A terrific cast shines brightly amid the mixed mechanics of Lyric Opera’s “Rheingold”

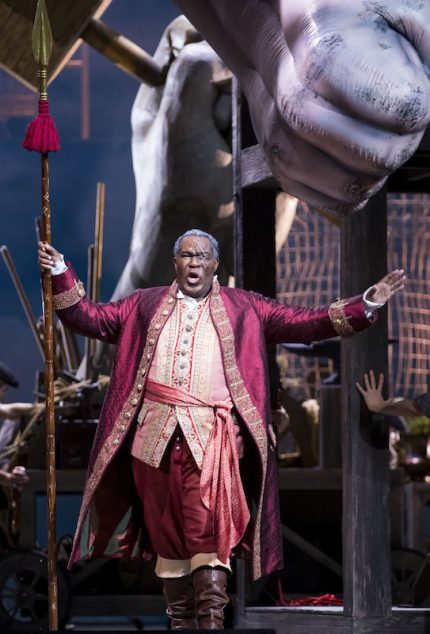

Eric Owens is Wotan in Lyric Opera’s new production of Wagner’s “Das Rheingold.” Photo: Todd Rosenberg.

For those wary of stagings of Wagner’s “Der Ring des Nibelungen” that reset the action on Mars or in a Nazi prison camp, the good news is that Lyric Opera of Chicago’s production of Das Rheingold, which opened the company’s season Saturday night, largely plays the action straight. Or, at least as straight as one can, in a fantastical tale of greed, ambition, lust, gods, giants, evil dwarves, and the end of the world.

The much-anticipated production, which launches a new Lyric Ring cycle, had some lapses along the way, to be sure. But director David Pountney’s coolly modernist, play-within-a-play staging didn’t get in the way of Wagner’s glorious music, and for the most part provided a theatrical and intriguing backdrop for the cycle’s “Preliminary Evening.”

Das Rheingold opens Wagner’s tetralogy with the tale of Alberich, the malign dwarf rejected by the Rhinemaidens, who steals their gold and renounces love to gain vast fortune and power, fashioning his treasure into a golden ring. Wotan, king of the gods, is admiring his new fortress Valhalla, yet must contend with its builders, the giant brothers Fasolt and Fafner who take his sister-in-law Freia hostage for his refusal to pay for their labors. Advised by the cynical fire god Loge, Wotan steals the Rheingold away from Alberich, who curses the ring and all who possess it to death and destruction forever. Warned by Erda the earth goddess, Wotan reluctantly cedes the ring to the giants and Alberich’s curse immediately claims its first victim when Fafner kills Fasolt. The gods enter Valhalla, as the Rhinemaidens bewail the loss of their treasure.

The production by director Pountney and scenery designer Robert Innes Hopkins–based on designs by the late Johan Engels–presents a behind-the-scenes take on Rheingold, with sets that suggest a cross between the Globe Theatre and Industrial Age. The staging does away with traditional theatrical magic in postmodern fashion, revealing the stage artifice and mechanics, visible crews wheeling scenery and carts onstage and off.

The evening opens in eye-popping fashion, with the Rhinemaidens soaring high and swooping low to tease and evade the overheated Alberich, while the three cranes on which the singers perch are in full view of the audience, along with the stagehands operating them.

Just as imposing are the towering, four-story wooden scaffolds that frame the action on either side, revolving to reveal pairs of enormous heads and hands depicting the giants Fasolt and Fafner; the hands are lowered and worked by stage crews to ensnare Freia and threaten the gods. Also effective are the three stage elevators that depict the descent of Wotan and Loge to the red, furnace-like Nibelheim, where Alberich enslaves his brother Mime and minions to increase his golden hoard. The Norns also make an early appearance in this cycle and are constantly present, silently weaving their earthly strings.

Sadly, the production falls short in the opera’s most crucial moments. With crews always visible operating the scenery, the stage action often became crowded and chaotic. The Rhinemaidens’ gold stolen by Alberich resembled an antique lighting fixture swiped from an English pub. The impact of Fafner’s murder of Fasolt was diluted and visually confused, with the singers portraying the giants perched high above and the giant hands punching below, like Rock’Em Sock’Em Robots on steroids.

Most crucially, the climactic entrance of the gods into Valhalla proved a hollow letdown. The staging attempts to knock down the fourth wall, with the gods lined up, oddly slow-waltzing their way to the heavens via a succession of images of Lyric Opera’s painted stage curtain. The Rainbow Bridge is depicted, lamely, by brightly colored ropes leading to a tiny golden mockup of the stage set–suggesting less a majestic ascent into Valhalla than a pesky security line en route to a Pride event.

That misfire illustrates the production’s broader failing, one of tone and balance. God knows, there are many opportunities for humor–intended by Wagner and not–in Rheingold. But the approach of Lyric’s current production leans heavily toward the jokey and satiric, playing the action for laughs via costuming and visual gags–as with Loge’s entrance on a bright-red three-wheeled bicycle, and Alberich transforming himself into a serpent and frog by blowing up inflatable backpacks. The serious themes and philosophical depth of the work get decidedly short shrift, and in their attempts to demythologize Rheingold, Pountney and company too often seem to be goofing on Wagner’s opera, rather than illuminating it.

