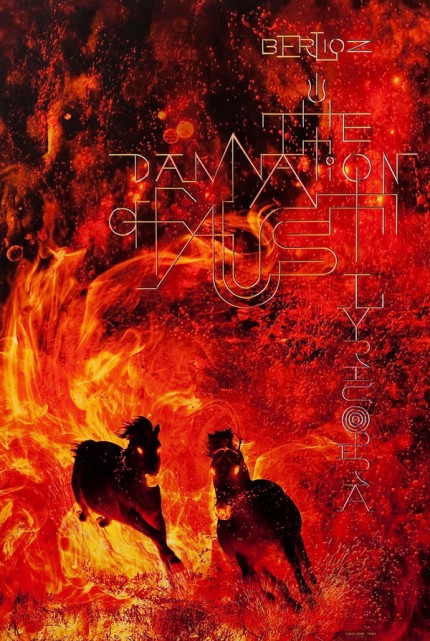

Berlioz makes a belated Lyric Opera debut with “Damnation of Faust”

The Lyric Opera of Chicago’s storied history is made all the more fascinating by the fact that it has never presented any work by Hector Berlioz.

The company will break that moratorium Saturday night when The Damnation of Faust begins its month-long run with Susan Graham as Marguerite, Paul Groves in the title role and John Relyea as Mephistopheles. Sir Andrew Davis will conduct.

Compared with other Berlioz operas, La Damnation de Faust is a highly unorthodox dramatic work that few would call proper theater. Scholar Fred Plotkin argues that Berlioz only produced three genuine operas in his lifetime: Benvenuto Cellini, Les Troyens and Beatrice et Benedict. Even Berlioz himself wanted the 1846 work to be performed oratorio-style, citing that all the theatrical trappings of traditional opera would stifle the imaginations of his audience. Instead, Berlioz conceived Faust as an “opera de concert.” And for most of its history, its natural home has been on the symphonic stage.

Presenting it in the opera house, as British director Stephen Langridge will do in this brand new production, is a uniquely compelling task. Even the Metropolitan Opera went 102 years without staging it, only recently doing so in a new production by Robert Lepage in 2008.

Hector Berlioz

“It’s such demanding fun for an impossible piece,” Langridge says. “It was written for a theater that didn’t exist. Berlioz couldn’t manage to stage it and while he tried, it didn’t work to his satisfaction. It really is an impractical work.”

In twenty rip-roaring tableaux, there are rapid scene shifts from heaven to hell, tavern to bedroom, etc. Often called a “chorus opera,” the 80 choristers are essential to an effective staging, changing at once from townspeople, sylphs, fiends, soldiers and so on. They provide the context of Faust’s personal narrative.

Depicting each tactile change would be counterproductive, Langridge believes, and he will not be adding naturalistic sets to illustrate each scene. “People think it’s not stage-able but it is because of the technology of theater, and also because of the development of our popular imagination. You don’t have to see every naturalistic swirl. This is where it requires imagination,” says Langridge, adding that Berlioz didn’t want to tame his ideas within a rigid framework.

In the final pandemonium scene, for instance, Langridge takes Faust’s descent into the abyss and visualizes it with lively dance movement and staging, giving it an “end of my life, flash before my eyes” quality. He accomplishes this by drawing on imagery from earlier in the piece.

Given that current technologies weren’t available 150 years ago, Berlioz’s Faust myth now thrives on our modern advancements. Projections designer John Boesche, whose handiwork in the Lyric’s stunning 2008 Lulu won’t soon be forgotten, is playing a crucial role in that department.

“The general intent of the projections is to make visible the inner workings of Faust’s mind. We see this build in the first scene where we first meet Faust in his study,” he says. “But the strongest visualization of Faust’s inner torment is seen in Scene 11, the Evocation.”

Boesche tells us that director Stephen Langridge has been disciplined about revisiting this production with a very modern aesthetic. “Sets, costumes, lighting and movement are all in a very contemporary vision. The projections are approached much in the same way,” says Boesche.

"Bed of Roses" by Gregory Crewdson.

Specifically the production drew visual inspiration from two interesting sources. During a rehearsal last week, France-based Greek designer George Souglides said that he and Langridge saw a kindred spirit in the photography of Gregory Crewdson, where noirish scenes of Americana are arranged like dreamy, cinematic stills.

They also saw Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s 2006 film Des Leben der Anderen (The Lives of Others) and fell in love with the beautiful cinematography and its vivid portrayal of a Soviet-bloc dystopia. The movie chronicles the close monitoring of state officials who spy on potentially subversive citizens. Like Mephistopheles hovering over Faust, the comparisons inspired them.

For Faust they similarly invented an Eastern bloc atmosphere, which is supposed to be set in Leipzig. The soldiers’ uniforms are from Hungary and they invented a flag based, more or less, on East Germany’s. “It’s a slightly mythologized recent past, but not a naturalistic piece,” says Langridge, who will be making his Lyric debut. “We didn’t want it to be sensitive to Chicago in 2010. Not that it couldn’t work, but we felt it needed a little distance with so much military stuff going on.”

After a dreadful staging of Damnation in November of 1846, Berlioz wrote in his Memoirs that the work was twice performed to a “half-empty room” in Paris. Berlioz couldn’t understand why a music-obsessed public cared so little about his new piece as if he were only an “obscure student at the Conservatoire.”

The results should be markedly different today where locals have been starved for theatrical Berlioz. Surely the Lyric Opera’s scrapped 2003 production of Benvenuto Cellini still lingers in the mind.

“I’m sure it will be the first of many Berlioz operas here in Chicago,” Langridge says in earnest, but with a hint of playfulness in his voice. “And the audience will be clamoring for more on the 20th of February!”

Berlioz’s The Damnation of Faust opens 7:30 p.m. Saturday at the Civic Opera House and runs through March 17. www.lyricopera.org; 312-332-2244.