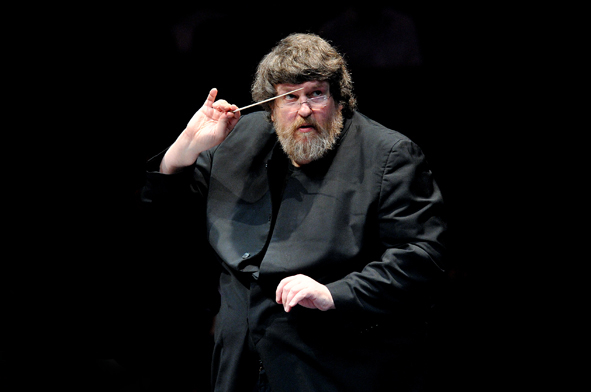

Colin Matthews’ Violin Concerto receives fiery U.S. premiere led by a loquacious Oliver Knussen

Oliver Knussen led the New World Symphony Saturday night in a program that included the U.S. premiere of Colin Matthews' Violin Concerto.

The English composer and conductor Oliver Knussen served as the genial, garrulous guide Saturday as the New World Symphony performed a bracing set of unfamiliar works from the 20th and 21st centuries.

Knussen, leading the orchestra at the Lincoln Theatre in Miami Beach, clearly loves talking about music as much as he does performing it, introducing works with a discussion of the influence of Scriabin or describing his discovery of one composer’s works at a London CD store.

This helped set the stage for compositions that few people in the audience were likely to know, but Knussen could go too far. When the composer Colin Matthews came on stage to introduce his Violin Concerto, he was left standing there, microphone in hand, as Knussen went on and on about the influences of Scriabin, Szymanowski and Stravinsky, until someone in the audience called out, “Can we hear it, please?”

The concerto, receiving its U.S. premiere Saturday, was performed with fire and incisive musical intelligence by the Canadian-born virtuoso Leila Josefowicz. In the program notes, Matthews says “There’s no unnecessary flashiness, here, and the concerto is not designed as a showpiece.” Whatever his intentions, several sections of the two-movement work seemed to be all flash, with Matthews allowing the violin to show off rapid-fire arpeggios, chords and passagework without any clear musical point.

Leila Josefowicz

In the first movement, the violin plays rhapsodic passages over a restless accompaniment in the orchestra. The violin’s tone becomes more aggressive, with spiky chords and figures establishing an opposition to the orchestra. The second movement was the more interesting of the two, with dark brooding tones on the lowest string of the violin over dirge-like notes in the orchestra. The speed and energy level increased, as the violin launched into blazingly fast passages that powered the piece to a sudden close.

Josefowicz combined a free, improvisatory style with an iron technical control. She appeared to toss her bow onto the strings without worrying about where it would end up, yet it seems to always land in the right place. Although the concerto was not the most gripping work on first hearing, it generally made clear where it was going with firm dramatic elements.

Knussen opened the concert with Scriabin Settings, his own orchestrations of five early 20th century piano miniatures by Scriabin. Despite Scriabin’s adventurous harmonies, this was easily the most accessible work of the evening. In the first, called Desire, Knussen created a mood of deep yearning from Scriabin’s piano piece, with otherworldly harmonies that seemed never to quite resolve.

The young American composer Sean Shepherd’s Wanderlust consists of three sections intended to evoke the Nevada desert, coastal England and Bilbao, Spain. Harmonically it is often harsh and dissonant, with tortured tones in the brass. But Shepherd’s music shows real compositional skill with orchestral tone colors, creating evocative, if episodic portraits of these landscapes.

A novelty on a program that was all novelties was the dramatic and powerful Symphony No. 10 by the Russian composer Nikolai Miaskovsky, who lived from 1881 to 1950, composing 27 symphonies in the shadows of better-known contemporaries Prokofiev and Shostakovich.

A dark and compact work, the one-movement symphony was inspired by a Pushkin poem about a devastating flood in St. Petersburg. From its ominous opening in the lower strings, the works rolls forward with a relentless intensity, with only a brief, wistful interlude in the winds offering some relief from the surrounding darkness. A fugal passage, growing increasingly frantic, evokes the oncoming disaster, and the work ends in a tone of tragedy.

Knussen raised his hands to quiet the applause, and the audience settled into their seats for an encore. It turned out there was no encore. There was just one more thing Knussen wanted to mention about Miaskovsky before sending everyone home.