A double shot of Glass at Lincoln Center with a belated NY Philharmonic debut

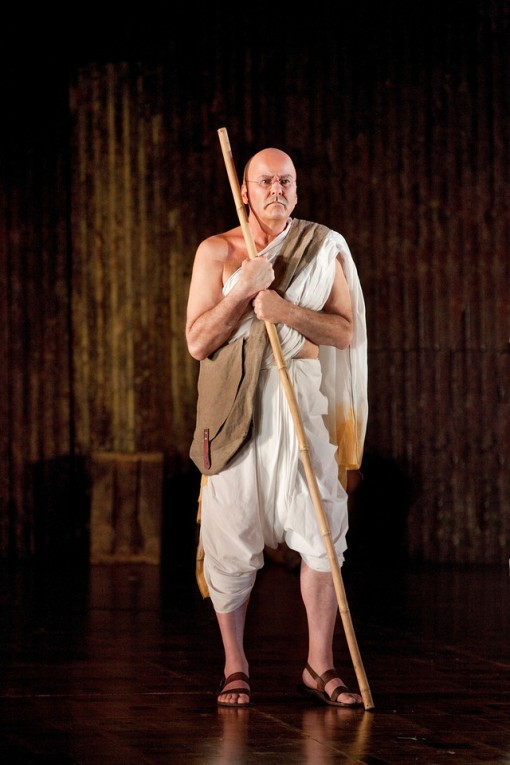

Richard Croft as Gandhi in Philip Glass's "Satyagraha" at the Metropolitan Opera. Photo: Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera

It took Philip Glass more than 50 years to see his music played by the New York Philharmonic, but then, he never did become the most influential — and divisive — composer in America by relying on the support of the establishment. “If there’s no room for you at the table, make up your own,” he once told a young composer fresh out of college. This week, Glass was guest of honor at Lincoln Center in a double bill that heralds a flurry of similar tributes celebrating his upcoming 75th birthday in January.

On Wednesday and Thursday, the Philharmonic screened Godfrey Reggio’s 1982 film Koyaanisqatsi to a live performance of Glass’s hypnotic score in which the Philharmonic joined forces with the composer and his eponymous ensemble. It was the first time the orchestra ever played music written by Glass. On Friday, the Metropolitan Opera reprised its mesmerizing 2008 production of Satyagraha (1980), Glass’ opera about Gandhi’s early years in South Africa.

Both are essentially works of political activism. Koyaanisqatsi – the title is taken from a Hopi word translated as “life out of balance” — is a wordless indictment of Western society. Its anxieties, including the pollution of the environment, overpopulation, nuclear armament, and the dehumanization of big-city life, are the same ones coloring today’s discourse. And against the backdrop of the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street, Satyagraha (Sanskrit for “truth force”) offers a message of nonviolent civil protest that has lost none of its power. But while the frenetic music and imagery of Koyaanisqatsi at times feel manipulative, Satyagraha opens up a vast, contemplative space in which the listener is free to think, dream or meditate. In the magically playful production by director Phelim McDermott and set designer Julian Crouch, it continues to reveal itself as a masterwork of modern opera.

To appreciate it as such, it helps to adjust expectations. Not much happens. The words are in Sanskrit. The music is built on repetitions of simple motifs; arpeggios and scales, for the most part. Gandhi’s Protest aria consists of a single note, repeated over and over in a lilting stutter. But set against a tapestry of undulating strings and a falling motif in the winds that echoes the brooding opening line of Mozart’s Symphony No. 25, that note can become achingly expressive. It certainly did in the hands of tenor Richard Croft, who returned to the role of Gandhi he sang to critical acclaim in 2008.

Doing so requires him to rein in his naturally lyrical, expansive style of singing, but the effect is not that of a voice reduced, but rather one purified. Producing each note seems almost like a private act – song as prayer rather than communication. The sense of other-worldliness perfectly fits his character. His final aria, sometimes called Evening Song, was deeply touching. Set to a text from the Bhagavad Gita which predicts Krishna’s coming reincarnations to “take a visible shape and move a man with men for the protection of good,” it consists of a simple Phrygian scale, repeatedly rising over pulsating strings. Some tenors feel compelled to endow each repetition with a different inflection or intensity, but Croft kept his even, filled with love and wonder.

In an opera that takes as its subject the negation of self and the virtue of collaborative work, it seems almost inappropriate to single out particular members of the cast. Kim Josephson brought a warm, round baritone to the role of Mr. Kallenbach. Bradley Garvin as Prince Arjuna and Richard Bernstein as the blue-faced Lord Krishna sounded glorious in the Act I trio with Mr Croft. The women were led by Rachelle Durkin as Miss Schlesen, whose florid soprano injected a welcome note of human passion into a world of self-abnegation.

The Metropolitan Opera Chorus took on what must be one of the most arduous parts in the repertoire with impressive discipline. In “Confrontation,” the first scene of Act II, its members function both as braying fools, praising the pursuit of wealth, and as jeering South African whites, taunting and menacing Gandhi and Miss Schlesen. The vocal part consists of a kind of stylized staccato laughter track that requires rhythmic precision, but also subtle shifts in volume and phrasing. The Met chorus made it sound easy, evidently trusting in conductor Dante Anzolini, whose direction was a model of clarity. The orchestration for Satyagraha consists only of strings and winds, with the subtle support of electric organ. The resulting sonorities sometimes make the piece feel like a chamber opera.

A completely different sound dominated the New York Philharmonic’s performance of Koyaanisqatsi, where the synthesizers and amplified voices of the Philip Glass Ensemble were overlaid with powerful masses of brass. It was a role the Philharmonic seemed to relish, even if there was sometimes a sense of the two ensembles competing for territory. Michael Riesman conducted with reptilian calm despite some frenetic tempi and the Collegiate Chorale courageously took on some very uncomfortable vocal writing. As exciting as the fusion of image and sound was, there was something odd about the choice of a film score for Glass’ New York Philharmonic debut. With a bit of luck, they’ll play one of his symphonies — how about No. 6, Mr Gilbert? — before the composer turns eighty.

Satyagraha runs through Dec. 1. metopera.org

Posted Nov 07, 2011 at 12:20 pm by Proman

Great review. One quick comment, though.

What do you consider the beginning of Glass’ career?

The more than “Fifty years comment” implies that he started before 1961 and that seems a bit wrong. There are pieces that date to that time, I am sure, and a decent as some of them are, these are pre-student works. I’d say crica 1966~67 where he started writing for his ensemble would seem like a better starting point.

And as for a symphony that needs to be performed by NY Philharmonic, how about the glorious #8?