A sensational “Rigoletto” debut and uneven “La fille” at Santa Fe Opera

For one of its standard repertoire pieces this season, Santa Fe Opera has returned to Verdi’s Rigoletto for the first time since 2000, heard on Tuesday night. With a libretto drawn from Victor Hugo’s Le roi s’amuse, Verdi manages to make the two male lead characters, the title jester and the Duke of Mantua sympathetic, even when they are largely repulsive.

Santa Fe Opera’s new production reunites director Lee Blakeley and set and costume designer Adrian Linford, who staged The Grand Duchess of Gerolstein here in 2013. They have reset the time period from the distant past to Risorgimento Italy, the era of the opera’s premiere, with the Duke residing in a rather seedy, run-down palazzo.

This production used a revolving stage, affording glimpses of the palace, Rigoletto’s filthy flat, and the run-down tavern, all with skewed lines, as if collapsing under its own moral vacuity. Between the squalor of sets and costumes and the herd of supernumerary fellatrices in continuous orgy around the Duke, the effect got a little tiresome after a while. Think something like a cross between the moldy garrets of La Bohème and high-fashion heroin chic.

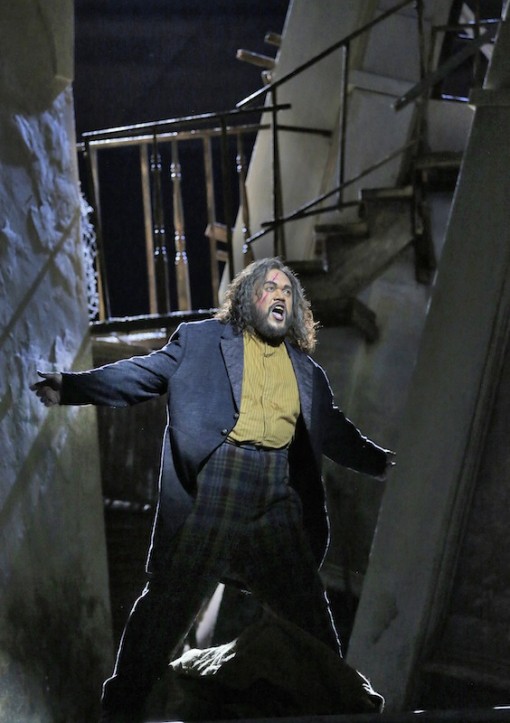

The cast of Rigoletto was exceptionally strong, with one exception. Baritone Quinn Kelsey made a sensational company debut in the title role, with a powerhouse voice that was also capable of luscious tenderness, as in the second act ensemble where he begs the court to let him see his abducted daughter, Gilda (“Pietà, signori”). His was a brutish, hulking Rigoletto, with desperate anger roiling inside him, costumed in a large bowler hat capping his mop of curly hair and lopsided shoes accentuating his limp. Subtlety of interpretation could be improved, for example, in differentiating some of the repeated lines, like “Quel vecchio maledivami!”

Bruce Sledge brought an unexpected guileless appeal to the philandering Duke, with a dulcet tone and sweet-faced presence that buffed away some of the character’s edges, something one regretted only in the fast aria Possente amor. His top notes were all full and beautiful, and he took the serenade La donna è mobile at a dreamy pace that suited it quite well. Sledge’s success was all the more remarkable because he was obliged to take over the entire run of this opera after tenor Bryan Hymel backed out of the production. The tenor has been heard to good effect here in Le Rossignol last year and in his company debut in The Barber of Seville a decade ago.

Georgia Jarman, who was an apprentice singer at Santa Fe Opera in 1997, had an off night in her professional company debut. Slender and pretty, Jarman charmed the crowd and had visual appeal, but she struggled in terms of intonation all evening, especially when the part was doubled in the orchestra.

Filling out the famous quartet in Act II was American mezzo-soprano Nicole Piccolomini, who brought a fulminous tone quality and a sexy stage presence to the role of Maddalena. Peixin Chen was a subdued Sparafucile, with excellent low notes, and stentorian bass Robert Pomakov made Monterone’s oracular pronouncements hard to ignore.

Italian conductor Jader Bignamini, in his American debut, did a respectable job of keeping all the elements together: orchestra, oom-pah-pah banda interna (which was a crack ensemble), and singers and chorus. He was less careful about maintaining instrumental balances, and some parts of the orchestral introduction were especially obtrusive.

_____________

Anna Christy stars as Marie in Donizetti’s “La fille du régiment” at Santa Fe Opera. Photo: Ken Howard

Santa Fe Opera surely met its decennial quota of dippy Donizetti comedies last season, with the company’s production of Don Pasquale. For reasons that remain a mystery, this year the company decided to mount its first-ever production of the composer’s French farce, La fille du régiment. Talk about a lacuna better left unfilled.

As heard on Monday night, the decision to stage Fille now was not because the company had a stellar cast to dazzle listeners. Soprano Anna Christy’s small, slightly warbling voice did not quite fill out the demands of the title role. She had enough at the top for the high notes in most places, but there was little brilliance to the tone. Her best comic moment was in the singing lesson scene, and she had a convincing male swagger that could make one believe she had been raised by soldiers.

Tenor Alek Shrader was more charming, as the Tyrolean bumpkin who woos Marie, all awkward posturing and nervous energy. The high Cs were there in Tonio’s big aria in Act I (“Ah! mes amis”), where Shrader brought a sense of dorky energy to the character’s enthusiasm at joining the regiment, which helps explain why he is singing so high. Shrader’s legato line was not sweet enough to melt one’s heart when, in his Act II aria, he has to appeal to Marie’s supposed aunt, the Marquise of Berkenfeld.

Phyllis Pancella used her whisky-rough chest voice to comic effect as the Marquise, and Kevin Burdette provided a manic presence as Sergeant Sulpice, down to his raucous, Steve Martin-esque happy dance. Among the supporting cast, Judith Christin’s superciliously corpulent Duchess of Krakenthorp – white face, towering wig, booming disdain, outrageous Tcherman accent – was the most memorable.

Conductor Speranza Scappucci, in her company debut, kept the fast tempos crisp and the balances clear, but there were too many moments where singers rushed ahead of her beat. She gave appropriate space to beautiful solos on English horn and cello, and the overture’s opening horn solo and twittering piccolo bits seemed to excite the real-life birds in the Crosby Theater’s rafters into dialogue.

Christy and Burdette are part of the reunion of artists from Santa Fe Opera’s production of Menotti’s The Last Savage in 2011. That wacky staging’s creative team – set and costume designer Allen Moyer, choreographer Seán Curran, and director Ned Canty – had less to work with in this slender comedy, which they kept traditional but made handsome. Another revolving stage revealed the front and back of two sets: the Tyrolean village’s makeshift barricade, which does little to repel the French army in Act I; and the well-appointed manor house of Berkenfeld, filled with hunting motifs, in Act II. The action was framed by an old-fashioned proscenium arch, painted with mountain scenes.

Canty’s English adaptation of the spoken dialogue achieved its stated goal of filling out the motivation of the characters, but was laden with over-repeated gags about German pronunciation and other clichés. The backdrop of the Jemez mountains, multicolored by the cooperating sunset and left visible by the open stage, provided a fine Montagnard effect.

Rigoletto runs through August 28 and La fille du régiment runs through August 29 at Santa Fe Opera. santafeopera.org.

Charles T. Downey is a freelance writer on music and roving summer festival reporter. The rest of the year he lives in Washington, D.C., where he writes reviews for the Washington Post and moderates ionarts.org, a Web site on classical music and the arts.