Florida Grand Opera to open season with Levy’s great, neglected American tragedy

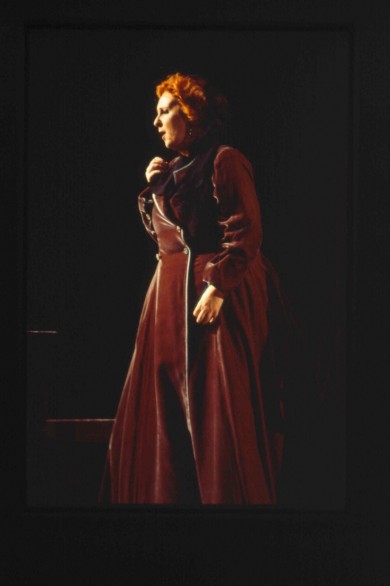

Lauren Flanigan will star as Christine Mannon in Marvin David Levy’s “Mourning Becomes Electra,” which opens Florida Grand Opera’s season November 7 at the Broward Center. Photo: Dan Rest/Lyric Opera of Chicago

Maybe the third time will actually be the charm.

To celebrate its inaugural season at Lincoln Center, the Metropolitan Opera commissioned two operas by American composers, one of them Mourning Becomes Electra by Marvin David Levy. Based on playwright Eugene O’Neill’s trilogy updating the ancient tale of the blood-drenched House of Atreus to 19th-century New England, the opera earned a fair number of raves at its 1967 world premiere. Critics particularly praised librettist Henry Butler’s deft distillation of O’Neill’s sprawling drama. The Met repeated it the following season, and it was produced in Germany in 1969.

Then Levy’s Mourning Become Electra disappeared.

Until 1998, when the composer overhauled it for Lyric Opera of Chicago, reducing the orchestra and shedding much of the dissonant harmonies that were considered mandatory for “serious” composers in the mid-1960s. That production was riveting. A spellbinding soprano, Lauren Flanigan, headed the cast as Christine Mannon, O’Neill’s Clytemnestra character, and Liviu Ciulei’s staging bristled with jagged New England Gothic gloom. Flanigan repeated the role in Seattle in 2003 and with the New York City Opera in 2004.

Then, once again, Levy’s opera disappeared.

Until November 7 when Florida Grand Opera presents Mourning Becomes Electra to open its 73rd season. Flanigan will reprise her role as the domineering matriarch of the dysfunctional Mannon clan. Ramon Tebar conducts a new production staged by Kevin Newbury. The opera will be performed Nov. 7 and 9 at the Broward Center for the Performing Arts in Fort Lauderdale and Nov. 16-17, 19 and 23 at the Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts of Miami-Dade County in Miami.

“People have to know how great this piece is,” said Flanigan. “That has to be the word about this piece. It is an exceptional, exceptional, exceptional modern American piece that has none of the odd, atonal trappings that a lot of pieces from this period had. It’s one of the greatest adaptations ever, I think, aside from Susannah by Carlisle Floyd, into an opera.”

When Levy received the commission from the Met, he was in his early 30s. A New Jersey native, he had been smitten with opera since his first visit to the Metropolitan Opera House at age 10. In the mid-1960s, he was barely past his graduate school days at Columbia University. But he had already written three well-received one-act operas and won a Guggenheim Fellowship. When the Met approached him, he suggested adapting Mourning Becomes Electra.

“I came up with the idea,” said Levy, now 81 and a Fort Lauderdale resident for decades,. “I never was really sure whether it was the play or O’Neill’s name [that appealed to the Met]. Because after all, I was a young unknown. How they were able to settle on me is still beyond me.”

The first challenge was shrinking O’Neill’s three plays, which run for a total of six hours,into a three-act opera. O’Neill transplanted the ancient Greek tale of the long-absent husband (Agamemnon), his unfaithful wife (Clytemnestra) their vengeful daughter (Electra) and murderous son (Orestes) into the cold, hard soil of post-Civil War New England. In their opera, Levy and Butler retained all of O’Neill’s fierce drama while adding their own, more eloquent spirit.

“It’s hard for me to say what the opera’s strengths are,” said Levy. “Everybody’s ears are different; we hear different things. I hear the lyrical moments. You’re condensing three plays into three acts. That’s a lot of condensation. The characters are boiled down to their essence, which is fine because it gives me a chance to expand on them.

“O’Neill himself knew that he was not a great poet. What was it that was missing? It was poetic eloquence. He didn’t have that, and that’s what I supply in the music.”

