Glorious singing and striking new production highlight Met’s “Un ballo”

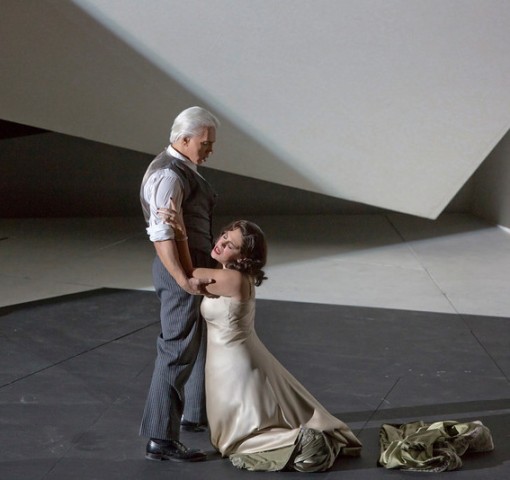

Sondra Radvanovsky as Amelia and Marcelo Álvarez as Gustavo in Verdi’s “Un Ballo in Maschera” at the Metropolitan Opera. Photo: Ken Howard

As Giuseppe Verdi’s 2013 bicentennial approaches, many listeners still think of him as a mirthless master visited by the comic muse only for Falstaff and the early and ill-fated Un giorno di regno. Yet laughter glints in many Verdi scores—Ernani, Macbeth, Rigoletto, and La forza del destino among them—and it permeates his 1859 masterwork Un ballo in maschera, presented in a new production by David Alden at the Metropolitan Opera Thursday night.

Indeed, Julian Budden called Ballo Verdi’s Don Giovanni, an essentially comic opera with edges charred by hellfire. Ballo teems with the strophic songs and saucy dance rhythms of opéra comique and the Parisian boulevard theatre. And like Mozart’s dramma giocoso, it turns on maskings and unmaskings and depicts a morally suspect nobleman whose all-consuming hunger for life prompts him to face death willingly, even defiantly.

Alden’s staging, while flawed, did not deserve all of the angry boos that rained down during the opening-night curtain calls. It takes place in the early twentieth century, with a swerve into the age of Mozart (evoked by Verdi’s sublime mazurka) in the final scene. The director grasped Ballo’s hybrid and meta-theatrical nature. The opening scene’s giddy stretta, Dunque, signori, aspettovi, played out like a Busby Berkeley spectacular, with high kicks and tumbling waiters and brandished coupes de champagne, making the crashing chords and sepulchral clarinet tones that follow in the soothsayer Ulrica’s den all the more chilling by comparison. The conspirators whose sardonic guffaws end Act II peered at the unveiled Amelia through opera glasses as they sang so mistakenly that a tragedy had become a comedy.

The final ball, too, was superbly staged. A burst of applause usually greets the real-time scene change from Gustavo’s study to the masquerade where he will die. At the Met, though, Verdi’s whirlwind of modulations swirled as black-clad revelers and angels of death appeared to seep through the edges of the ballroom’s mirrored walls and lustrous floor like so many inky puddles reaching out to swallow the king. Brigitte Reiffenstuel’s costumes recalled Alexander McQueen’s disquieting feathered gowns, and Adam Silverman’s lighting here cast mother-of-pearl reflections that echoed and exploded the moiré patterns seen in Paul Steinberg’s designs for Acts I and II. The production was haunted by a painting of the mythological character Icarus, whose wings of wax and feathers melted when, undone by hubris, he flew too close to the sun.

All of that said, Alden’s work was not uniformly apt or inspired. Steinberg’s sets, most with skewed angles in the style of film noir, gave this Ballo an excessively sinister edge. (Shimmering with irony, Verdi’s opera is “comic” perhaps most of all in its bloody final scene, when the dying Gustavo forgives his murderers and the onlookers in a blaze of musical light liken his mercy to divine grace.) Gustavo and Amelia sang their wild, guilty love duet from opposite ends of the stage, barely touching or even looking at each other.