The prevailing irony makes the production’s biggest blunder seem even more out of place, with Wotan cutting off Alberich’s arm to gain the ring, a bloody bit of postmodern excess that suddenly turns the god into a violent sociopath and casts a pall over the rest of the evening. That business likely contributed to the scattered but robust booing that greeted Pountney and the rest of the production team at the curtain call.

Still, most of Pountney’s staging at least worked on its own terms, which is more than one can say for Marie-Jeanne Lecca’s costumes, which veered between bizarre and disastrous. There was nothing timeless nor evocative in Lecca’s campy, baffling getups. Wotan and Loge are attired in red Restoration-era coats, strangely evoking British generals in the Revolutionary War, and the gods’ elaborate feather hats looked like castoffs from The Three Musketeers. The god Froh gets an Asian motif for some reason and wears a fez. (Is he a Shriner?)

Production issues apart, Lyric’s Rheingold was an almost unqualified success musically, marking several impressive singer debuts.

Unfortunately, the single disappointing performance came from the evening’s star, Eric Owens. The bass-baritone has enjoyed several successful outings at Lyric and has won acclaim for his Alberich around the world, leading general director Anthony Freud to tap Owens for his first stage outing as the king of the gods.

Owens possesses an imposing instrument but he seemed vocally ill-suited to the role of Wotan, which calls for a wider vocal range than Alberich. He appeared to struggle at both ends, with short-breathed singing and a lack of sustaining weight for Wotan’s big moments. As the unbroken 2-1/2 hour action unfolded, the big singer seemed to lose stamina, reflected in Owens’ sedentary Wotan sitting in a chair admiring his Ring for most of the final third of the opera. Even with that staging assist, Owens seemed to be on fumes by the final scene, with Wotan’s praise of Valhalla effortful and sorely underpowered. Dramatically, Owens fared somewhat better without quite bringing a convincing nobility and gravitas to the role.

The rest of the large cast was vocally faultless from top to bottom. As Fricka, Wotan’s querulous wife, Tanja Ariane Baumgartner made a most successful U.S. debut. Tall and elegant, the German mezzo was an aptly regal presence and her warm, refined singing provided consistent pleasure.

Also making his American debut was Samuel Youn, who owned the evening with his staggering portrayal of Alberich. The Korean singer–who has also performed the role of Wotan to high praise–proved sensational both vocally and dramatically. Whether lusting after the Rhinemaidens, beating Mime and his workers, or boasting of his riches, Youn brought searing dramatic intensity to the role of the embittered dwarf. His sturdy, flexible bass-baritone handled all the role’s myriad challenges, and Youn’s delivery of Alberich’s curse was for once the darkly bone-chilling moment Wagner intended.

Stefan Margita is the finest Loge in opera today, and the veteran Slovakian tenor was the clear audience favorite opening night. His energetic performance as the fire god trickster crossed over into ham territory at times, with his director seemingly encouraging Margita’s over-the-top scenery-chewing rather than reining him in. Still, no one does Loge better, and Margita’s sinuous, liquid-like voice perfectly evokes the character of Wotan’s wily, Iago-like advisor. The tenor looked surprised and touched by the vociferous ovation he received at the curtain call.

As Fasolt and Fafner, Wilhelm Schwinghammer and Tobias Kehrer, respectively, proved a well-matched pair of deep-voiced fraternal giants, singing well and seemingly untroubled by their high positions on the scaffolding. Schwinghammer made the doomed Fasolt’s love for Freia affecting and Fafner’s sudden act of violence was firmly delivered by Kehrer.

Laura Wilde was a worthy Freia; her caressing of Fasolt’s giant hand and rejection of the gods after her release brought a new and somewhat unsettling Stockholm Syndrome twist to her captivity. Rodell Rosel’s juicy character tenor and acrobatic energy enlivened the fearful, resentful Mime.

The sudden appearance of the earth goddess Erda was the sit-up-in-your-seat moment it should be, with Okka von der Damerau’s dark and refulgent mezzo making her prophetic warning to Wotan an evening highlight.

The gods Donner and Froh are usually played for laughs these days as not-too-bright, would-be alpha males, and such was the case again. Even so, baritone Zachary Nelson was effective in Donner’s summoning of thunder, and Ryan Center tenor Jesse Donner’s fine vocalism as Froh managed to overcome his unfortunate costuming.

One will rarely encounter a finer trio of Rhinemaidens than that served up in this Lyric staging. Diana Newman, Annie Rosen (both Ryan Center members) and Lindsay Ammann were a fearless trio, lolling about on the high cranes, singing magnificently, and bringing leggy sensuality to the temptress roles, which made Alberich’s feckless lusting wholly credible.

Andrew Davis’s Wagnerian bona fides are well known by now. His conducting was fluent, meticulously balanced and always supportive of the singers while keeping the action moving as surely as the rolling of the Rhine. Apart from a brief brass fluff in Donner’s storm summons, the playing of the Lyric Opera Orchestra was as polished, responsive and idiomatic as one would expect from this highly experienced Wagner ensemble.

Das Rheingold runs through October 22. lyricopera.org; 312-827-5600.