Chicago Opera Theater’s fine cast, stylish staging make a worthy case for “Médée”

Micaela Oeste as Creuse and Colin Ainsworth as Jason in Chicago Opera Theater's "Médée." Photo: Liz Lauren

French Baroque opera is like a family member’s holiday dinner. You know you’re supposed to say you love it, but it always seems to need a little something extra to be successful.

So too, with Chicago Opera Theater’s production of Médée, which opened Saturday night at the Harris Theater. Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s 1693 tragedie-lyrique had its longueurs Saturday, largely due to inherent elements of the genre that have not dated well. But with a largely impressive cast and a skillful, stylish production COT made the best possible case for this fascinating if decidedly static work.

The middle installment of the company’s Medea trilogy, Charpentier’s opera is a tortuously faithful adaptation of Euripides’ drama via Pierre Corneille’s talky 1635 French adaptation. The scenario picks up the saga of Medea and Jason after they have fled Thessaly following the murder of King Pelias. Medea fears, correctly, that Jason is smitten with Creuse, the daughter of King Creon, even though she is betrothed to Oronte, prince of Argos.

Creon has his own political reasons for encouraging Jason’s affair with his daughter and tried to banish Medea from Corinth as a sorceress. After her confrontation with the unfaithful Jason, Medea calls on her dark powers for revenge on all, causing Creon to go insane (offstage) and, a la Handel’s Hercules, murdering Creuse with a fatal potion applied to a beautiful robe. (How many operas are there with death by poisoned clothing?) Creuse dies in great agony and, as the ultimate revenge on her husband, Medea murders their two children, abandoning Jason to his despair.

One can appreciate the historical significance of Médée, and the galant charm of Charpentier’s music as well as its forward-looking novelty, as in the storm sequence.

But for such starkly dramatic situations, Médée can be an awfully dull work. The acres and acres of conversational recitative, static action, and lack of variety in the vocal music make for long numbing stretches when you wish the French Revolution had come a century earlier.

The clear standout in the cast was Colin Ainsworth as Jason. The Canadian tenor possesses an ardent, youthful voice ideal for this repertoire, and he provided some of the finest singing of the evening. Dramatically, Ainsworth also plumbed a surprising emotional intensity in the weak, vacillating Jason, with his devastated agony in response to Medea’s horrific act lifting the opera out of its stilted conventions.

As Créuse, Micaela Oeste also made an impressive Chicago debut. The Arkansas native has a bright and flexible soprano and she sang with technical ease and vocal gleam. She also brought a charismatic presence and consistent engagement to Medea’s rival with the genuine pathos of her death scene offering the most compelling moment of the evening.

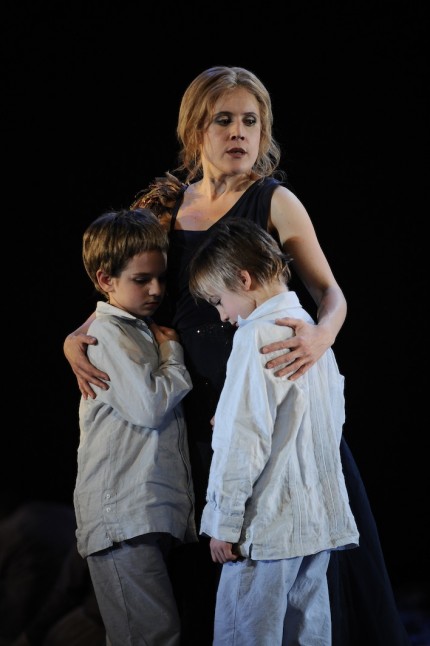

Medea (Anna Stephany) comforts her sons in COT's "Médée." Photo: Liz Lauren

In the title role Anna Stephany proved something of a disappointment. The English mezzo-soprano has a penetrating voice and certainly conveyed the imperious side of Medea, a woman who would even kill her children in revenge for her husband’s infidelity.

Yet ultimately Stephany’s Medea was a strangely generalized characterization, both vocally and dramatically. Her voice is imposing but decidedly monochromatic with a persistent wobble at lower dynamics. Even in Medea’s big moments, there was a lack of expressive specificity and nuance in the mezzo’s singing. Dramatically as well, Stephany failed to convey any of the emotional complexity or more vulnerable shadings of this chilling, fascinating creature.

Evan Boyer brought an apt authority and firmly focused bass to Creon. As Oronte, baritone Paul LaRosa didn’t seem warmed up at the start of the evening, but sang with more security and expression as the performance progressed. As the couple’s two confidantes Darik Knutsen was a worthy Arcas, Leila Bowie, a bright-toned fitfully unsteady Nerine.

Francois-Pierre Couture’s cost-effective unit set made a stylish, visually striking backdrop for the evening with its steel bars, three rolling glass cubes that served a variety of functions and several long, curved planks suggestive of a dismantled ship’s bow and nicely reflecting the exiled couple’s desperate travels.

James Darrah’s evening dresses for the women and suits for the men added a modern visual elegance to the Minimalist production, while his stage direction proved a more mixed bag. Darrah avoided the over-the-top excesses of last year’s COT production of Cavalli’s Giasone, yet some of his ideas just seemed baffling like the chorus members’ washing of their hands from large bowls (later artfully retooled for a clever depiction of Creuse’s death). Overall Darrah’s COT stage debut was auspicious, with the designer-director allowing the spare, primary human emotions to register without filling the stage with hard-sell postmodern distractions.

The COT ensemble assumed their various functions of Corinthians, Argians, love’s captives, demons, and phantoms with admirable energy, singing with vitality and corporate polish.

The allegorical Prologue with its obligatory but gag-inducing paean to Louis XIV was mercifully dispensed with, but with a single intermission, Médée still runs nearly three hours. One suspects there were more nuances and varied hues in the orchestral writing than sometimes emerged from the playing of an augmented Baroque Band on the raised pit. Some fitful lack of synchronicity between singers and orchestra apart, conductor Christian Curnyn led a vital, rhythmically pointed and elegant account of Charpentier’s score.

Chicago Opera Theater’s production of Charpentier’s Médée will be repeated April 27, 29 and May 1. chicagooperatheater.org 312-704-8414.