On a cool night, Grant Park Music Festival serves up cool Czech rarities

Bohuslav Martinů’s “The Epic of Gilgamesh” was performed Friday night at the Grant Park Music Festival.

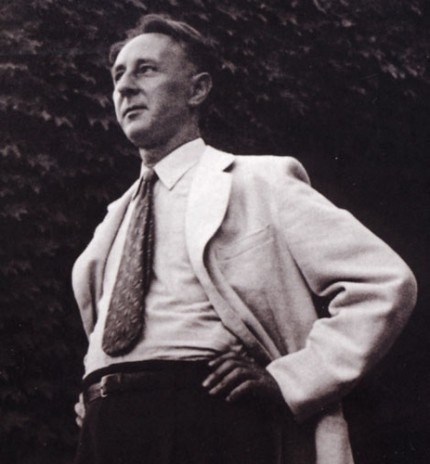

More than fifty years after his death, Bohuslav Martinů’s music remains inexplicably neglected.

One of the most prolific composers of the 20th century, Martinů wrote successfully in every genre, including six symphonies, nine concertos, and reams of chamber music, including eight string quartets and three piano quintets. The Czech composer’s music is of a consistently high quality, his style an attractive middle ground between Neo-classicism and a lean Romanticism–lyrical yet with an astringent edge.

Carlos Kalmar led the Grant Park Orchestra and Chorus in Martinů’s The Epic of Gilgamesh on an unseasonably cool Friday night at the Pritzker Pavilion. Who else in Chicago but Kalmar would have the audacity to program this obscure, 50-minute Martinů oratorio?

Written in 1955, four years before the composer’s death, The Epic of Gilgamesh is based on ancient tales of the title Sumerian king of Uruk. In these mythic fables, Gilgamesh is an oppressive swine of a semi-god. The gods send the equally cretinous Enkidu to distract him from continuing to do, what Kalmar termed in his introduction, some “not very nice things.” An encounter with a prostitute teaches Enkidu about passion and humility. Angry at Gilgamesh’s abuse of his people, Enkidu fights with him, though no one wins. After, the two men make up–presumably over a Mesopotamian beer–and become the best of friends. Enkidu is killed by the gods and after trying unsuccessfully to raise him from the dead, the heartbroken Gilgamesh mourns the loss of his friend.

There are, unsurprisingly, issues with The Epic of Gilgamesh. The three-part structure is episodic and Reginald Campbell Thompson’s tweedy translation is replete with dated English terms and comically awkward syntax.

Yet even with that, the music Martinů composed to depict this bizarro Babylonian bromance is never less than compelling and often magnificent. Scored for four soloists, large double chorus and orchestra, the score is as varied and finely crafted as Martinů’s (somewhat) more familiar works. A piano adds acerbic bite to the orchestral textures and the choral writing is imaginative and audacious, as with the wordless vocalise for solo soprano and chorus in Part Three.

Under Christopher Bell’s direction the Grant Park Chorus was terrific across the board in this lakefront festival premiere. From their imposing opening cry of “Gilgamesh!” every word was crystal clear even at low dynamics. The ensemble singing was impeccably blended, as luminous in quiet moments as it was powerful in climaxes.

The soloists in “Gilgamesh” Friday night were (l. to r.) tenor Dane Thomas, bass Gidon Saks, baritone David John Pike, and soprano Angela Meade. Photo: Norman Timonera

The solo quartet was largely on the same level. Angela Meade’s words could have been clearer at times, yet this gifted soprano brought rich, luxuriant tone to her brief moments.

David John Pike showed a robust baritone as Gilgamesh yet his singing too often centered on a kind of generalized vehemence. Such moments as the death of Enkidu would have benefited from greater dramatic intensity.

Dane Thomas was the capable tenor soloist. Gidon Saks was most impressive of all, displaying a sonorous bass-baritone and bringing committed expression to his solos. Veteran music critic Bernard Jacobson was the clear-voiced and sensitive narrator.

Give all credit to Kalmar for not only pulling this sprawling score together but for putting it across with such passion and conviction. The varied beauties of the score were conveyed throughout by the superb playing of the Grant Park Orchestra, from the mystery of the introduction to the battle between Gilgamesh and Enkidu, and the climactic final section for chorus and soloists. Kudos to the Grant Park Music Festival for bringing us this offbeat rarity and for remaining Chicago’s most adventurous and forward-looking classical organization.

Late in life Antonin Dvořák wrote four tone poems based on the macabre folk tales of Karel Jaromir Erben. These large-scale works seem to be slowly working their way into the regular repertory, and one of them, The Golden Spinning Wheel, began the all-Czech evening in its festival premiere.

The Golden Spinning Wheel tells the tale of a king on horseback who meets and falls instantly in love with Dornicka, a young girl he meets at her spinning wheel. Her evil stepmother, unfortunately, is jealous, having an unmarried daughter of her own. She kills Dornicka and dismembers the girl, substituting her own daughter in her place (unsuspected by the apparently visually challenged king). Ultimately, and improbably, the girl is somehow reconstituted with parts of the spinning wheel by a strange forest beggar, and magically brought back to life.

The frolicsome scenario apart, the music is less violent than the story suggests, centered on a regal pomp for the king and court and a melancholy lyricism for Dornicka.

Kalmar, who also provided a charming and humorous introduction, clearly has the measure of this nearly 30-minute work. With a firm, flowing momentum, Kalmar drew a vivid, well-characterized performance with each episode registering with sure impact. Brass and woodwinds were especially evocative and concertmaster Jeremy Black brought an affecting, fragile tenderness to Dornicka’s violin theme.