Met’s “Carmelites” closes season with devastating radiance

David Pittsinger as Marquis de la Force and Isabel Leonard as Blanche de la Force in Poulenc’s “Dialogues des Carmélites” at the Metropolitan Opera.

Photo: Ken Howard

An early decree of France’s revolutionary government concerned opera: the prohibition of public singing by castrati, seen as “unnatural” creatures fatally bound up with the depraved ancien régime. That opera was once a matter of urgent social concern is an astonishing idea today. The tidbit also hints at some basic antagonism between revolution and opera, in which the admittedly bloody birth of liberty, equality, and fraternity—think of Corigliano’s The Ghosts of Versailles or Giordano’s Andrea Chénier—tends to register as an unmitigated calamity.

The same moralists who censured the blade in service of virtuoso song used it to silence those they deemed enemies of the revolution, among them sixteen Carmelite nuns who in July 1794 sang hymns as they went to the guillotine at Paris’s Barrière de Vincennes. That episode inspired Francis Poulenc’s shattering opera Dialogues des carmélites, which received a superb revival Saturday afternoon at the Metropolitan Opera.

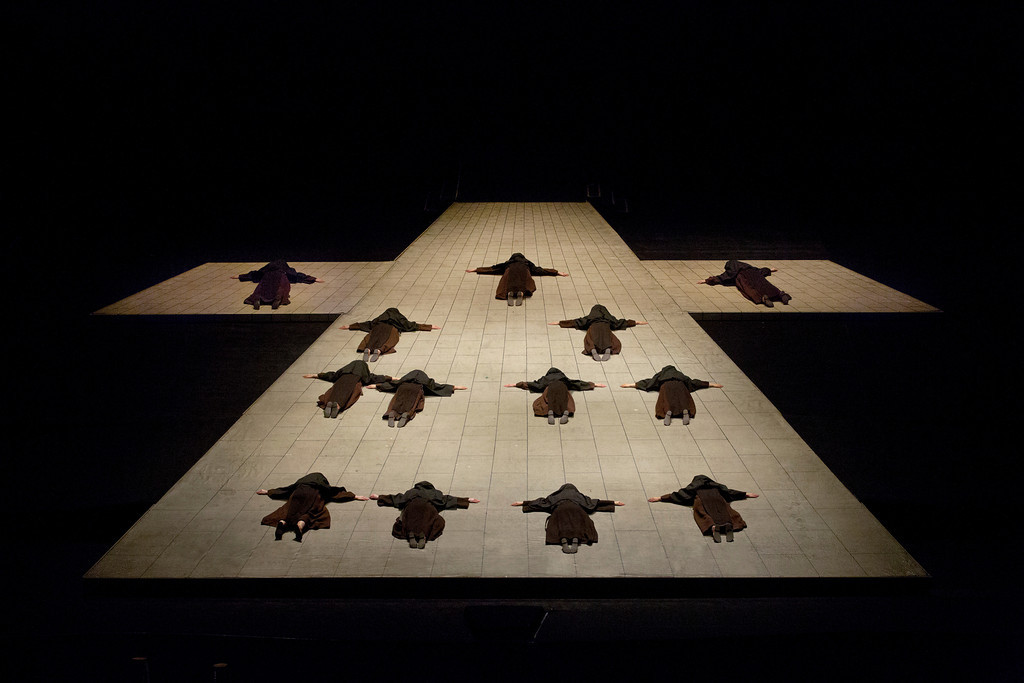

John Dexter’s austere 1977 production, now staged by David Kneuss, remains one of the company’s proudest achievements. The curtain opens to several moments of stillness and silence: nuns lie prostrate on the ground, their arms outstretched, as if taking upon themselves the suffering of the crucified Jesus. David Reppa’s unit set is itself a huge white cross set against a yawning black void; no-frills panels are lowered and raised to suggest a convent grille and interior spaces, and Jane Greenwood’s period costumes are handsome and unobtrusive. The staging is in every way a reproach to the largely glitzy, soulless productions that have reigned at the Met in recent seasons, and a helpful reminder that even in opera, the most over-the-top of art forms, sometimes less really can be more.

