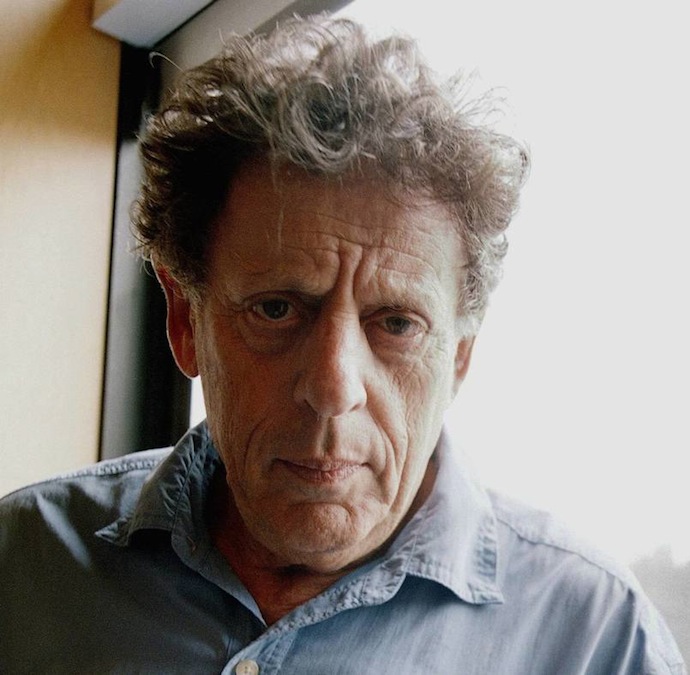

With birthday bash on tap, Philip Glass talks about reaching 80 years and 11 symphonies

Philip Glass’s Symphony No. 11 will have its world premiere Tuesday night at Carnegie Hall on the composer’s 80th birthday.

For Philip Glass, the birthday present came early.

Wednesday morning, Carnegie Hall announced that he will hold Carnegie’s Richard and Barbara Debs Composer’s Chair for the 2017–18 season; the season will feature performances of new and classic works from the composer.

But there’s still going to be a party. On Tuesday, January 31, the very day Glass turns 80, the Bruckner Orchester Linz and conductor Dennis Russell Davies will perform the world premiere of Glass’s Symphony No. 11 at Carnegie, in an all-Glass program that will also include Days and Nights in Rocinha and the New York premiere of Ifé: Three Yorùbá Songs, featuring the crystalline, clarion singing of Angélique Kidjo.

Glass has always been a classical composer in the most traditional sense, using the basic tools of counterpoint, voice leading, and harmony. His early instrumentation of electric organs—often borne out of necessity—was as controversial as his repetitive forms, and often clouded stubborn ears to what was actually going on.

That the composer of Music in Twelve Parts and Einstein on the Beach has evolved into a major symphonist is no surprise—it’s the result of an artist following his own singular path for decades.

In the 21st century, the symphony may seem old-fashioned, and in an interesting way, Glass’ symphonies are indeed old-fashioned. They come out of a long and unique collaboration with Davies—the conductor premiered Symphony No. 1, “Low,” based on David Bowie’s great 1992 of the same name. Davies was appointed music director of the Linz orchestra in 2002, and since then the orchestra has recorded each of Glass’ symphonies from No. 6, “Plutonian Ode,” on, and premiered Nos. 8 and 9.

In a recent interview, Glass is full of praise for the orchestra: “The Linz orchestra has made definitive recordings of Bruckner. This is what they do—this is a wonderful, high art, European orchestra. And I have to tell you, I never thought a European orchestra would ever play this music as well as an American one. When I hear them play my music it sounds like, ‘It can really sound like that too’, and they bring a profound respect for the history of symphonic music, and we all benefit from that.”

The multifaceted connection with Bruckner is both real and coincidental. The premiere will come immediately after New York audiences immersed themselves in the complete Bruckner symphonies, via the cycle from Daniel Barenboim and the Staatskappelle Berlin. And Bruckner is a composer who runs deep in Glass’s aesthetic. In his memoir, Words Without Music, Glass mentions Bruckner as an early influence, and his sense of form is extremely sympathetic to that of the 19th century symphonist.

“I discovered this music in my teens. Bruckner was hard to find—there was Fürtwangler, there was Bruno Walter.” Glass and a group of friends at the University of Chicago used to gather together and listen, compare recordings, study scores. Like Bruckner, Glass is interested in polyphony and structure without the standard method of development, “I’ve given myself permission to drop it.”

His new symphony, No. 11, is in three movements. “Three is a common number for me. It would even be possible to close the gap between the movements and it would work quite well played straight through. Maybe it’s good to take a break, though I’m ambivalent about this—once you get tuned into the piece it’s easy to stay with it all the way. It’s forty minutes, that’s a medium-size orchestra piece for me.”

As for his thoughts on symphonic form, Glass says, “I don’t really know, I’m still asking myself that same question, I’m wondering how things work. Each of the symphonies, what’s interesting about them is they all sound different, but they all sound like they were written by the same person.

“I don’t really anticipate what’s going to happen until I start [composing], I don’t have notes ahead of time. I hadn’t even thought of three movements, I thought it was going to have a slow middle movement, but it turned out it didn’t, and I said, ‘Oh well, I guess it didn’t!’ This piece has a drive that takes you all the way through it.”

Of course, writing eleven symphonies is one thing, having each of them performed and recorded is another. and the result of the dedication that Glass and the musicians share with each other. A box set has recently been issued on Glass’s Orange Mountain label of his symphonies Nos. 1-10 conducted by Davies.

“Dennis Russell Davies has been a friend and collaborator for a long time… I’ve had a lot of pieces played by the [Linz] orchestra, and I went back almost every year, and I got to know the orchestra, I got to know them intimately in a way that I dare say no American composer can say about any orchestra. It was that relationship that was nurtured and developed, and you’ll hear that Tuesday. I’ve written many pieces for them over the years, I know them personally, I know who they are, I know what they sound like.”

This was an ideal, but exceptional, pre–20th century model for orchestral composition, unheard of in the 21st century. “We don’t have that here,” Glass points out. “We have other things in America, a kind of independence which is also very good, we’ve developed that. We have a freedom the Europeans don’t have, but we can also be missing something too.

“I’ve been fortunate, because I’ve worked in both places. I’ve played a lot in Europe with my ensemble, and I was accepted more easily than I was in America. Now [I’m] at Carnegie Hall! This is my year.”

Dennis Russell Davies and the Bruckner Orchester Linz will present the world premiere of Philip Glass’s Symphony No. 11, 7:30 p.m. Tuesday at Carnegie Hall. carnegiehall.org