Philharmonia Baroque’s “Orlando” makes for an evening of Handelian delights at Ravinia

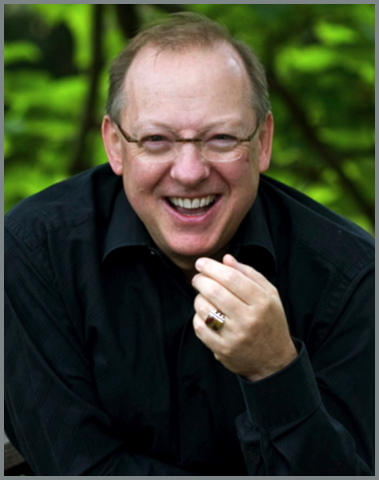

Nicholas McGegan led the Philharmonic Baroque in a performance of Handel's opera "Orlando" Thursday night at Ravinia. Photo: Randy Beach

The Handel opera revival has had its share of ups and downs as a repertoire long neglected became slowly but surely unearthed and reanimated.

In the case of Handel’s Orlando, there was more than a two-century silence after its initial ten 1733 performances. It wasn’t until the mid-20th century that the work was resurrected in modern performance.

Lyric Opera presented Orlando 25 years ago as a vehicle for Marilyn Horne and — amazing as it seems in retrospect — Lyric’s first-ever production of a Handel opera. (Jon Vickers had performed the title role in a staged version of the oratorio Samson the previous season.) Chicago Opera Theater revived it in 2008.

The spectacular touring production of Orlando that touched down at Ravinia’s Martin Theatre Thursday night celebrates the 30th anniversary of the San Francisco-based Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, which music director Nicholas McGegan has been leading for 25 of those years.

To hear a first-rate period-instrument performance of a Handel opera in an intimate venue with a large cast of singers who are true masters of the period technique that these works require is nothing short of a revelation.

From the opening notes, McGegan gave off a smile that remained in place for the entire performance, and, through the final chorus some three-and-one-quarter hours later, the fusion of 18th-century music and drama was a sheer delight at every turn.

So often Handel operas and oratorios are performed in an episodic manner, i.e., with clear demarcations between recitatives, arias, duets, ensembles, et al, but not here. There was an overall arc and buildup of momentum, tension and release that revealed that Handel was as much a dramatic master on a large scale he was in smaller things.

South African countertenor Clint van der Linde made a compelling Orlando, not only tossing off the runs and trills of the role like child’s play at breakneck speed, but giving a genuine masculinity to both his sound and portrayal.

Whether being outraged and angry or tender and poignant, you had real feeling for this hero. His tender, almost lullaby-laden Quel dolce liquore — with expressive double violin accompaniment — was as passionate as his fiery Fammi combattere or his introspective Cielo! Se tu il consenti. And his drawn out sung sighs in Che del pianto ancor nel regno were exquisite.

Russian-American soprano Yulia Van Doren, replacing the originally announced Susanne Rydén as the apron-clad shepherd girl Dorinda, brought pathos and three dimensions to what is often a thankless role dramatically. She was no less excellent vocally. Her cadenza in O care parolette was a particular highlight and her Se mi rivolgo al prato was truly poignant yet never sagged under its own weight.

Canadian soprano Dominique Labell as the queen Angelica served up vocal fireworks on cue for Non potrá dirmi ingrate and made for a regal presence with her mannerisms, purple gown and jewelry.

British mezzo-soprano Diana Moore made a delightfully shameless seducer in the trouser role of Medoro, particularly in Se il cor mai ti dirà and Verdi allori, sempre unito where she effectively incorporated a tad of expressive vibrato.

Dramatically, German bass-baritone Wolf Matthias Friedrich nearly stole the show in his scenes as the magician Zoroastro, evoking a sense of magic and mystery with only a long black coat and his wonderfully expressive hands and eyes.

McGegan and the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra were formed in an oval directly behind the singers surrounding two harpsichords with McGegan off to the right side sometimes conducting, sometimes playing harpsichord accompaniment.

There are huge benefits to playing together for a quarter of a century: so much was communicated with so little means, and the transparency of lines were crystal clear, the ensemble tight and balances between orchestra and singers always showing each to equal benefit. Even the continuo sequences during recitatives were so creatively rendered that they never felt like a wind-up to an aria as they so often do, but an integral part of the music drama, which by 18th-century standards, they were.

Tempos were brisk, to be sure, but never rushed. The orchestra was always delightfully just ahead of the beat and rendered Handel’s music with the lyrical flexibility and pulsating swing that showcases the style to its best advantage.