Prepping for Beethoven 250 birthday bash: A selective CD guide

“After Beethoven,” Benjamin Britten famously wrote, “came the rot.”

He had a point.

The 19th century elevated the composer to a heroic cult figure of marbled, Olympian godliness, the sacred relic of a Romantic religion founded on works that “would live forever.” Fast-forward more than a century to a classical music performance industry fixated on what Virgil Thomson called the “50 Famous Masterpieces,” many of them Beethoven’s, all of them to be executed with ever glossier, digital-era perfection.

See what you started, Ludwig.

Well, Beethoven was one of the great musical geniuses of all time, no question about it. But, given the omnipresence of his music—in the concert hall, on recordings, TV commercials and over the Internet—is it really necessary to lionize that body of work and its creator all over again? Apparently the 250th anniversary of the German composer’s birth makes that a foregone conclusion.

With the mega-Beethoven-birthday bash upon us this season, symphony orchestras are mounting knee-jerk integral Beethoven symphony cycles, pianists are readying complete sonata cycles, string quartets are preparing full quartet cycles, and so on. Predictably, the milestone is giving the classical recording industry—or, rather, what’s left of it—another excuse to repackage their back catalogue, on the assumption that the musical public can never get enough of Ludwig van’s Greatest Hits.

Following recordings—ideally with score in hand—is arguably the best means by which serious music lovers can fortify themselves for the coming barrage of Beethoven. But which recordings should they go with? There are literally thousands of Beethoven discs and DVDs on the market, and much that is available for free on YouTube. Choosing the “best” among that sonic welter is impossible.

It comes down to how you like your Beethoven. Modern or period instruments? Full symphony orchestra or smaller ensemble? Classical or romantic? Traditionally grand or contemporaneously lean and mean? The plain fact is that no single performer or orchestra or ensemble can fully encompass the infinite variety of expression of Beethoven’s music.

With that in mind, consider the following list of recommended Beethoven recordings a guide rather than a manifesto. Ultimately it will be your personal tastes that determine what winds up in your home listening library.

SYMPHONIES

No fewer than 37 Beethoven symphony cycles currently crowd the catalogue, with several more likely to be issued, and reissued, as the “Beethoven 250” festivities continue. Rather than go with one conductor or orchestra, many listeners will want to pick and choose among individual symphony recordings.

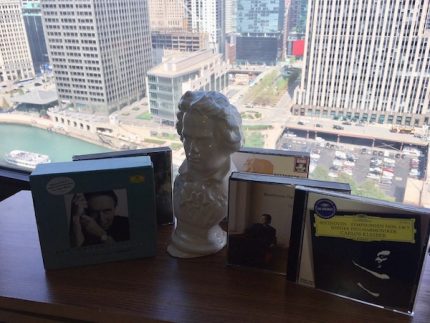

One can do no better than the urgent Eroica symphony led by Gunter Wand (RCA); the titanic Carlos Kleiber coupling of Nos. 5 and 7 (DG); Bruno Walter’s unhurried gambol in the Pastoral countryside (Sony); or the legendary Beethoven Ninth recorded live under the great Wilhelm Furtwangler’s direction at the reopening of the Bayreuth Festival Theater in 1951 (Warner or Orfeo).

If it’s a modern, full-orchestra cycle you’re after, try the life-affirming set Claudio Abbado made with the Berlin Philharmonic, on DG. (As a kind of pendant, you should also investigate a fine collection of 11 Beethoven overtures Abbado recorded with the Vienna Philharmonic, also DG.)

Of the several historically minded cycles played on period instruments, the Archiv box with John Eliot Gardiner leading his Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique remains a revelatory achievement. These performances tingle with a crisp, bracing vitality even those stalwart revisionists Nikolaus Harnoncourt and Roger Norrington cannot quite equal in their integral sets.

Gardiner and the ORR will be touring the nine Beethovens across the U.S. next winter—including an eagerly anticipated, five-concert stop at the Harris Theater for Music and Dance in downtown Chicago, Feb. 27-March 3. It will be fascinating to experience his current thoughts on these touchstone symphonies.

Overlapping the Gardiner performances in Chicago will be Riccardo Muti’s season-long Beethoven symphony cycle with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. A greater disparity between stylistic approaches could hardly be imagined. Whereas the “authentic” Gardiner opts for streamlined bite—often approaching Beethoven’s controversially fast metronome markings—the more traditionally minded Muti, on his EMI (now Warner Classics) set with the Philadelphia Orchestra, favors burnished beauty of sonority, Italianate singing lines and fast movements that tap into the Beethovenian life force, often to thrilling effect.

PIANO CONCERTOS

The situation here is much the same as with the sonatas: You pays your money and you takes your choice. Those master Beethovenians Alfred Brendel and Daniel Barenboim have taken this repertoire into the studio multiple times over the years, and each brings something deeply personal to it, in his own way. Brendel is best heard on his third and final survey, made with the Vienna Philharmonic under Simon Rattle (Philips); Barenboim, with the series of youthful recordings he made with Otto Klemperer in London in the late 1960s (EMI).

As for modern recordings of the five concertos, no pianist-conductor team challenges received interpretative wisdom more cogently than Pierre-Laurent Aimard and Nikolaus Harnoncourt; their Teldec set brings a bracing sense of renewal to this well-trodden repertoire that is wonderfully free of willfulness.

Listeners who prefer to cherry-pick single-disc versions of these masterpieces are directed to pianists Murray Perahia in No. 1 (Sony), Martha Argerich in Nos. 2 and 3 (DG), and Emil Gilels in Nos. 4 and 5 (EMI).

