Mälkki, Chicago Symphony ignite a summer storm with epic Sibelius at Ravinia

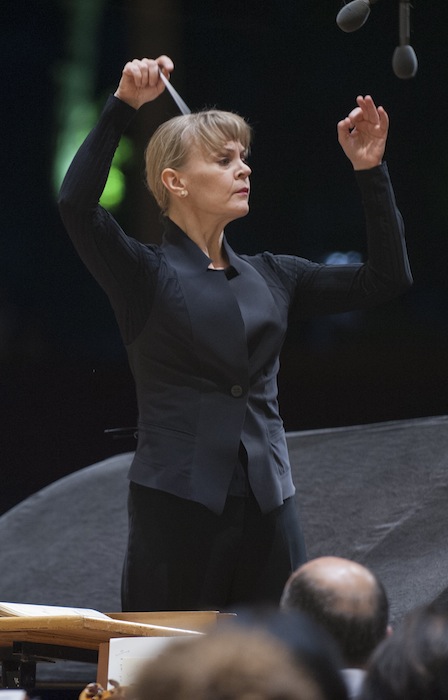

Susanna Mälkki conducted the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in music of Sibelius and Beethoven Friday night at the Ravinia Festival. Photo: Pedro de Jesus/Ravinia

To quote the festival’s marketing line, it really was a great night at Ravinia—musically, if not meteorologically.

Friday’s late afternoon rains thinned out the lawn audience and the thunderstorms returned with a vengeance after intermission, helping to make the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s performance of Sibelius even more intense and dramatic. Not that it needed any help.

With her regular CSO appearances downtown, Susanna Mälkki has become a Chicago favorite in recent seasons. In the final of her two consecutive Ravinia programs this week, the Finnish conductor led her first local performance of a Sibelius symphony. And Friday night’s grand and impassioned performance of the Symphony No. 2 showed once again why Mälkki is among the most exciting and illuminating of CSO podium guests.

For the aficionados in the audience there was a clear sense of anticipation in hearing Mälkki conduct music of her country’s greatest composer. Granted, it’s something of a fool’s game to impute an innate sympathy to music of a conductor’s compatriots since one can find just as many conductors of other nationalities who are adept in the same repertoire (and, often, some from the same country of origin who are not).

The current trend among many conductors is to treat Sibelius’s first two symphonies from the vantage point of the composer he was to become rather than the Russian tradition his music was emerging from. Viewing these early works as developmental road markers, the approach is to underline the nascent austerities of his mature style, while playing down the Romanticism.

This was not Mälkki’s way. While there was no lack of elemental Northern atmosphere, she clearly sees the Second Symphony in the Romantic tradition. In the political word of the moment, this was big Sibelius—huge textures built from the bottom up, with deep, rumbling cellos and double-basses, and eruptive, powerful brass and percussion. The evening’s roiling storm added to the cumulative sonic impact, providing thunder and lightning almost on cue at the climax of the first movement and again in the finale.

While imposing, tough and elemental, there was also an epic breadth and spaciousness. Mälkki directed each movement with a firm yet flexible pulse and sense of the long line–we always felt where each movement was headed and how it fit into the larger whole.

Sibelius’s singular handprints came across with an extra degree of color and sonic impact—the forlorn wind solos, jagged brass phrases, and undulating cellos and basses. With her acute balancing making manifest the orchestra sections moving at different speeds, Mälkki’s inexorable ratcheting up of volume and adrenaline to the majestic climax of the finale was thrilling and spectacular.

The CSO musicians played with total commitment and, even with the challenging conditions and short rehearsal time, this Sibelius Second proved a highlight of the musical year. As is increasingly the case in summer weeks, many of the principals were off, but that had little effect on this rich and vividly characterized performance, with fine contributions from clarinetist John Bruce Yeh, oboist Michael Henoch and guest trumpet David Krauss, principal of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra.

The first half of the evening was on the same estimable level with Mälkki and Kirill Gerstein simpatico partners in Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3.

Gerstein is one of those rare artists who seems wholly convincing in whatever music he happens to be playing, and Friday he gave a virtual seminar in idiomatic Beethoven style. Natural and purposeful throughout, Gerstein strongly served the lean and dramatic opening movement yet shifted gears seamlessly for the quirky, lighthearted bonhomie of the finale. Despite the triple-fortissimo obbligato by the park’s cicada tabernacle chorus, Gerstein managed to explore a nuanced degree of inner expression in his searching Largo.

Mälkki and the CSO supported Gerstein with comparably incisive accompaniment and accents firmly marked. The final pages of the slow movement were as rapt and lovely as one could ever hope to hear.