Adamo’s feminist “Mary Magdalene” opera is an unholy mess

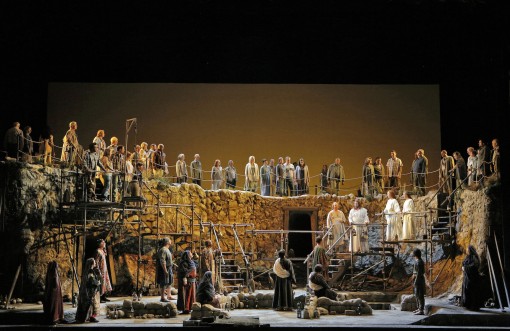

Nathan Gunn and Sasha Cooke in Mark Adamo’s “The Gospel of Mary Magdalene” at San Francisco Opera. Photo: Cory Weaver

As Jesus and Mary stopped their bickering and got married, and the interminable first act of Mark Adamo’s The Gospel of Mary Magdalene limped to its close in Wednesday’s world premiere at San Francisco Opera, crucifixion didn’t seem so bad a fate after all, at least for those seated in the audience. Anything to escape this hellish, three-hour show.

The opera world has seen some genuine turkeys over the years, but not since Anthony Davis’s Amistad, have I experienced such a hopeless operatic stink bomb as Adamo’s new work. Didactic, tedious, endlessly talky and mired in a numbing political correctness, The Gospel of Mary Magdalene is a disaster of biblical proportions.

Adamo’s third opera—following the great success of Little Women (1998) and the not-so-great success of Lysistrata (2005)—is inspired by the Gnostic gospels, particularly, the Nag Hammadi, which posits that rather being merely a penitent sinner, Mary Magdalene enjoyed a closer relationship with Jesus than the traditional canon suggests, as his closest disciple as well as either his mistress or wife.

The conceit is clearly a controversial one for those for whom Jesus’s divinity is a given. In his introductory program note, the composer said that, working off indications in these Gnostic gospels, Adamo “wanted to develop a credibly human original version of the story [without] its later magical embellishments. In such a new New Testament might its women characters speak as eloquently as its men?”

They might but they certainly don’t here. In Adamo’s revisionist retelling, Mary Magdalene is the principal figure, an adulteress who Adamo imbues with the highest moral authority and the real brains behind the Messiah. After Jesus, here Yeshua, saves her from the mob, and she shares his bed—mercifully only for a brief moment of writhing before the lights go down—they get married and she becomes his co-teacher, sharing the stage with him, correcting Yeshua and one-upping him with Adamo’s best lines (none of them very good).

Meandering and uneven, the score is cast in Adamo’s brand of souped-up lyric astringency with jagged brass and deafening percussion. There is an attractive post-coital aria for Mary in the first act but Adamo’s most consistent music comes after intermission, especially Mary’s affecting aria, “This is how I lose you.”

The devout will likely attack the opera for being insensitive and sacrilegious and there is plenty in the opera to offend believers. Yeshua here is illegitimate, a mama’s boy chauvinist with good intentions who’s just not as smart or sophisticated as the more worldly Mary and needs her to show him the way. Yeshua and Mary have sex, get married and teach the gospel together but those darn Romans get in the way of early female advancement by killing Yeshua and pushing Mary into history’s shadows. Crucifixions ruin everything.

It is not the provocateur elements that are the most critical problem, but the deadly endless dialogue and awe-inspiring banality of Adamo’s libretto. Despite the intent of the composer’s feminist gospel—-more noxious than Gnostic—rather than an inspirational figure, Adamo’s Mary comes off as a dour, humorless and self-righteous bore. Think Sandra Fluke without the charisma.

The libretto takes a barbed view of Jesus’s divinity and person, here stating he is illegitimate (the chorus repeatedly shouts “Bastard!” in what is supposed to be a humorous scene with a Pharisee). Most of Adamo’s leaden punchlines come at Yeshua’s expense, like “Nothing good ever came out of Nazareth.”

But it is the lousy writing that is even more off-putting than the lofty smugness and the posterboard Mary. The score abounds in lame couplets like, “I’m curious and charmed, and forewarned is forearmed” (repeated twice); Yeshua calls Magdalene, “Wisdom,” as befits her superior stature while she refers to him, slightingly, as “Nazarene.” Yeshua’s obsequious dialogue to the goddess-like Mary, “Be with me, Wisdom,” and her to him, “If I can make you female, perhaps you’ll understand.” Come on Jesus, don’t be such a wimp.

In this thankless role, Sasha Cooke as Mary sang with a flexible mezzo-soprano and deep chest notes. Still, her voice is somewhat colorless in tone, and her cool and remote stage presence failed to bring much humanity or sympathy to Adamo’s vision of Mary as feminist icon.

