Kentridge’s “Wozzeck” paints a militarized nightmare in Met premiere

Alban Berg’s opera Wozzeck is a misfit in the canonic repertoire. It is one of the finest opera scores made but is so particular to a style from a specific era—Expressionism—and so downbeat, that it both contravenes the grand opera tradition of the major houses and exists at a distance from the kind of sympathetic personal experience one can safely find in Verdi, Mozart, and the like.

Productions, more than the work itself, are responsible for the latter. The weirdness of Expressionism and the main character, a simple-minded soldier driven to insanity and murder, are hard to connect to contemporary audiences, and stagings often come off as taking place behind glass, observed but not felt. The frustration is that Wozzeck has an explosive device at its center, sitting in plain sight.

William Kentridge’s new production, which opened Friday at the Metropolitan Opera, has lit the fuse and burst open any artifice or phoniness.

This staging, with the great baritone Peter Mattei in the lead role, presents the ugliness that Berg saw during his WWI experience and translated through his score. Wozzeck is not the usual kind of pleasure; it is beautifully made but not beautiful—honest and sincere about ugly and upsetting things, it shows people in extremis without making their anguish into something musically glorious.

Supported by the Met, the Salzburg Festival, the Canadian Opera Company, and Opera Australia, this Wozzeck creates a world that is unstable and chaotic. The program notes specify that Kentridge (who brought new productions of Berg’s Lulu and Shostakovich’s The Nose to the Met) decided to set it in pre-WWI Germany. There is in that milieu an atmosphere of a society coming to its end, of atavistic impulses and decadent meaninglessness coming through the characters. Berg wrote this into the music, and tenor Gerhard Siegel, bass-baritone Christian Van Horn, and tenor Christopher Ventris as the Captain, Doctor, and Drum Major respectively brought it to life in their full-bodied performances.

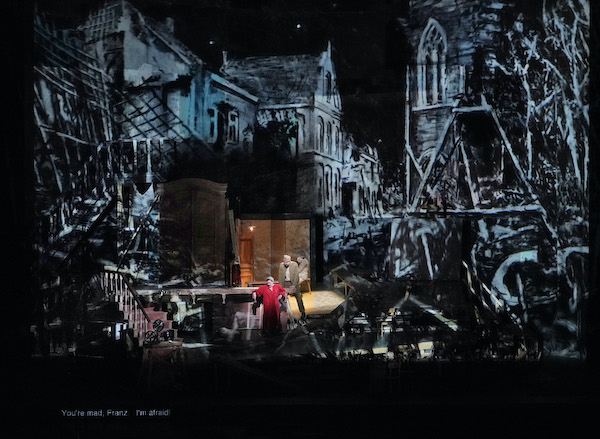

But the staging is tied specifically to WWI itself. There are images of maimed soldiers, barbed wire, gas masks, and in Act III a battle map projected over the stage that shows Ypres, site of some of the worst of the war’s industrialized butchery. The set looks like it’s made out of wreckage, and rather than cutting sticks, Wozzeck and Andres (tenor Andrew Staples in his Met debut) venture out into no-man’s land to recover chairs, which litter the stage.

There is the sense that both the world will be destroyed and that, through the debris, it already is destroyed. There was a foreboding feeling from the Captain’s first “Langsam!” Siegel’s piping, unusually graceful singing was one of the expressively destabilizing factors—he had a Colonel Blimpish pomposity and a glassy-eyed madness as he sang about his terror of eternity and the world’s spinning.

Mattei was performing against type in this role. His typical easy command of the stage and the intelligence and pure beauty of his singing at first made it hard to accept him as the simple-minded soldier. Mattei is one of the most self-aware opera artists, and Wozzeck is helpless exactly because he has no self-awareness. But the Act I scene with the Doctor—sung by Van Horn with almost bouncing malevolent vitality—set in a claustrophobic shack, worked brilliantly, Mattei’s sincerity playing off the Doctor’s unhinged pseudo-rationalism.

Wozzeck was a sane man turned crazy by madmen, the madmen were all his social superiors, everything flowing downhill from them. Along with the chairs, a second key detail that Kentridge changed was that Wozzeck isn’t shaving the Captain at the start, instead he rolls a movie projector on stage and starts showing the producer’s trademark animation (projected on a small screen on stage, while large projections encompassed the entire stage). Wozzeck’s movies were the chaos of memories from the war, and one saw the character as shell-shocked, emptied out by those experiences.

Soprano Elsa van den Heever was Marie. Her shining voice was a lovely contrast to those of all the men, especially the accumulated falsetto passages that Berg gave them. She was as empty as Wozzeck, but in a different way—while forces pushed down on the soldier, they pulled Marie into their embrace. That meant Ventris’ peacocking, strutting and sinister Drum Major, and in a larger sense the world of gaudy, hollow uniforms.

In another small but radical departure from the score, Kentridge replaced Wozzeck and Marie’s son with a puppet, one that in no way could be mistaken for a human child even without the puppeteers handling it in full view. At the finale, their son and the children who discover Marie’s body sing from offstage. This change didn’t work—one felt nothing from the puppet, nor from the absence of the human performers. And it made it impossible to feel the crucial bit of human love that Wozzeck and Marie had for the boy.

Still, the overall power of the production was such that the climactic murder was still devastating. Here is where much credit belonged to conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin and the Met Orchestra. Their playing was colorful and sinuous, the conductor handling voluptuous phrasing and changes in tempo, shaping Berg’s great forms to dramatic ends. The performance grew darker and deeper with each passing measure and reached a plateau of tension in the beer garden scene in Act II, which had the grip of a nightmare. Surrounded by a crowd of people with bandages covering their facial wounds, Wozzeck was lost, confused and desperate.

From that point the denouement was intense. Although this was only the 70th performance ever at the Met, this orchestra is expert in Wozzeck, honed in the score by James Levine.Their playing covered the gamut from delicacy to serrated brutality, while all the singing was utterly clear.

At the end, with nothing but death on stage, the projection showed no-man’s land being shelled, the screen eventually covered completely by images of explosions. The last word was not the score’s “hip hop” but the destruction the world brought on itself.

Wozzeck runs through January 22. metopera.org; 212-362-6000