When Levy revised the opera for Chicago in 1998 he reduced the very large orchestra of 90 players to a more manageable 70. And he happily weeded out the dissonance he had woven into the original score. Lyricism was seriously out of fashion in the classical music world in the 1960s, and most young composers felt the need to write in the approved atonal, dissonant style. Levy, whose voice is essentially lyrical, had no trouble reworking the score.

“That’s what I wanted in the beginning and felt obliged not to do,” he said. “So it was like coming back to what I should have done in the first place.”

Getting the opera’s dramatic structure has been more vexing. In the original production, after poisoning her husband and learning of her lover’s murder, Christine Mannon commits suicide at the end of Act II. Levy agreed with critics who said the opera lost steam once Christine disappeared. He is still experimenting with how to solve that problem.

“It was two acts in Seattle,” said Levy, “but here we’re back to three acts. They all come back from the dead at the very end, which we didn’t do in Chicago. Christine is such a stage manipulator that you miss her when she’s gone.

“I view the work in a more affectionate way now–in some sense, like a grandchild. I worked on it a lot and it needed that. It’s a big, sprawling work and to get it down to a manageable size…They’re still diddling with it.”

He has been sitting in on rehearsals at Florida Grand Opera and is happy with the process so far. (Levy readily admits that he was eventually banned from rehearsals in Chicago and Seattle. “I was a pain in the butt,” he said with an unrepentant laugh.)

“I’m delighted with the cast,” said Levy. “And Lauren burns up the stage. She’s terrific. The more she pushes the voice the better she sounds. She loves the role. I didn’t know she was so fond of it. She really adores that role.”

Now in her early 50s, Flanigan has championed American composers throughout her career. She suffers from an inner-ear disorder that has limited her stage work in recent years, but she couldn’t resist the chance to reprise a role that fits her voice so well.

“Marvin’s language supports the vocal line,” said Flanigan. “In operas of that period of the 1950s and 1960s, the orchestra is like another character in the drama. Very often the vocal line and the orchestral line are not the same. That can be difficult for an audience. In this piece the orchestra is all about supporting everything that happens with the singing and what happens on the stage.”

American baritone Morgan Smith, who sings Adam Brant, a ship’s captain and Christine’s lover, also considers the role an exceptionally good fit. As a child growing up in the Northeast U.S., he spent a lot of time paddling on local rivers. In 2010 he created the role of Starbuck in Jake Heggie’s highly acclaimed adaptation of Melville’s Moby-Dick. Smith sang the small role of Peter in the Seattle production of Mourning Becomes Electra in 2003 and hoped to have a future chance to portray Adam Brant.

“The opera made a really big impression on me,” said Smith. “I thought this would be an amazing part to do some day. This is a guy who comes from very little means, and he managed to work his way up to become a ship’s captain. His background speaks a lot about his strength despite those circumstances. You sense, however, that when he’s on land he’s not quite as sure-footed.”

Flanigan has no doubt that Florida audiences will love Mourning Becomes Electra. She recalled being recognized at a local bank a few weeks ago. The young clerk said she “had always wondered” about opera, and Flanigan invited her to a performance.

“She said, ‘I don’t know, modern opera …’ Flanigan recalled. “I said, ‘Honey, believe me. At the end of this evening, you’re going to want to buy me a drink that’s how much you’re going to love it. You’re going to want to come again.’ It’s like Gone with the Wind.”

Levy has more mixed emotions about seeing his opera again, this time in his own hometown. He has suffered several health setbacks in recent years, has back problems and needs help getting around.

“It’s a happy occasion and a sad occasion,” he said. “Sad because I don’t think I’ll see it again at this point in my life. If it’s not done again relatively soon, how long can I last?”

Though Levy started his career steeped in opera, he never wrote another opera after Mourning Becomes Electra. Its neglect over the decades still stings.

“Because it was not performed, I never wrote another opera,” he said. “It really annoyed me no end that it was not picked up when I see all the trash that’s done.

“It’s not easy going.” Levy continued. “It takes such an amount of dedication to write an opera. It took me six years to get this right, and I’m still not sure it’s right. To me, pieces like this are always like a work in process.”

Marvin David Levy’s Mourning Becomes Electra opens Florida Grand Opera’s season November 7 and 9 at the Broward Center for the Performing Arts in Fort Lauderdale. The production moves to the Arsht Center for the Performing Arts in Miami November 16-23. fgo.org; 800-741-1010.