprise no one who knows him.

“He’s more courageous than you can imagine a person being,” said his wife, the visual artist Sherri Tan. “He’s quiet. He works hard at what he’s supposed to work hard at and he keeps going. He does not complain.”

Although he isn’t composing, he responds to requests for copies of his music from musicians who want to perform it. He does physical therapy and respiratory therapy. And because he rarely says anything about how he feels, his wife has to ask him.

“Getting through the day is extremely taxing,” she said. “To get through the day is a lot of work, something that takes up every bit of energy. But he is not a complainer. He just does what needs to be done.”

He has influenced countless students. When Zeniodi came to the University of Miami, she intended to study piano. But he spotted talent she didn’t know she had and persuaded her to switch to conducting.

At first, she refused.

“I’m a woman. I come from Greece and women don’t become conductors,” she told him.

“You can,” she recalled him saying. “You’re in the U.S.A.”

Conducting classes took place largely in silence. Zeniodi would stand in his office and lead an imaginary orchestra in Beethoven or Mozart or Stravinsky. The point was to maintain a firm vision in her head of how she wanted the work to sound and impose that on the orchestra, rather than to passively ride on the sounds any competent orchestra could produce.

“He would stop me in the fourth bar and say you didn’t hear the violas here. And I’m like, ‘How the hell did you know?’ And he’s like “Because I could see that. I know what you hear.’”

Like the winning football coach all the players hate, excellent conductors can be tyrants (see Arturo Toscanini). But Sleeper is not. He achieves his results largely through the inspiration he gives musicians, a dedication to his art and a composer’s knowledge of the instruments of the orchestra.

“The way he connects with the musicians is really what separates him as a conductor,” said Sage McBride, a talented young violinist who would go on to study in New York with Pinchas Zukerman.

“Some conductors are just super harsh and it’s not very inspiring. He really knows how to inspire the musicians and bring the best out of them. I was just so inspired by him after every rehearsal I would just go and practice to be an even better musician than I was.”

As a violinist in the Florida Youth Orchestra, McBride played under Sleeper for years. His most memorable experience was a performance of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony in a side-by-side concert of his youth orchestra with the University of Miami’s Frost Symphony Orchestra.

“The way he works with the kids to bring them to such a high level of artistry is really amazing,” he said. “I owe a lot to Mr. Sleeper for the musician I am today, both for internal artistry but also as an orchestral musician.”

At the University of Miami, Sleeper’s primary goal was to give the young musicians a well-rounded education in orchestral music. “Thom always has in mind a four-year curriculum, so by the time they graduate they will have covered a certain amount of repertory,” Hipp said. “He doesn’t repeat the same works, but a breadth of style, periods and composers.”

Sleeper’s success with the orchestra comes both from his knowledge of the music and his personal style. “When he gets on the podium, he knows every aspect of the score in front of him, and he’s able to communicate the essence of that to members of the orchestra,” Hipp said. “He’s not intimidating in style. He’s reinforcing the players’ best efforts to render the highest level of performance of which they’re capable. He has everybody play above their heads, in other words.”

Asked how he drew such results from a student orchestra, Sleeper gives a technical answer that reflects a man who doesn’t let a single note or rest pass without thought.

“I would do sectionals, just for winds, just brass, just violins,” he said. “You can balance the section within itself. Make sure the sound isn’t just coming from the front row. Make sure it’s in tune and the rhythms are the same.”

“They start together, take rests together, approach the rest the same way. Sometimes you need to crawl to the rest, sometimes you take the rest, sometimes you need to calm the sound down to the rest. It depends on the music.”

He motivated the students to broaden their perspectives beyond their own parts. He allows sections of the orchestra to critique each other, asking the brass, for example, what they thought of a passage in the cellos. He allows students to try their hands at conducting.

He sprinkled top players throughout the strings, rather than engaging in the weird and petty ranking common in orchestras that clusters the best players toward the front. At concerts, he asks everyone to stand who had something to do with performance, teachers, administrators and support staff.

But with this generosity of spirit comes an insistence on high standards. Sleeper recalls his own audition for UM, when he stood before the student orchestra. A woman in the back raised her hand and asked about his grading policy.

“It’s easy,” he told them. “You show up to every rehearsal and concert, you get an A. Miss one, you get a B. Three, you get a C. Four, you get a D and you fail.”

As a teenager, Sleeper listened to rock and jazz and played the trombone (“The only instrument you can play with your fists,” he observed).

