Guerrilla theater: Current events make Lyric Opera of Chicago’s “Bel Canto” a timely premiere

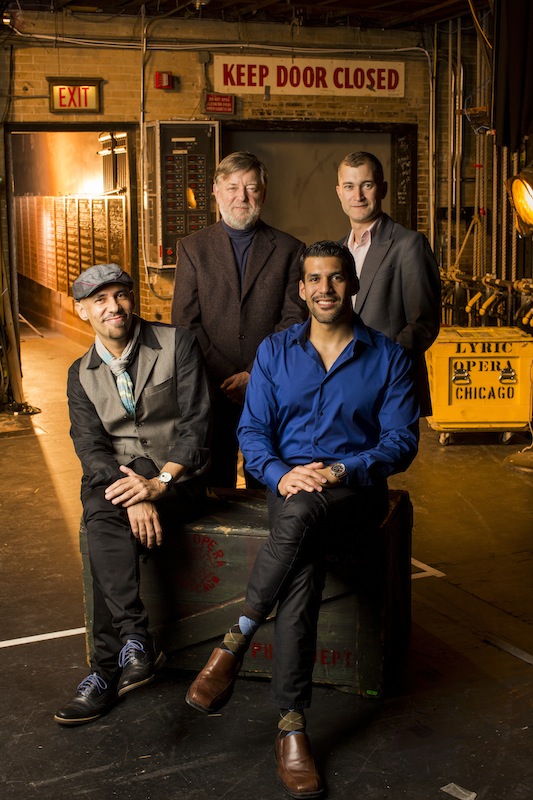

The “Bel Canto” creative team: Nilo Cruz and Jimmy Lopez (front, left to right) and Sir Andrew Davis and Kevin Newbury. Photo: Todd Rosenberg

It is a young composer’s first opera, a playwright’s first libretto, and an opera company’s ‘s first world premiere in more than a decade. Its raw material is a real-life act of political violence; its subjects include terrorism and inequality.

Perhaps most crucially, it arrives on one of America’s major opera stages at a moment of renewed global anxiety, following terrorist attacks by armed extremists in Paris and just this week in San Bernardino, California.

Even by the degree of risk-taking that any new opera entails, Bel Canto stands out.

There are enough firsts and overlaps between art and life in play to launch a reality show around Lyric Opera of Chicago’s highly anticipated production. Bel Canto debuts Monday night at the Civic Opera House, in a test of the company’s commitment to new works and a leap into fraught topical and emotional territory.

Tackling it could rate as “either brave or foolhardy — I don’t know which,” says Lyric music director Sir Andrew Davis. “Nothing ever goes seamlessly in opera.”

Based on Ann Patchett’s 2001 novel of the same name about an American opera singer caught up in a foreign embassy assault, Bel Canto might be the first work in opera history to come with a safety label.

“[T]he production contains scenes of violence, and includes loud theatrical gunfire,” wrote Lyric’s general director, Anthony Freud, in a letter to subscribers.

Managing current events has suddenly become part of Freud’s administrative brief. Just three weeks ago, with Paris still in shock, he stood on the Civic Opera House stage at the opening performance of The Merry Widow, asking patrons to stand for a performance of the Marseillaise in honor of the French victims of last month’s attacks.

But well before the news cycle collided with the Lyric’s long-planned performance calendar, Bel Canto was fanning expectations because of its primary champion: real-life opera star Renée Fleming.

Fleming has steered the project from conception to curtain — a first for her, too, as the Lyric’s inaugural “creative consultant.” She was rumored to be the inspiration for Patchett’s besieged diva, Roxane Coss. (Fleming and Patchett are friends, although they met after the book was published.)

But Fleming won’t be singing the lead role Monday night.

“I don’t think it would serve the piece because people would see this as a vanity project for me, and that’s never good,” Fleming told Patchett in a live webcast hosted by the Lyric in November.

The role of Roxane Coss will be premiered by soprano Danielle de Niese, the first singer cast in Bel Canto, even before the Lyric had formally announced it as a company project in early 2012. “It’s really a part that is designed for her,” the opera’s composer, says Jimmy Lopez.

It is not de Niese’s first time singing a new and tailored role, but it is the first experience portraying a character what she essentially is — an opera singer. (Though she did “play” a soprano on screen in Ridley Scott’s 2001 thriller, Hannibal.)

“I think in some way it is a little bit more personal to me, because she’s someone in my profession,” de Niese said of Roxanne. “I’m not playing a farmer’s daughter, and it is very personal, and it’s very intense.”

Several key players of the team for this first Lyric world premiere since William Bolcom’s A Wedding in 2004 sounded more motivated than unnerved by the tensions and uncertainties associated with building an opera from scratch.

But they did not minimize the difficulties either: massing a huge cast on a single set and dramatizing a months-long hostage crisis with intimate internal subplots and intrigues, all in two tight acts.

“This is one of the most challenging and rewarding rehearsal processes of my career,” says director Kevin Newbury. “There are one hundred people on stage at the same time, and they can’t leave.”

“One bar at a time” is how de Niese described Bel Canto’s painstaking preparation, with rehearsals advancing through the libretto at about a half-page per hour — slower than anything she had ever done before, but “completely worth it,” she said.

The libretto is likewise a new endeavor for Nilo Cruz, a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright (for Anna in the Tropics in 2003) who says he found that writing for an opera has more in common with theater than not.

“I think it’s familiar territory for me as a playwright,” said Cruz. “But I was aware that I was serving another medium of art, and certainly that I was serving music here, and I had to economize in terms of language and in terms of the story as well. So it felt familiar and yet it was a challenge.”

