Music, beauty and jugglers make for a memorable night in Met’s “Akhnaten”

Akhnaten, the last opera in Philip Glass’s trilogy of science, politics, and religion, finally made it to the Metropolitan Opera Friday night. (The Met presented Satyagraha in 2011, and back in 1976 Glass and director Robert Wilson famously financed their own two-night production of Einstein on the Beach at the house).

This production by Phelim McDermott, originally made for the English National Opera and LA Opera, stars countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo as the Egyptian king who tried to institute monotheism 500 years before the Axial age, and over a thousand before the Christian Era.

The challenge that Glass’s first three operas pose is that they are dense with ideas and meaning, but light on the libretto side, with either no story (Einstein) or little in the way of sung text.

Most of the words in Akhnaten go to the king’s dead father, Amenhotep III. That role was played by Zachary James, making his Met debut. He’s a bass-baritone, which in this opera means nothing, as it’s solely a speaking part, introducing scenes and narrating parts of the story.

Akhenaten has one solo in English (the language changes depending on the nationality of the audience), a hymn to the sun god Aten in Act II. The chorus and secondary characters sing a mix of ancient Egyptian, Akkadian, and Hebrew, but mostly everyone sings either “Ha” or “Ah.” Seat-back titles are barely used because they barely have any use.

This in no way discounts character. Rather, getting to the core of singing, the human voice and body, not only makes for visceral characterization but Friday brought out some of the most affecting singing heard at the Met. Without the distraction of what the characters might be saying, one responded to what they were doing, and from the ritual choruses to the solos and small ensembles, one felt the relationship that comes from the brain’s fundamental reaction to song; a sense of community and oneness.

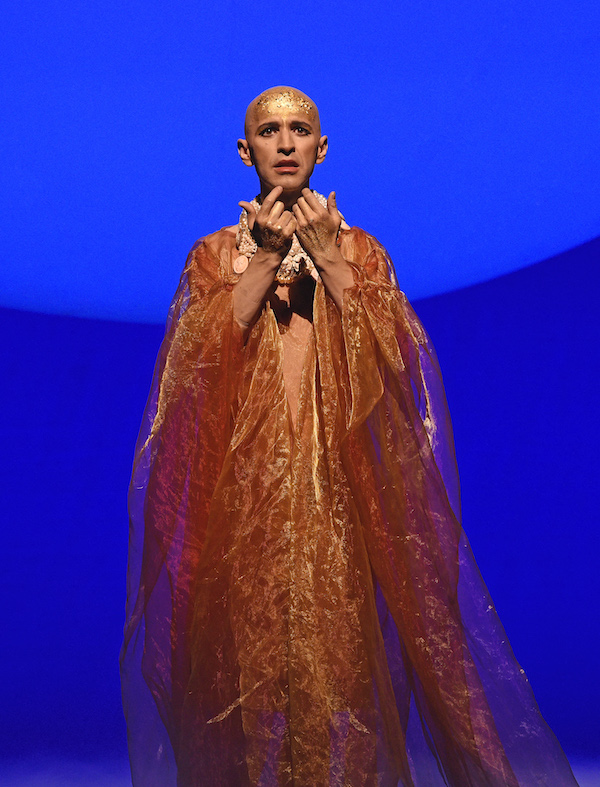

Costanzo’ s gorgeous voice could not have been more perfect. What sets him apart from other countertenors is the uncanny feminine timbre in his sound, a quality that combines the human and the otherworldly. His stage presence was tremendous. He is first seen, unwrapped from a giant cocoon, naked and hairless, but what commanded the attention was his posture, his deliberate gait, the way he held himself as he was clothed in the spectacular raiments of the god-king of Egypt.

Dísella Lárusdóttir as Queen Tye in Akhnaten. Photo: Karen Almond

The vocal blend of Costanzo’s Akhnaten with mezzo J’Nai Bridges as his wife, Nefertiti (also making her debut at the Met), and soprano Disella Lárusdóttir as his mother, Queen Tye, was sublime. Just enough alike and just enough different, they sang as individuals and spoke as one voice depending on the moment in the score.

The opera—running 3.5 hours with two intermissions—is close to nothing but music and its manifestation in physical space and time. One of the fundamental tools McDermott uses is exaggerated slow movements—fascinating in that it recalls Wilson’s technique as well, and reveals this is the most transparent, intuitive, and meaningful realization of Glass’s style.

But then there were the jugglers. On paper, the use of what was called in the program the “Skills Ensemble” might seem bizarre. But choreographed by Sean Gandini, this group was well integrated into the music. Juggling in time in itself made a dazzling three-dimensional outline of the music, and it was the juggling that was the force Akhnaten used to force out the polytheistic High Priest of Amon (tenor Aaron Blake) in Act II. These were just two surface details of the core of the juggling, which is that it was a kind of dance using arms, hands, and objects tossed in the air. And like the singing, the dance reached into the basic perceptions of the human experience.

No one in the history of opera has thought with the scope Glass has with his trilogy, not even Wagner. The duration of the Ring cycle is enormous, but what’s inside it is an extended family drama. Glass, on the other hand, is exploring the workings of the universe itself, and inside that, of human societies.

When Amenhotep proclaims, “Open are the double doors of the horizon / Unlocked are its bolts / Clouds darken the sky / The stars rain down / The constellations stagger…When they see this king / Dawning as a soul,” there was a rush of exhilaration, because that horizon is infinite. In lesser hands, Amenhotep’s lines would be portentous, but James was gripping, inside the character and narrative in both voice and body.

Supporting this infinity was exceptional craft and a sense of beauty. The way each act moves toward its climactic moment, and the way the long arc of the opera settles at its endpoint, is unsurpassed in the repertoire. Every moment points towards a special moment, every note moves the drama closer. Hearing and seeing that come to pass Friday was deeply thrilling in the mind and the body—one knew each note and step was another piece of the path, without necessarily knowing what was next. But it was clear there was a direction and purpose to everything, and one was led, gladly, into each new bit of the future.

Akhnaten is easily one of the finest things to ever appear at the Met. The intense beauty of the production was its own thrill. The magnificent costumes by Kevin Pollard have a few touches of ancient Egyptian iconography, but mainly mix Victorian era steampunk and touches of Edwardian fashions. In the second act, Akhenaten and Nefertiti affirm their love while wearing matching red gowns with trains dozens of feet long. As they sang, they entangled each with the other.

To end that same act, Akhenaten returned in a glowing, orange robe, and as he sang in honor of the sun god, he ascended a stairway to a giant, luminous globe. It was the sun itself, and it was beautiful and moving when he reached it, the apex of his life’s meaning.

Another notable debut was that of Chicagoan Karen Kamensek, conducting the singers and Met Orchestra. Glass has always composed within the classical tradition, but his personal idiom, even after all these decades, is still a challenge for ensembles that predominantly play music from the common period. His extended repetitions can be physically, and especially mentally, challenging.

Kamensek is experienced in Glass’s operas, and under her the orchestra sounded right at home. There was an excellent balance of instrumental colors—and with the singers—and the playing had focus and equipoise, the kind of warmth one can feel, and it flowed and built a profoundly affecting momentum while always held with a light and certain grip. One has never heard Glass’s music sound better than in the big house Friday night.

Akhnaten runs through December 7. metopera.org