VIOLIN CONCERTO / TRIPLE CONCERTO

This listener’s loyalty to such classics of the stereo era as Itzhak Perlman (with the Philharmonia Orchestra under Carlo Maria Giulini) and Jascha Heifetz, partnered by Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony Orchestra (RCA) remains undimmed. Each interpreter has something special to say about this music. Of the more recent contenders, Harmonia Mundi’s digital offering with the radiant Isabelle Faust is remarkable in its fusion of expressive intensity and lyrical beauty.

As for the patchy but prophetic Triple Concerto, no recent version has surpassed the magisterial 1969 account by the million-dollar trio of violinist David Oistrakh, cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, and pianist Sviatoslav Richter, with Herbert von Karajan at the helm (Warner and EMI).

STRING QUARTETS

The monaural, stereo and digital eras all have produced distinguished cycles of Beethoven’s 16 string quartets. All of these must bow to the legendary cycle that the Budapest String Quartet recorded for Columbia between 1951 and 1952. Sony has reissued these recordings in a remastered, 12-CD box—a basic-library set if there ever was one. The Takács Quartet is a worthy alternative if modern sound is an important consideration (Decca).

Those who would prefer cozying up to this chamber repertoire more selectively, and in modern sonics, should check out the early-period quartets as recorded by the Quartetto Italiano (Philips), the middle quartets by the Emerson Quartet (DG) and the late quartets by the Alban Berg Quartet (Warner).

VIOLIN SONATAS / PIANO TRIOS

With this repertoire one is torn between the exciting volatility and inner tension of the recently issued complete set by violinist Gidon Kremer and pianist Martha Argerich (DG), and the mix of spontaneity and silken, classical refinement of the classic 1970s edition from Itzhak Perlman and Vladimir Ashkenazy (Decca). Ultimately the complete Beethovenian should have both versions on his or her shelf. Listeners wishing to dip their toe into these chamber masterpieces are directed to the Kreutzer and Spring sonatas as recorded by Yehudi Menuhin and Wilhelm Kempff (DG).

Perlman and Ashkenazy are joined by cellist Lynn Harrell for an integral set of the 11 piano trios whose probing performances pretty much have the field to themselves (Warner).

PIANO SONATAS / DIABELLI VARIATIONS

If Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier represents the pianist’s Old Testament, the 32 Beethoven piano sonatas are their New Testament. With this repertoire, the rewards of having a single interpreter’s view laid out before the listener in complete recorded form are arguably even more pronounced than with the symphonies.

For a modern edition of performances that combine power, gravitas, lyrical sensitivity and luminous tone in satisfying proportion, one must strongly recommend the 1993 set made by the brilliant Richard Goode (Nonesuch). Just as probing, albeit solidly in the Austro-German tradition, is the monaural traversal by the German master Wilhelm Kempff, at times more individual and compelling than his stereo remake (both DG). There is also much to be said for the spontaneous romanticism of Daniel Barenboim (EMI and DG) and the articulate classicism of Alfred Brendel (Philips).

Among individual recordings of the more popular sonatas you have a wide range of worthy options, including Sviatoslav Richter for the Hammerklavier (various labels), Arthur Rubinstein for the Moonlight, Pathetique and Les Adieux sonatas (RCA), and Murray Perahia for the Appassionata (Sony).

The 33 variations Beethoven wrote on a trivial waltz by Anton Diabelli represent the Everest of keyboard variations, and three great pianists—Alfred Brendel, Sviatoslav Richter and Claudio Arrau—scale the music’s heights with a strength of manner and a generosity of spirit that have never been surpassed on disc. All three CD performances are on Philips.

MISSA SOLEMNIS

Beethoven’s late testament of religious belief falls into that category of masterpieces pianist Artur Schnabel classified as being “greater than they can be performed.” To these ears, the DG Archiv recording by John Eliot Gardiner, with the Monteverdi Choir and period-instrument English Baroque Soloists, gets to the heart of the matter better than any larger-scaled “traditional” version. This, quite simply, is one of the greatest Beethoven recordings ever made.

FIDELIO / LIEDER

With audio versions of Beethoven’s only opera the choice is relatively easy. While an electrifying digital version (Decca), recorded live at the 2010 Lucerne Festival, with Nina Stemme as Leonore and Jonas Kaufmann as Florestan, under the baton of Claudio Abbado, has plenty to recommend it, the 1962 EMI studio set led by Otto Klemperer—with Christa Ludwig and Jon Vickers singing the performances of their lives—remains unsurpassed.

Beethoven’s contributions to the art song repertoire may be less important than those of Schubert, Schumann and Brahms—also far less extensive—but, at their finest (as in the cycle An die ferne Geliebte), one experiences a side of his art that deserves to be much better known. In a 1965 Salzburg Festival recital, the great German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, in partnership with pianist Gerald Moore, brings a selection of these underrated vocal gems to life, splendidly (Orfeo).

MISCELLANY

Berlin Classics has gathered a wealth of seldom-heard Beethoven chamber and vocal pieces—who knew the master wrote duos for mandolin and piano?—and gathered them in three multi-disc sets titled “Der Unbekannte Beethoven” (“The Unknown Works”). The German performers, including the Leipzig Radio Chorus and the Erben Quartet, rise capably to the occasion.

“Funny Beethoven” might seem a contradiction in terms, but pianist Leonid Hambro has concocted that very thing with his original solo piano piece “Happy Birthday Ludwig”—a 12-minute series of variations on the familiar tune, done up in the style of the Fifth Symphony, Moonlight Sonata and so on. Originally included on a Beethoven-compilation LP Columbia released to mark the master’s 200th birthday, this amusing novelty can be found on YouTube.