Fleming soars in premiere of new song cycle at Carnegie Hall

Renee Fleming gave the world premiere of “The Strand Songs” by Anders Hillborg with Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic Friday night at Carnegie Hall.

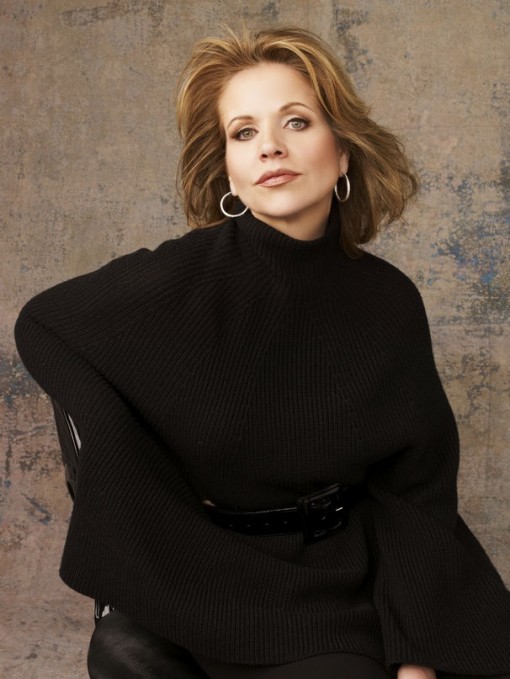

Last night Renée Fleming gave the next-to-last concert in her Carnegie Hall “Perspectives” residency, part of a season that had a retrospective feeling to it. At the Metropolitan Opera, she reprised her celebrated portrayal of Desdemona in Verdi’s Otello, and at Carnegie Hall (and Lyric Opera of Chicago), she revisited a role she created, Blanche Dubois in André Previn’s A Streetcar Named Desire. She ramped up her visibility as Lyric Opera creative consultant, suggesting that the transition to her post-singing career is gaining momentum, and Opera magazine reported that her Covent Garden farewell is already scheduled for the 2016–17 season.

And yet in concert with the New York Philharmonic under Alan Gilbert on Friday, Fleming sang beautifully, looked as regal as ever in billowing layers of midnight-blue chiffon, and showed no interest in resting on her laurels. Instead, she reaffirmed her commitment to living music and artistic growth by giving the world premiere of The Strand Songs by Swedish composer Anders Hillborg, a work co-commissioned by the Philharmonic and Carnegie Hall.

The four songs in the cycle are based on poems by Mark Strand, a former U.S. poet laureate whose collection Blizzard of One won a 1999 Pulitzer Prize. While Hillborg’s settings have a moderate tessitura, stressing verbal clarity and largely eschewing vocal pyrotechnics, these qualities seem less a concession to a veteran singer than an apt response to Strand’s work, which is plain in diction but dense and challenging in its imagery. The uneasy hiss of high strings weaves its way through all four songs, in which the poetic “I” tells of “whispering” and “murmuring” nights, angels “chewing their tongues, not singing,” and “the flesh of clouds.” Hillborg’s orchestra includes a sort of glass harmonica (four wine glasses), an instrument notoriously hard to hear in modern concert halls, but whose ethereal sounds (and age-old bond with derangement and the music of the spheres) seemed to infuse the entire score.

That last image, fusing the wispy and the carnal, exemplifies the paradoxes at the heart of Strand’s verse. “The Black Sea,” the first song, in which “dark” becomes “desire” and “desire the arriving light,” inevitably brings to mind Tristan und Isolde, though Hillborg’s cycle begins and ends in E-flat, the key of watery depths in Wagner’s Ring der Nibelungen, and his gently declamatory vocal writing has nothing Wagnerian about it. Early on Fleming indulged in her familiar habit of overplaying single words (“night,” “sky,” “stars”) and pulling vocal taffy but quickly relaxed, her voice soaring over the groaning brass at the song’s climax. Her way with the cycle’s most overtly erotic passage—“you leaning down and putting / your mouth against mine” in “Dark Harbor XX”—was all the more telling for its chaste understatement, and she spun a luminous piano in the song’s closing phrases.

Fleming summoned bluesy tones and Hillborg a Bernstein-esque bustle for “Dark Harbor XXXV,” with its heavenly creatures “down by the bus terminal, hanging out.” Shards of bone-rattling, metallic noise broke through the score for “the pure erotic glory of death without echoes,” and singer and composer made an abrupt, heart-stopping end for “kisses blown out of heaven, / melting the moment they land.” Juxtaposing “a prodigal / overflowing of mildness” with blinding canicular light and happiness with “terrible omens of the end,” “Dark Harbor XI” is the most unsettling of the four songs, its airy arpeggios giving way in the closing measures to slithering strings and dreadful tone clusters. Diva, composer, poet, maestro, and band received long and rapturous ovations at the end of the twenty-odd minute cycle.

Two warhorses made up the rest of the skimpy program (a scant hour and a half of music), which offered few surprises but did have the virtue of consisting solely of texted and descriptive works—an implicit rebuke to the lingering notion of music as a “transcendentally-significant-yet-meaningless terrain,” to quote musicologist Susan McClary. Gilbert and his players worked wonders with Ottorino Respighi’s Fountains of Rome, summoning a pulsing, perfumed cloud of sound shot through with whistling winds and rustling strings for dawn at the Valle Giulia, bold drumrolls and brassy grandeur for the Trevi Fountain at noon, and ravishing soft playing by the winds and low strings for the sunset at the Villa Medici.

In Maurice Ravel’s familiar orchestration of Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition,Gilbert and the Philharmonic did not quite match the razor-sharp precision and Technicolor glory of, say, the Philadelphians under Muti or Stokowski, but their performance was efficient and enjoyable. The brass playing was majestic throughout; the faux-galant filigree of the writing in the Tuileries section was fittingly insouciant; the slightly untidy scramble of the unhatched chicks heightened the whimsy of their dance; and the Kiev gate loomed grandly with massive yet cleanly drawn layers of sound.

Renée Fleming’s “Perspectives” series at Carnegie Hall concludes on May 4, when she performs with pianist Jeremy Denk, the Emerson String Quartet, and others:www.carnegiehall.org or 212.247.7800. Alan Gilbert leads the New York Philharmonic at Avery Fisher Hall tonight in music by Mozart and Bruckner: www.nyphil.org or 212.875.5656.