Cruz was adapting Patchett, who was drawing on reality: the Japanese embassy hostage crisis of 1996-1997 in Lima, Peru, in which leftist rebels stormed the ambassador’s residence during a lavish reception and held scores of guests captive for 126 days. Peruvian troops ended the standoff by raiding the compound and killing the insurgents.

Patchett’s novel, set in an unnamed South American country, imagined how people thrown together violently, as mortal adversaries, coexist behind barricades once the hours turn to days, weeks and months. More broadly, Bel Canto presents music as a bridge across stark national, economic and cultural divides. In the novel, the world-famous soprano Roxane (a Chicagoan, as it happens) is called upon to sing while in captivity.

Cruz’s libretto re-introduces some of the actual details of the terrorist siege, locating it in Peru and specifying the rural-indigenous militia, the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement, that carried it out. But he retains the novel’s basic contours and the chaotic, polyglot air of a jam-packed diplomatic party that gets taken over.

Nine different languages are sung in Bel Canto, and the friction between countries and classes is evident even before the shooting starts (in the middle of a concert for reception guests.)

In one early scene from the libretto, a sour Russian diplomat singing in French sniffs, “L’Amérique latine m’a toujours flanqué une trouille bleue.” (“Latin America has always scared the living hell out of me.”)

Notwithstanding the occasional one-liner, Cruz and composer Lopez decided that for the most part, the more whimsical tone of the novel — published in the spring of 2001 — wasn’t quite right for the opera or for the times in which it arrives.

“The novel was written before 9/11, and after 9/11 everything changed,” said Cruz. “So I felt I had to look at the novel in a different light.

“That doesn’t mean that this is a completely serious opera; there is playfulness here and there,” said Cruz. “But in the beginning, this is a serious situation and it has to be handled.”

For dramatic purposes, Cruz and Lopez also have made Roxane even more central to the story than she is in the novel, giving de Niese three major arias to sing as she endures a shared ordeal and becomes romantically entangled with another captive, a Japanese businessman who was her secret admirer before they met.

“It was really important for me to have her as an anchor,” Lopez said of Roxane’s character.

The biggest X factor of all in Bel Canto may be Lopez. The highly regarded Peruvian composer, 37, has written music for voice before but never an opera. Lopez was tapped by Fleming in late 2011 from a list of more than 80 candidates.

In talking about Bel Canto, Lopez identifies Verdi’s Rigoletto as a template, for the way in which it uses four principal singers — a central quartet — to lead the opera, tell story and focus narration.

But he hasn’t written his first opera in the eponymous, old world operatic tradition. Lopez is very much a contemporary composer, with a musical language combining traditional and non-traditional tonality as well as western classical and Latin American textures.

He cites Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, as a model: It contains music that is “sensuous, attractive, seductive,” he said, “and then you dig in and see all these complex harmonies.

“I think music should have that quality: grab your attention at once and then invite you to further reach,” said Lopez.

The task of engaging and holding an audience also falls heavily on director Newbury, whose stage in this adaptation is the grand foyer of a Peruvian vice-presidential mansion. The lofty interior, bracketed by winding staircases, is the lone set as well as the screen for visual projections that will signal time passing and changes in dramatic mood.

“A lot of my filming experience has been helpful for a show of this magnitude,” said Newbury.

He also reiterated a point made by others: Bel Canto is a uniquely team venture, with a “best idea wins” approach to problem-solving. Newbury attributed this dynamic in part to the fact that he, Lopez and Cruz — as well as Davis, de Niese and Fleming — all become creative partners very early in the process.

“I knew in the very first meeting that Jimmy and Nilo were going to be great collaborators,” said Newbury.

In his instructions for staging and movement, Newbury has hewed closely to the core-four concept that Lopez borrowed from Rigoletto. But he said that Lopez also wrote some musical passages, on demand, to director specifications, based on exactly how much time — down to the second — Newbury would need for an on-stage sequence.

“I don’t write music and I don’t write words, but I was very involved in the dramaturgy,” said Newbury.

Lopez, in turn, has been present for all rehearsals. “We’re actually there to build the drama together,” said Lopez.

Bel Canto is, to no small degree, an opera about opera, and any resemblance to a prolonged hostage situation may not be entirely coincidental, given the demands of artistic collaboration.

Look closely for long enough, and Bel Canto, the new opera undertaking, starts to resemble Bel Canto the story: a Peruvian composer, Cuban librettist, Australian soprano, British conductor and American curator thrown together in tight quarters for a long time, having to figure things out together without losing it or turning on one another.

Then there is the potential for extra-narrative political fallout. Will some spectators think Bel Canto soft-pedals or even supports terrorism — an accusation lobbed at John Adams for his opera about the intractable Israeli-Palestinian conflict, The Death of Klinghoffer?

“They’re not unsympathetically portrayed,” conductor Davis said of the plot instigators, the self-styled guerrilla generals Alfredo and Benjamin. But Davis said he thinks that the overall story, more than character particulars, wins out.

“I think it has a message that will resonate,” he said.

The Lyric’s general director hopes so, too. In his letter to subscribers, Freud wrote, “At the heart of both the novel and the opera is the idea that humane relationships can develop in the least likely of circumstances.”

“Those of us who care passionately about the arts dream that, in real life, works of art offer insight and maybe even some healing in our turbulent times,” he continued. “I believe that opera is a relevant art form and must not shy away from dealing with contemporary and disturbing subjects. Hopefully, we can play a part in stimulating thought, discourse and debate.”

Bel Canto opens 7:30 p.m. Monday, December 7, and runs through January 17. lyricopera.org; 312-827-5600.