Botstein, SummerScape give eloquent advocacy to neglected Schreker opera

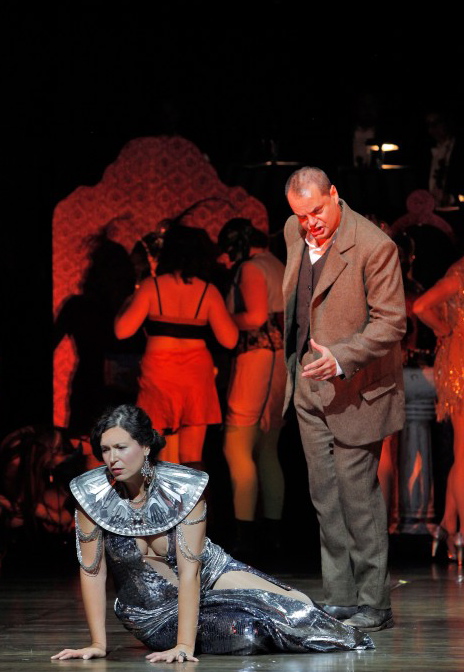

Yamina Maamar as Grete and Mathias Schulz as Fritz in Schreker's "Der ferne Klang" at the Bard SummerScape Festival. Photo: Corey Weaver.

When it comes to reviving rare operas worthy of a wider audience, few have a better record than Leon Botstein and the Bard SummerScape Festival. In recent years the Frank Gehry-designed Richard B. Fisher Center on the campus of Bard College has played host to Shostakovich’s The Nose, Szymanowski’s King Roger and Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots, to name but a few. Of these, The Nose, went on to the Metropolitan Opera in a production that ranks as a high point of Peter Gelb’s regime.

The other two operas are no less worthy of full Met treatment, and so is Franz Schreker’s Der ferne Klang, which is currently enjoying a Bard staging in a provocative production by Thaddeus Strassberger. Bard’s Ferne Klang follows hard on the heels of the Los Angeles Opera’s April production of Die Gezeichneten, which marked the first full staging of a Schreker opera in the American Hemisphere. Botstein previously conducted Der ferne Klang in a New York concert performance.

For those needing an introduction, Schreker—whose fortunes have been on the rise in Europe for some time—is one of several once popular Austro-German composers who (a) enjoyed flourishing careers before the Nazis came to power, (b) did not embrace atonality or serialism (a style the Nazis hated), and (c) were banned by the Nazis anyway, in part because they had Jewish blood. Schreker died in 1934. After the war nobody cared about these composers because serialism had become the rage.

Schreker has an image as one who took late Romanticism to its limits and beyond, both in his opaque, fanciful operatic subjects (he wrote his own librettos) and in his ripely chromatic musical style. Experiencing Der ferne Klang puts this in perspective. The plot is imaginative and a bit dreamy—at one point there is a reference to a dream within a dream—but it is cogent theatrically. And the music, while opulent, is also the product of a man who understood the theater.

Like other Schreker operas, Der ferne Klang deals with the struggle of an artist, here the young composer Fritz, who leaves his beloved Grete to cultivate a musical sound that has obsessed him, promising to return after achieving fame and fortune. But when he re-encounters her several years later, she is a ravishing Venetian courtesan. He rejects her but, tormented by guilt, comes to realize he still loves her. Reduced to working the streets, Grete nevertheless attends the premiere of Fritz’s opera, and the two are reconciled. But, as always seems to be the case in such situations, it is too late. Fritz is mortally ill and dies in her arms.

Composers like Schreker who never took the atonal plunge are routinely branded as conservatives. Yet in its way his music has a modernistic sound of its own. His harmonies often have pungent dissonances, and you hear suggestions of music outside the German tradition, such as Impressionism. Schreker is a master orchestral colorist and, like Strauss (though never really sounding much like Strauss), seems to revel in sheer musical complexity. The Venetian Act has moments when several musical events go on at once, with onstage musicians grouped together in a kind of surreal take on the Act 1 finale of Don Giovanni.

Strassberger seems to take a different tack for each of the three acts. Act 1 begins rather prosaically with a Fritz supposedly hauling a train of furniture—bed, armoire, dining table complete with place settings—as if to dramatize his downtrodden state (sets by Narelle Sissions, lighting by Aaron Black). But after Fritz departs, the unhappy Grete interestingly sings her big monologue in a movie theater while watching a silent film about a girl whose plight is similar to her own.

The central Venetian Act is a highly lavish affair with glittery mirrors and doors for individual courtesans. It is here that Mattie Ullrich’s costumes are at their most outlandish. Strassberger cleverly sets Act 3 at the site of the cast dinner following the performance of Fritz’s opera; the opera is still in progress when the act opens. But his ingenuity gets the better of him in the final scene. Der ferne Klang seems to tell us that art and love cannot be compartmentalized, as Fritz tried to make them initially, but rather must nurture each other, a point made symbolically by the reconciliation of the lovers in the context of Fritz’s new opera. But Grete appears in what we later recognize to be simply a vision, never making physical contact with Fritz; the ‘real’ Grete desperately arrives only after Fritz has expired, as if they never reconnected. The emotional impact that Schreker surely expected the reconciliation to make was lost.

Mathias Schulz meets the punishing heldentenor demands of Fritz’s music most ably, even if the voice sometimes sounded a little tight; more important, Schulz compellingly suggests Fritz’s growing maturity. As Grete, Yamina Maamar soars vocally over the orchestra and tellingly conveys the girl’s plight, though there are moments of unsteadiness in mid-range.

Others in the cast include Jeff Mattsey, an engaging figure as a Hack Actor; Susan Marie Pierson in several roles, including the Old Woman who sets Grete on her course towards Venice; Corey McKern as the Count who wins Grete and then abandons her; and Mark Embree as the sympathetic lawyer, Dr. Vigelius. The last participates in an arresting dialogue with Fritz, urgently telling Fritz that he has brought Grete with him, while Fritz for a time remains oblivious, wrapped up as he is in the “distant sound” (arpeggiated chords played by harp, celesta and piano).

Botstein, leading the American Symphony Orchestra, has the music well under control and his sense of pacing ensures that there are no longueurs. There is room for a fuller appreciation of Schreker’s variegated orchestration, and sometimes greater rhythmic intensity would have been welcome. But Botstein’s skills as an advocate are potently enlisted. This is music that one wants to hear again.

Der ferne Klang runs throught August 6. www.fishercenter.bard.edu