Though the deck is stacked against him in Adamo’s version of Jesus, Nathan Gunn somehow managed to emerge from the ashes Wednesday with dignity and artistry unscathed. In addition to making a handsome Yeshua, Gunn provided a non-tableaux-like figure, moving easily on stage, genuine and always human. He sang with a warm and flexible baritone and provided the finest vocal moments of the evening.

Instead of the mere denier of Jesus, in Adamo’s version, here Peter is a more of a composite character incorporating Simon Zealotes, encouraging Jesus to be more political against the Romans while harboring personal suspicions of Mary’s motives. Though Peter is the clear villain of the piece, he actually emerges as the most rounded character in the opera. William Burden’s muscular yet sweet-toned tenor and vivid and compelling characterization provided complexity and depth beyond the PC sloganeering.

Yeshua’s mother, here renamed Miriam, seems to exist primarily to present a kind of faux feminist sisterhood with Mary, warning her to run from Yeshua (“He’s deranged. Run from him. He will ruin you!”) and basically telling Mary she is too good for her mixed-up boy. Adamo gives Miriam much high-flying soprano passages, and though Maria Kanyova sang with commitment and intensity, her strident tone provided little pleasure.

David Korins’ unit set of a multilevel architectural dig was a striking visual with the story of Jesus and Mary acted out below in period costumes and a chorus of disaffected would-be believers in contemporary dress above. Christopher Maravich’s beautiful and resourceful lighting avoided monotony, and director Kevin Newbury moved the action as skillfully as possible considering the material he had to work with and the practical hurdles of the set.

Making his company debut, Michael Christie conducted with clarity and point, though his tendency to favor percussion and brass in balances too often swamped the singers.

Though the Adamo opera is a clinker, one still must give credit to David Gockley. At a time when many major opera companies are diluting their product with greatest-hits programming and Broadway musicals, San Francisco Opera’s general director is placing his faith in opera with three new commissions presented this year alone. With The Secret Garden receiving generally positive notices in March, let’s hope that Tobias Picker’s Dolores Claiborne arights the balance for 2013 SFO premieres in the fall.

And if you want a musical version of the gospels, stick with Jesus Christ, Superstar. The music is better and the show, much less pretentious.

The Gospel of Mary Magdalene runs through July 7. sfopera.com; 415-864-3330.

Posted Jun 20, 2013 at 3:42 pm by jsutton

Gotta agree. I was at the opening last night and my friend and I were astounded at how awful it was.

Posted Jun 20, 2013 at 4:33 pm by lunusualis

I was also at opening night and unfortunately have to agree with much of this review, although I do differ with you in your opinion of Sasha Cooke as Mary Magdalene — I thought she brought beautifully grounded dignity to her role, as well as a gorgeous, hall-filling sound. William Burden sang with remarkable diction and had an almost musical theater sound to his voice, perfect for the music. Nathan Gunn I found to be too often covered by the orchestra and with quite a wide and pitchy vibrato, although he did a lovely job acting his role. My admiration to everyone for doing what they could with the material. And bravo of course to SFO for bravely presenting new works, I love you for it and will continue to support all new initiatives (and I’m an under-30 audience member, for what it’s worth)!

Posted Jun 21, 2013 at 1:14 am by sburns

Thanks for telling it how it was. Wow, was that bad! I felt as though the composer was just trying to make Jesus (and the lot) look bad. There was no sense of a master, or a madonna for that matter, or any transcendant thinking. If this was what Jesus and Mary (the mother) were like it makes you wonder what the last 2000 years of history were all about and why billions of people worship someone like Michael Scott (the boss in “The Office”).

Posted Jun 22, 2013 at 2:06 am by Shean

I agree with pretty much everything but your praise for Gunn’s singing…it was not his best work, IMO. Thank you for such an honest and right-on evaluation.

“(the chorus repeatedly shouts “Bastard!” in what is supposed to be a humorous scene with a Pharisee)”, was sung by principle ‘seeker’ singers, not the chorus.

Posted Jun 22, 2013 at 7:21 pm by John

Your points are well taken and generally on the mark. If the Jesus and Mary as portrayed here are even close to accurate, why would anyone fall into the “believers” category. It strips away much of the foundation of Christianity as we know it. Nathan Gunns voice, more often than not, displayed a wide vibrato. I enjoyed Sasha Cook. I’ve been attending SFO for over 40 years. This was the first time that it was more important to me to get to the Bart station than it was to hear the ending of the opera.

Posted Jun 30, 2013 at 6:52 pm by Ray Gerba

I walked out during the intermission, only the second instance in 34 or 35 seasons as a subscriber that I have failed to remain until a works conclusion. A sojourn from no where to no where, I found little to redeem this misadventure. Consonant with Mr. Johnson’s review, the libretto was a sadly remedial endeavor utterly bereft of significance.