Regie clichés abounded, including bureacrats in bowler hats à la Magritte and writhing dancers indulging in vaguely sadomasochistic antics. (The twitchy choreography is by Maxine Braham.) The lighting shifted repeatedly and to no discernible end during the scene at Renato’s house, set in a pitiful black-and-white box that may have been a ham-fisted attempt at representing a cuckold’s primitive sense of justice. The scene on the heath brought to mind Laurent Pelly’s aggressively ugly Met Manon, and Ulrica’s clients seemed to be the witches from Adrian Noble’s Macbeth wandered into the wrong opera.

Musically this Ballo offers much to admire. As Renato, Gustavo’s friend-turned-mortal-foe, Dmitri Hvorostovsky sang gloriously and with greater discipline than I have ever heard him summon in Verdi. Alla vita che t’arride, plodding when performed by lesser artists, unfolded with grace and urgency. The baritone saved his bluster for the vengeful bits of Eri tu and in the rest of that great and multifaceted aria spun insolently long, tense, slow-burn phrases, ending the scene in heartbreaking manner with his face buried in a wrap left behind by Amelia.

Hvorostovsky and Sandra Radvanovsky have white-hot chemistry on stage, making Renato’s change of heart about the king he had loyally served fully credible. As Amelia, Radvanovsky needed to enunciate more clearly, and her voice under pressure sometimes turns sinewy, but her dark sound and phosphorescent upper register are ideal for the music of Verdi’s tormented heroine. The marital love that so palpably still simmers between this husband and wife made her desolate, pleading Morrò, ma prima in grazia devastating, and her voice rode the climaxes of the love duet and the opera’s driving ensembles with thrilling ease.

Marcelo Álvarez, too, turned in the best singing of his Met career as Gustavo. His odd yelp and inaudible dips into the baritone range in Di’ tu se fedele were more than offset by his imaginative and deeply felt way with the text throughout this long, complex, and relentlessly challenging role. He mustered a honeyed sound for the “sweet songs” evoked in Gustavo’s barcarole and a rapturous pianissimo for his repetition of M’ami in the love duet. He admirably, and in accordance with the composer’s express wishes, did not laugh during È scherzo od è follia but instead made the notes and words tell of merriment, and he embraced his love and his death with a heedless, generous, and irresistible abandon fully worthy of Verdi’s greatest and most deeply humane character.

Dolora Zajick’s best singing came in the fiery heights and not the sulphurous depths of Ulrica’s music. Kathleen Kim brought something of the world-weary, androgynous allure of Marlene Dietrich in Morocco to her nimble, brightly sung portrayal of the page Oscar. The lush, ebony tones of Keith Miller’s Ribbing stood out among the cast’s strong supporting players, including David Crawford, Mark Schowalter, Trevor Scheunemenn (a genial Silvano), and Scott Scully.

The Met’s chorus under Donald Palumbo worked their customary magic; Fabio Luisi’s conducting and the alert playing of the Met orchestra elucidated the iridescent, multi-layered colors of this miraculous score. Like Dante, Verdi wrote a comedy that examines matters grave and dark. He showed that “all the world’s a stage” in the manner of his idol Shakespeare. In a similar way to Mozart in Le nozze di Figaro, he sang of the balm of human mercy and unfurled a dance like the one in Visconti’s The Leopard, piercingly beautiful because it is doomed to die. While the Met’s new Ballo is not a perfect two-hundredth birthday gift for Verdi, it brings us some of his opera’s fathomless riches, and for this we can be grateful.

Un ballo in maschera runs through December 14. Stephanie Blythe takes over the role of Ulrica on November 27. Ballo will be shown as part of the Live in HD series on December 8. 212-362-6000; metoperafamily.org.

Dmitri Hvorostovsky as Count Anckarström and Sondra Radvanovsky as Amelia in Verdi’s “Un Ballo in Maschera.” Photo: Ken Howard