Opera Orchestra of New York is back with “Cav & Nav”

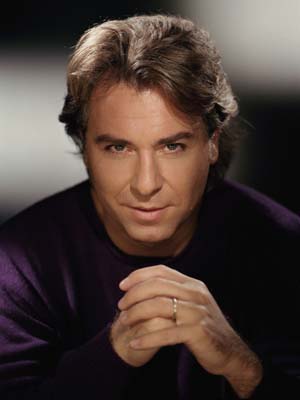

Roberto Alagna performed in "Cavalleria Rusticana" and "La Navarraise" Monday night with Opera Orchestra of New York.

The musical press turned out in force for the eagerly awaited return of the Opera Orchestra of New York Monday night after the financial meltdown forced the company to take a bye season last year.

But a definitive headline for the evening proved hard to determine despite the company’s characteristically strong cast and performances in a concert presentation of two one-act operas, Cavalleria rusticana and La Navarraise.

“Alagna Triumphs”? On any other night that might have worked; he looked and sounded in top form assaying both leading tenor roles (the only member of the all-star roster present in both halves of the bill). But he happened to be singing opposite two of the most compellingly accomplished women on today’s operatic stage — Maria Guleghina as Santuzza and Elina Garanca as Anita, the title role of Massenet’s fascinating La Navarraise — who had the edge for sheer vocal excitement.

Nor was the main story about the retirement of the indispensable Eve Queler, OONY’s founder, or about Alberto Veronesi’s unofficial coronation as the company’s new music director. These events mark a major transition in the New York opera scene. But for listeners who don’t know Maestro Veronesi from his continuing directorships in Palermo and Bologna, we will need to hear more than could be revealed in his brisk, pliant account of Mascagni and his confident reading of Massenet to know where his leadership might take OONY. As is usual with this orchestra, the evening included both impressive playing and some forgivable glitches, in this case mainly from the woodwinds.

In the decision to pair Cavalleria rusticana with La Navarraise, there was perhaps less boldness than meets the ear. OONY has a reputation for rescuing obscure and unjustly neglected works, but Cav is of course everywhere, while Nav is a former staple that is well recorded and was mounted by New York City Opera as recently as 2009. Erudite notes by Cori Ellison stressed verismo’s roots in French literature, and many commentators have joined her in calling Navarraise Massenet’s dramatically and musically sophisticated rejoinder to Mascagni, but this thesis is difficult to support in staged versions, let alone in concert.

Despite special effects including an offstage military band and plenty of gunpowder to simulate the atmosphere of the Carlist war in Spain, Massenet’s music does not attempt to suggest the passage of time as Mascagni’s does, even though it spans two days rather than Cav’s one. In concert it seems like an intensely melodramatic oratorio.

Production details, few as they were, also thwarted comparison of Mascagni’s and Massenet’s respective styles. For both operas, the orchestra and the New York Choral Society were massed on Carnegie Hall’s proscenium stage with the soloists in customary evening clothes. But in Cavalleria Rusticana, singers performed without scores (with the exception of Alagna, who dispensed with his for an all-out Mamma, addio). They moved about the stage, gestured in the manner of a semi-staged production, and made entrances and exits in accordance with the action.

In La Navarraise, all the soloists hewed to their scores and their chairs, singing passionately but without visually engaging each other to suggest what their stage actions might be — an especially weird spectacle in the ardent but disembodied love duet between Anita and Araquil, during which Garanca and Alagna did not even share a glance.

While the Massenet offered listeners musical freshness and perhaps even novelty, the Mascagni was more fully realized as a music drama in concert form. And in Maria Guleghina it had a Santuzza of greatness. While phenomenally gifted, Guleghina sometimes makes one aware of a distance between the technical excellence of her singing and the emotional core of her character. But not on this night. It is rare to hear any singer so superbly suited to any role as she is to Santuzza. Critics often praise the effortless power of her spinto instrument, but here her restraint and sincerity are even more impressive. Mignon Dunn treated her fans to an unusually sympathetic and warmly sung Mamma Lucia; as Alfio, Carlos Almaguer produced a rich, suave sound that was occasionally wayward when pushed beyond mezzoforte.

Alagna confirmed once again that he is the real deal, producing a luxuriously ringing, pliant sound that outlasted the evening’s vocal demands. One occasionally had the sense that he pushed or barked in the heat of a passionate moment, but this hardly detracted and certainly wasn’t necessary; the voice had more than enough size and metal to carry both dramas.

But the overriding excitement that propelled La Navarraise came from the star-caliber performance of Elina Garanca and from the superlative Russian bass Ildar Abdrazakov in the smaller role of Garrido. Garanca’s coloratura successes and even her Carmen do not hint at the power she demonstrated as Anita, whose lines soar as well as melt. Her beauty of tone was luxurious and lent credence to the improbable naivete of her character. Oddly disappointing, however, was her seeming withdrawal from the truncated mad scene that ends La Navarraise. The notes were all there, but the libretto and performance tradition call for demented, shrieking laughter from Anita, who abruptly slides into violent delusion. Without it, the opera’s resolution was unclear and anticlimactic.

Michael Clive is a cultural reporter and critic living in Connecticut. He writes for Opera magazine and blogs for Classical TV.com as The Operahound.