“When I was that age, I thought Brahms was a wimp,” he recalled in a 2001 interview. “He would never get to the point. Give me a climax quickly in a two-minute piece. But I grew up eventually to appreciate the finer arts.”

He studied at Southern Methodist University, where the local conducting eminence gave him an early example of the teacher he didn’t want to be.

“The one lesson was him sitting there at home drinking scotch and yapping at me about his life,” he said. “That was the whole lesson.”

Sleeper’s own approach to teaching conducting involved no scotch and took place largely in silence. But his methods worked.

Zeniodi’s conducting career, which wouldn’t have existed if she hadn’t met him, would take her to the podium of Florida Grand Opera, to Carnegie Hall where she led the New England Symphonic Ensemble and to the podiums of orchestras across Europe, Asia and the Americas.

“I owe him my life,” she said. “He is the most generous human being I have met,” she said. “He could be harsh. He’s not a soft person who will be sweet and who will accept things. No. But he’s the most giving, direct and honest, with a total sense of integrity.”

(David Fleshler)

________________

The Music of Thomas Sleeper

Thomas Sleeper’s immense contribution as conductor and educator for twenty-five years at the University of Miami’s Frost School of Music has tended to over shadow the depth and variety of his work as a creative artist.

Sleeper’s compositional output is prolific and remarkably diverse. Adhering to no single stylistic agenda or trend, Sleeper’s works reflect his vast performing experience in their fluency of instrumental and vocal writing. Often his scores have brought fresh life to such time-tested musical forms as the symphony, concerto or song cycle.

Sleeper’s early works tended toward musical expression that was dark and angst-ridden while more recent pieces burst forth with a sense of optimism. His instrumental lines ring with conviction and he has repeatedly created works that display the performers at their best while remaining ingratiating to the listener. Often written for fellow Frost faculty members, Sleeper’s compositions consistently revel in the sheer command of the player’s instrument and display an eagerness to share that sense of wonder and excitement with audiences.

For Frost Wind Ensemble conductor Gary Green’s valedictory performance in 2015, Sleeper created a masterful Chamber Symphony that brims with neo-classical invention and graceful instrumental felicities. His Violin Concerto (“Hypnagogia”), written for violinist Huifang Chen in 2012, is both rhapsodic and terse, a virtuoso display piece in the great tradition of mid-20th century concertos for the instrument. (Chen and Sleeper have recorded this superb score.) Sleeper’s song cycles Xenia (2010) and Through a Glass Darkly (2011) traverse Berg-ian arioso and sprechstimme in moody thematic patterns.

The hard-edged astringency of the Concerto for Alto Saxophone (2010) and the exuberance of the Horn Concerto (2000) and Trumpet Concerto (2003), available on recordings and Youtube, reflect Sleeper’s enthusiasm for creating works for instruments that lack a large solo repertoire. The vast Adagio slow movement in Sleeper’s Symphony No. 1 is Mahlerian in scope and pathos. In the opera Alcedama, Sleeper took the Biblical tale of Cain and Abel and traced it through the centuries to the Holocaust and modern day civil conflicts with music deeply searing in its emotive impact. (Sleeper has recorded the work on Albany records with a cast that includes Russell Thomas and Sandra Lopez, Miamians who have sung to acclaim at the Met and internationally.)

Sleeper’s output also has a lighter side. What other composer would conceive a Concerto for Flute and Flute Ensemble? Sleeper’s 2012 gift to former Metropolitan Opera principal flute Trudy Kane and her students abounds in kaleidoscopic colors and shifting moods. Leylie’s Dance, celebrating his daughter, abounds in the insouciance of Satie. The Sapphire Overture (also known as Hana’s Day Out) suggests Leonard Bernstein in his high-stepping Broadway mode. Even the psychological drama of the brief operatic vignette The Sisters Antipodes is cast in the flowing melodic strains as well as cynicism of early Stephen Sondheim (a la Company and Follies). The jazzy finale of the Suite for Baritone Saxophone is quintessential Americana.

Sleeper’s music can be accessed on his website, sleepermusic.com. Also a search in the SFCR archive will bring up reviews of his works, many in their premieres.

Thomas Sleeper’s output has greatly enriched the solo instrumental, vocal and ensemble repertoire. The energy, vibrant theatricality and depth of feeling in his scores will continue to resound on concert stages and recordings with their consistent sincerity and vibrancy of musical expression.

(Lawrence Budmen)