This revival of Dialogues does have one major flaw: it is sung in French by what looks to be an entirely Anglophone cast, even though Poulenc wished for the opera to be performed in the vernacular. Its 1957 world premiere at La Scala took place as Dialoghi delle Carmelitane, and the Met in seasons past has given it in English. Though most cast members on Saturday might have been singing in Etruscan for all that one could tell, their passion and musical excellence made up in part for the overall dearth of verbal zing.

Patricia Racette, Blanche in the Met’s 2003 revival of Dialogues, this season takes on the role of the new Prioress, Madame Lidoine. There can be a pronounced flutter to her highest notes, but Racette is a Prioress of steely strength and spiritual radiance, heartbreaking in her blessing of her charges after their death sentence is read and in her tender concern before she leads them to the scaffold. A flame seems to burn in her voice as she intones the Salve Regina, one that grows ever more incandescent as her fellow nuns take up the hymn, then slowly peters out as the implacable rasp of the guillotine sounds again and again.

Isabel Leonard, the winner of the 2013 Richard Tucker Award, was an intense and graceful Blanche de la Force, both proud in bearing and palpably fragile and skittish. The dark luster of her voice was most admirable in her hymn, the closing verse of Veni creator spiritus, and though the guillotine abruptly silenced her invocation of “world without end,” Poulenc’s luminous final measures as played by the Met orchestra told of mourning leavened by the mysteries of faith and hope.

Her tone pearly and bright, her manner blithe yet shot through with underlying gravity, Erin Morley as Sister Constance was the vocal star of Saturday’s Dialogues; her voice and Leonard’s blended and intertwined to exquisite effect in the prayers for the dead in the first scene of Act II. Felicity Palmer as the Old Prioress, Paul Appleby as an ardent Chevalier de la Force, and David Pittsinger as his father the Marquis all showed an admirable grasp of French style and sang beautifully; Palmer’s rendering of the Prioress’s final agony induced terror without resorting to scenery-chewing.

Elizabeth Bishop brought fervor and a lush, firm sound to the role of Mother Marie, and Mark Schowalter was a deeply sympathetic chaplain. Richard Bernstein, swaggering and ever inky of tone, and Patrick Carfizzi stood out among the splendid supporting players, who included Eduardo Valdes, Paul Corona, Mary Ann McCormick, Scott Scully, and Jane Shaulis.

The remaining Carmelite nuns—Christina Thomas Anderson, Stephanie Chigas, Catherine Choi, Mary Hughes, Sunghe Lee, Kathleen Mangiameli, Rosemary Nencheck, Ann Nonnemacher, Amanda Osorio, Belinda Oswald, and Sara Stewart—sang well and faced death each in her own way, some striding forward with gladness and arms outstretched, as if greeting a long-awaited friend, some brisk and no-nonsense, others cowering but comforted and encouraged by a sister.

In the thirty-odd years since Dialogues joined the Met repertory, Poulenc’s opera has been entrusted to such outstanding French stylists as Michel Plasson and the lesser-known (but unique and unforgettable) Manuel Rosenthal. On Saturday Louis Langrée led a performance to rank with the very best. His conducting had a keen pulse and an unerring sense of proportion; he conjured layer upon velvety layer of sound for the restless music associated with Blanche’s fears; and he summoned weirdly swooning and perfumed strains for the Ave verum corpus hymn in Act II, a meditation on Christ’s suffering human body.

That detail encapsulates some of the many paradoxes at the heart of this opera. It examines the mystery of the Incarnation, of God made vulnerable flesh. It tells of women living under a vow of obedience condemned as seditious threats to their society. It is a song of wholehearted Catholic faith sung by a composer who was gay and whose church taught (and teaches) that his love was disordered. And on Saturday, in these days of ever-more-prurient amusements, it brought a motley New York audience to rapt, pin-drop silence.

Francis Poulenc’s Les Dialogues des Carmélites repeats on May 9 and closes the Met’s season on May 11. metoperafamily.org; 212.362.6000.

Posted May 09, 2013 at 2:52 am by Philip Gossett

It must be a simply wonderful performance. Thank you for this. A young scholar in France has jugt discovered Poulenc’s own vocal score of the opera, with many changes, i his own hand, that he made in the vocal lines for the Milanese prmiere. Virginia Zeani (the original Blanche, now retired from Indiana University) apparenttly confirmed that what they sang in the 1950s was not at all what is printed today in the Ricordi score,but something very different.Yet no one seems to know this. Certainly the Met doesn’t have a clue.