For composer David DiChiera, his “Cyrano” is a romantic dream come true

Leah Partridge as Roxane and Marion Pop in the title role of David DiChiera's "Cyrano," which opens April 23 at Florida Grand Opera. Photo: John Grigaitis

In a long career in opera, David DiChiera has placed a lot of bets on likely losers.

For the location of his new opera house, he chose one of the least promising settings in urban North America: downtown Detroit. At a time when audiences seemed to want only Carmen, La Traviata and the rest, he set up a national initiative to encourage the creation and staging of new operas. And finally, in his 60s, he set out to write an opera of his own, flexing compositional muscles that he feared might have atrophied during his years of opera administration.

Today his Michigan Opera Theatre is one of the leading regional companies in the United States. The contemporary opera scene in the United States is bursting with new works, even in the current lowly economy. And DiChiera’s opera Cyrano, which opens April 23 at Florida Grand Opera, has turned into a hit, winning standing ovations and praise from some tough critics, impressed with the work’s authentic if traditional style. (While noting Cyrano’s unabashedly conservative idiom, Anne Midgette of the Washington Post wrote that “the music is melodious and tonal” and that the opera overall “is utterly sincere, and affecting: a love story that comes from the heart.”).

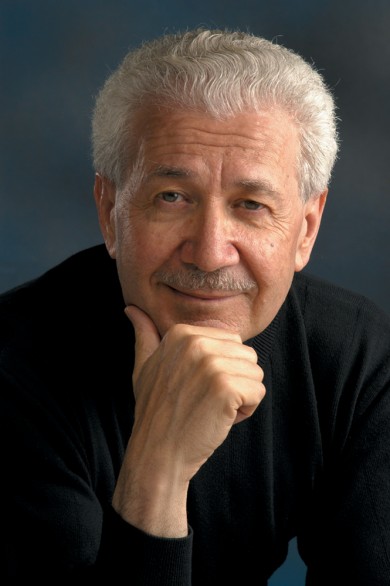

“I wanted to give the world another really romantic opera,” said DiChiera, a dapper man with silver hair, a neat moustache and the winning amiability of a man who has coaxed millions of dollars from the cultural gentry of Michigan.

“So much of my pleasure in opera has been coming to an opera and at the end of it feeling very moved, whether it’s Boheme or whatever,” DiChiera said.

“By the time you get to the final scene of Cyrano, a lot of people are in tears, and that really moved me. And I thought, ‘Okay, maybe I’ve succeeded in giving the opera world another romantic tear-jerker.’”

David DiChiera

Nothing could have been further from the minds of the composition professors with whom DiChiera studied at the University of California at Los Angeles in the early 1960s. In those days, serious contemporary music was in the grip of academic composers whose dissonant, atonal works turned off many listeners. And when DiChiera tried to develop his own style, he found that many of these professors — despite their revolutionary self-image — approached music with as conservative a mindset as that of any small-town kapellmeister.

“I always was a romantic in my whole soul and in what I loved about music,” he said. “But that was a period when most of the classical music composers were part of the university scene, and so there was a very rigid code about what was acceptable. If it wasn’t 12-tone, it was atonal, if it wasn’t that, it was electronic. The audience was never important in that approach. But the irony of it is, after 10 or 20 years of a certain style, it’s not new anymore.”

Frustrated that his musical vocabulary was being treated as a relic, he gave up his dream of becoming a composer and devoted himself to artistic administration. As founder and general director of the Michigan Opera Theatre, his current position, he amassed a record that was anything but conservative. While productions of La Boheme and La Traviata paid the bills, he worked hard to expand beyond the white, upper-middle-class audience that typically fills the seats in opera halls.

He commissioned a libretto by the African-American author Toni Morrison. He mounted a production of the Armenian opera Anoush, appealing to a significant Detroit ethnic group. And he gave pop opera idol Andrea Bocelli, whose career was built on Italian popular songs and famous arias with electronic amplification, a chance to make his North American opera stage debut — unplugged — in Massenet’s Werther. (By most accounts, Bocelli flopped, but the event sold a lot of tickets and attracted international attention.)

Meanwhile, a new generation of composers rebelled against the academic establishment, opening up the musical world to a wider range of styles, including the frustrated romanticism of David DiChiera. He composed a well-received set of songs championed by the soprano Helen Donath and began considering an opera. Bernard Uzan, who directs the FGO production, proposed a libretto based on the 1897 play Cyrano de Bergerac. The play tells the story of a French officer who believes he’ll never win the heart of the beautiful Roxane because of his large, deformed nose, and who writes beautiful letters to help another soldier win her love.

Finding the story the perfect vehicle for his musical style, DiChiera agreed. The work took seven years, and in a time-saving move, he hired the conductor Mark Flint, who will lead the FGO performance, to orchestrate it.

He found three companies to co-produce it, his own Michigan Opera Theatre, Opera Company of Philadelphia and Florida Grand Opera, whose general director Robert Heuer is an old friend and colleague from Detroit. When he played through it on the piano for Robert Driver, artistic director of the Philadelphia company, he recalls Driver’s stunned reaction.

“David,” he said, “why have you been wasting your life running opera companies?”

Yet DiChiera’s longtime administrative and artistic experience was not irrelevant to the task at hand. As he approached his first opera, he brought to the job the experience of a canny impresario who for 40 years had seen what brought audiences to their feet, what made them cry and what tended to empty the hall before the second intermission.

He composed the ending first. “I decided to write the final scene first because if an opera doesn’t end well — no matter how much has gone on before — it loses,” he said. “So I thought let me see if I can make this ending work.” He called up Leah Partridge, the soprano who would sing the role of Roxane at the Detroit world premiere and who will sing it with Florida Grand Opera.

“We spoke a lot about what high notes I liked and how I liked to get there,” she recalled in a telephone interview. The result, she said, was a part that played to her strengths and maximized the role’s vocal effectiveness. “I find his writing is very well suited to the voice,” she said. “The writing is very lyric and has lots of high, arching lines, which I love.”

Ruthlessly, DiChiera cut out ineffective sections. After hearing a performance in Philadelphia, he concluded the first act was dragging, so he trimmed it. He wrote a new aria for the tenor role of Christian, which will be heard for the first time in the FGO production. The result is an opera that tells a familiar story with lots of drama, big arias and a musical vocabulary that breathes contemporary life into 19th-century melodic and harmonic forms.

All of this is to the good, because contemporary operas present marketing and advertising problems that productions of Carmen do not. Although Florida Grand Opera has occasionally performed contemporary works, the enterprise is not for the fainthearted. “It definitely makes us nervous,” said general director Heuer.

He recalled a production of Stephen Paulus’ The Postman Always Rings Twice in 1988. “I still get complaints from people, saying don’t ever do that opera again, it was terrible,” he said.

With contemporary works, he said, it’s important to give audiences a few familiar things to which to cling. First there’s Leah Partridge, an FGO regular with proven audience appeal. The plot of Cyrano is well known. But beyond the familiar elements, there’s the power of the opera itself.

“It really contains everything that most people go to an opera production for,” Heuer said. “Absolutely gorgeous music for all the principals. The music written for Leah’s role is really spectacular. And because he was writing it for her, it really showcased her voice, with lots of spectacular coloratura. The final scene between Roxane and Cyrano is extremely moving. I watched in Detroit and audiences were in tears.”

Florida Grand Opera’s production of David DiChiera’s Cyrano runs April 23-May 7 at the Arsht Center in Miami. www.fgo.org; 800-741-1010.