Rufus Wainwright’s new song cycle undone by souped-up symphonic dressing

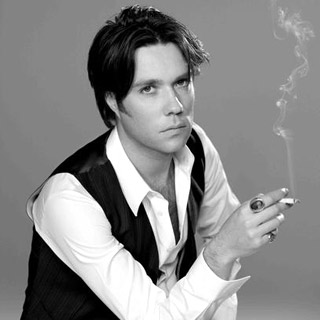

Rufus Wainwright

In this era of economic nonplenty, classical music organizations are knocking furniture over to attract young audiences, looking to shed their (supposedly) staid reputation and stuffy atmosphere to mine the popularity of crossover icons in the hope — usually fruitless — of luring their legions of admirers into the classical tent.

Rufus Wainwright is the latest pop icon to attempt to make the classical transition. The Canadian pop singer-songwriter’s opera, Prima Donna, was skewered by critics at its 2009 premiere in Manchester, though Wynne Delacoma was more positive in her TCR review of the North American premiere this past June.

This week saw Wainwright’s latest foray into the classical realm with the premiere of his song-cycle, Five Shakespeare Sonnets, with the composer as soloist with the San Francisco Symphony.

Wainwright, 37, is an undeniably gifted pop artist with an enthusiastic following as shown by the cheers and thunderous ovation that greeted his entrance Friday night in Davies Symphony Hall. His idiosyncratic vocals have an artless, quasi-Bocellian style of raw vulnerability, which, coupled with his boyish good looks and flamboyant personality, can make his admirers swoon.

Wainwright may call Five Shakespeare Sonnets — jointly commissioned by the San Francisco Symphony and the Ravinia Festival — a song cycle but despite the celebrated texts and the orchestral upholstery, it’s undeniably pop music, with Wainwright, amplified just as he would be at an arena event.

The cycle leads off with the weakest of the five songs, a plodding setting of Sonnet No. 43 (When most I wink, then do mine eyes best see), enhanced by a sweet-toned violin solo.

The ensuing Sonnet No. 20 (A woman’s face, with Nature’s own hand painted) is better. Introduced with a solo viola set against celesta, there is a surer fitting of the music to Shakespeare’s stanzas, allowing Wainwright’s soulful, plaintive style to be heard to better effect, as it segues without pause into the third setting (No. 10).

The Sonnet No. 129 (Th’ expense of spirit in a waste of shame) is along with the second song, the finest in the cycle with a worthy melody, even if the singer’s sudden falsetto leaps seem artificial and affected next to the eloquence of the text. The final setting of No. 87 (Farewell! Thou art too dear for my possessing) achieves the right sense of valedictory and coming full circle.

Five Shakespeare Sonnets show all the traits of solid pop music with accessible melodies and largely skillful word painting. The major issue is the orchestration. Unlike Prima Donna, where he had help, Wainwright claims credit for the scoring of this cycle and therein lies the problem.

The cycle is scored — overscored — for Mahlerian forces, which never cohere with the intimate simplicity of the vocal line. The souped-up orchestral writing feels forcibly grafted on, often inhabiting a parallel universe or loudly distracting one from Wainwright’s world-weary vocals.

With the massive discordant brass outbursts and chugging strings, the music is fatally inflated beyond what it can bear, the orchestra sounding foreign and loudly irrelevant to what is a pleasantly intimate but undeniably slender series of pop songs.

Presented on a smaller scale, Five Shakespeare Sonnets could yet have a future, and would likely be more convincing were it recast for chamber forces, string quartet, or even the composer alone at the piano. No complaints about the orchestra playing, with conductor Michael Francis drawing full-blooded if occasionally overbearing advocacy.

The flanking program was cleverly designed with works by two other genre-traversing upstarts who mixed the concert hall with more populist forms.

In Darius Milhaud’s La Creation du monde, Francis elicited alert, rhythmically incisive playing, yet while the jazz influences were firmly pointed, the performance was oddly straight-faced, lacking in satiric edge and humor.

Francis proved more convincing in Kurt Weill’s Symphony No. 2, heard in its premiere San Francisco Symphony performances. Cast in three movements, this rarely heard curio is light and spirited though there is also a restless agitation in the music that betrays some of its unsettled time, circa 1934 Berlin. The middle section is the most striking with a sting of Weimar acerbity amid the darker lyrical expression.

The symphony was Weill’s final orchestral work and while it’s clear he found a more grateful outlet for his talent in musical theater, it’s an intriguing listen if not an entirely convincing work. Francis drew dedicated playing from the San Francisco musicians, even with the whirlwind coda somewhat rushed off its feet.

The program will be repeated 8 p.m. Saturday. sfsymphony.org

Posted Nov 14, 2010 at 2:42 am by Ben

Wonderful to read your review!

However, I think it should be noted: as much as classical music organizations may hope to benefit from his name, these forays into classical composition, with opera in particular, have been Rufus’ long-stated ambitions. He’s still young, and he’s new to writing specifically in a classical vein. Hopefully with a little more experience and a little more temperance, he will indeed blossom in the classical world in his own right.