New York Philharmonic to close season with Stockhausen’s tri-orchestral “Gruppen”

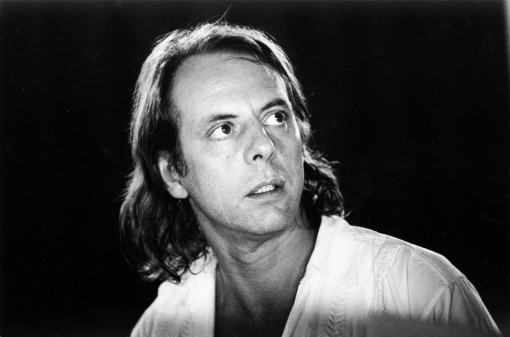

Karlheinz Stockhausen's "Gruppen" will be heard Friday night at the Park Avenue Armory with Alan Gilbert, Matthias Pintscher and Magnus Lindberg conducting the New York Philharmonic. Photo: Bernard Perrine, 1972.

On a recent afternoon in New York City’s Park Avenue Armory, Matthias Pintscher stood squinting amid the high-pitched whirr of drills and the mechanical hum of two yellow forklifts. The German composer and conductor was mentally calculating the distance between the three temporary stages that were being set up around a central circular seating area as if to form an enormous radiation hazard symbol. “We are going to have to see each other across a huge distance!” he exclaimed with a short laugh that may have been designed to dispel fear.

On Friday Pintscher will join New York Philharmonic music director Alan Gilbert and Finnish composer-conductor Magnus Lindberg in leading the New York Philharmonic in Gruppen (“Groups”), a monumental work by Karlheinz Stockhausen and one of the most viscerally exciting and pleasurable works of Modernist music. The 25-minute tour-de-force for 109 musicians divided into three spatially separate ensembles, each with its own conductor, is the centerpiece of the orchestra’s “Philharmonic 360@” program of spatial music with which it celebrates the end of the season.

“Gruppen is an iconic work,” says Gilbert. “It’s a piece that’s specifically conceived on the premises of exploiting a physical space and it’s the sort of piece that really has to be experienced live.”

First performed in 1958, Gruppen is built out of blocks of serially constructed musical material that is passed around among the three ensembles who much of the time play at different speeds, like interlocking cogwheels of different sizes. For the conductors, the challenge lies in both leading their respective ensemble and keeping an eye on their colleagues across the hall in order to send and receive visual cues — hence Pintscher’s concern with sightlines.

For the audience – especially the ones seated on the floor in the midst of the three orchestras, as Stockhausen intended — the experience becomes one of a stereophonic rollercoaster, with waves of sound passing through and around them. “It’s all about the flow,” says Pintscher. “As in all great works, the complexity of the structure is not apparent to the listener. It comes out sounding very organic. It’s a very sensuous piece.”

For Gilbert, Gruppen must have seemed an obvious choice of repertoire when planning a Philharmonic concert in the Armory, but he is rounding out the program with a mix of the fitting and the counter-intuitive. Rituel by Pierre Boulez, a work made up of filigree textures created by eight spatially separated ensembles, will now sit alongside Charles Ives’ The Unanswered Question, in which the interaction of stylistically different musical idioms takes on a philosophical dimension.

And then there is the Act 1 Finale of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, a typically Mozartian display of wit and skill, in which one of the ensembles can be heard tuning up on the open strings while another plays dance music, all blending into a harmonious whole. “The scene is a party and there are three different dance bands playing at the same time and Mozart, in his inimitable genius way, manages to compose it so that their three different pieces sound great together,” says Gilbert.

In Gruppen, the bravura act is mostly in the hands of the conductors, whom Stockhausen transforms into virtuosic performers locked into an intricate choreography. Lindberg, who, like Pintscher has conducted Gruppen before, says the spatial interplay combined with ever-changing speeds mean that even a flickering loss of attention can spell disaster. “I always thought this is what it must feel like to be a professional ice hockey player,” he says.

As composers, Pintscher and Lindberg each have an additional practical interest in the plasticity of sound. Lindberg’s Kraft, which the New York Philharmonic performed last season at Avery Fisher Hall, involves musicians distributed throughout the auditorium, creating tracks of sound through space that gradually evoke a three-dimensional architecture. “I wrote Kraft in 1983-84 when I was living in Berlin and it was very much influenced by Stockhausen,” says Lindberg.

Pintscher, who most often writes for symphony orchestra, says he is always looking to exploit the spatial tensions and acoustic pathways within a large instrumental ensemble. At the same time, his work as a conductor provides a certain historical perspective, as when he recently conducted a concert of works by Giovanni Gabrieli, one of a number of early seventeenth-century Venetian composers who reveled in monumental works for multiple vocal and instrumental ensembles. The effect on the listener, says Pintscher, is ultimately the same in spatial music of any era: “It’s an embrace.”

The New York Philharmonic performs Stockhausen’s Gruppen 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday at the Park Avenue Armory. Both performances are sold out but turnback tickets may be available. Also the concert will be streamed in a free webcast on nyphil.org beginning July 6.