SFO overcomes backstage drama to offer a worthy “Dutchman”

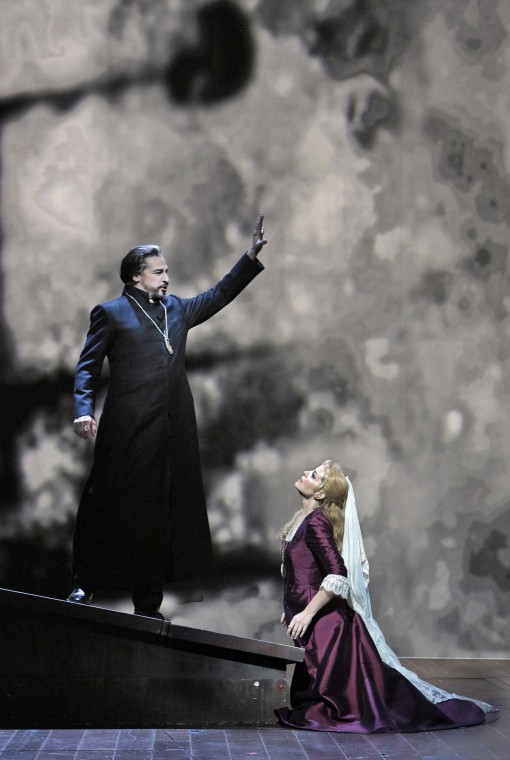

Greer Grimsley and Lise Lindstrom in San Francisco Opera’s production of Wagner’s “The Flying Dutchman.”

The drama in San Francisco Opera’s The Flying Dutchman began well before the first downbeat on opening night, when general director David Gockley fired director and set designer Petrika Ionesco and undertook a substantial reworking of the production.

In an unusually frank and detailed statement to the press, Gockley said he and his staff (led by assistant stage director Elkhanah Pulitzer) had scuttled 40 per cent of the scenic pieces, altered and enhanced the abundant projections, restaged the principals and eliminated the use of supernumeraries in various places.

It should come as no surprise, then, that this Dutchman emerges as something of a muddle, albeit a sometimes turbulent and propulsive one. This co-production with Belgium’s Opéra Royal de Wallonie was first mounted in Liege in 2011.

A good deal of Ionesco’s cinematic swagger – he cited Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind as an inspiration in a program note – remains. The title character, sung by the arresting bass-baritone Greer Grimsley, makes his first entrance when an enormous, space ship-like platform levers open to reveal a pulpy mass of pendulous red matter. The screens behind and around him are awash in surging waves, leaping fire and other semi-abstract projections. The sailors’ chorus, in Act III, takes on a zombie-like sheen as the singers freeze in bolts of blood-red light, apparently haunted by the sight of the Dutchman’s sails.

Gone is Ionesco’s notion of the opera as a projection of Senta’s fevered consciousness. Gockley excised the cemetery setting, complete with ghostly apparitions, of the heroine’s Act I scene in which she awaits the return of her father’s ship. Soprano Lise Lindstrom is freed to play a character instead of some freighted concept.

Lindstrom’s performance reveals both the strengths and liabilities of this production. With a voice that can sound decisively piercing one moment, float innocently the next and then take on a grinding nasal edge, the singer offers a Senta of multiple dimensions. She’s the single-minded artist who conjures the vision of her own destructive lover, the sweetly dutiful daughter and the willful young woman who throws over her loyal suitor for the deeper, destructive passion she feels for the Dutchman.

And yet for all the emotional range she finds vocally, there’s something stunted and constrained about Lindstrom’s acting. Perhaps she and the other performers still feel a little hypnotized and subsumed by Ionesco’s ideas. The hyperactive projections, wildly overused in the last act, have the effect of dwarfing the characters rather than expanding the opera’s fervent, tragic climax.

Grimsley makes a magnificent first impression under that mighty platform. Looking like an exiled gang member in his sleeveless black jersey, neck medallion and slicked-back hair (the fine costumes are by Lila Kendaka), he exudes a kinetic energy even when standing perfectly still. With the backing of conductor Patrick Summers’ spacious tempos and the orchestra’s dynamically plush sound, Grimsley unleashes a warmly thunderous expression of the Dutchman’s anguished search for the end to eternal wanderings. His suffering in this extended aria feels truly oceanic.

Bass Kristinn Sigmundsson, as Senta’s cheerfully callow sea captain father, serves as an entertaining foil. With his succinctly clipped vocal line and ingratiating manner, he engineers an engagement with daughter in exchange for the Dutchman’s booty. In a nice staging touch, the inept Steersman (nimbly played by tenor A.J. Glueckert, with a slightly frantic vocal push) hauls the chests of jewels offstage as Sigmudsson’s Daland cannily chuckles his way through his duet with the Dutchman he’s just reeled in.

The Spinning Chorus, done here in a lively if somewhat cliched presentation of the bustling womenfolk, gives way to the tender and moving scene of the huntsman Erik’s recitation of his dream. Tenor Ian Storey finds the opera’s haunting, fateful heart here, as he spins out the narrative of his own undoing as Senta’s patient suitor. Storey’s slightly pinched, constricted tone, specially at the upper reaches, feels just right. It’s the anguish of a man who can barely endure what he hears himself saying.

Lindstrom and Grimsley are less effective in their statically staged final duet. Their voices don’t mesh, hers is too hard-edged and his a little too recessively burnished. The drama is submerged at that point by the gush of foaming and glittering projections.

The Flying Dutchman is a work of “wild and somber beauty,” as Gustav Kobbé put it. There is wildness in this production, some of it musically and dramatically thrilling and some artificially applied. If the somberness shades into somnolence at times, this is nonetheless a serious and at times deeply moving production. Summers’ sumptuous but disciplined reading of the score, full of instrumental rages and murmurous calms, forms the steady floor.

Adversity is often a spur. The San Francisco Dutchman was refashioned under high pressure. It’s doubtful that anyone is fully pleased by these compromised results. But that also makes for some successful aspects that are all the more impressive and gratifying.

The Flying Dutchman runs through November 15. sfopera.com; 415-864-3330.