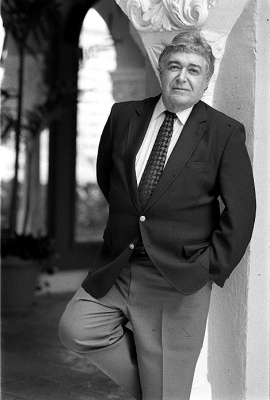

Requiem for a great friend who also happened to be a great composer

When I moved from Chicago to take up a new job as music critic of the South Florida Sun-Sentinel in August of 2000, the second voicemail awaiting me in the Fort Lauderdale newsroom was from Marvin David Levy. (The first was from an elderly woman asking if I could recommend a piano tuner.)

“Hey, this is Marvin Levy,” said a raspy voice in an ironic, vaguely conspiratorial tone. “You reviewed an opera of mine in Chicago. Give me a call sometime.”

That began one of the great friendships of my life, which ended last month when Marvin died at age 82 in a Wilton Manors nursing home after a short illness.

I had reviewed Marvin’s opera, Mourning Becomes Electra, for The New Criterion in 1998 when the Lyric Opera of Chicago premiered the revised version. I was knocked sideways by the performance and the work, which, in its roiling energy, dramatic intensity and whipcrack scoring still remains unique and, in many ways, unequaled in American opera.

During the nine years that I lived in Florida and worked as a newspaper music critic, first at the Sun-Sentinel and later at the Miami Herald, Marvin and I would get together for dinner every three or four months–usually at his favored Fort Lauderdale emporium, Casa D’Angelo–and speak on the phone more frequently.

My conversations with Marvin were a relief valve for him—about his inability to finish works, frustration at the lack of productions for Mourning and assorted money worries. He also listened to my concerns—hassles with editors, turbulent romantic relationships and the inexorable implosion of newspaper journalism in South Florida that was also taking place around the country.

But most of all we talked about music.

He seemed to know everyone from those high decades of opera singing in the 1950s and 1960s–singers, composers, directors and impresarios. Marvin was one of the most honest people I’ve ever met, and with the greatest sense of humor. He had an endless supply of tales, which were sometimes poignant, often withering and always hilarious.

For all his scathing honesty and sarcastic humor–which, unsurprisingly, didn’t endear him to everyone–Marvin had an unjaded, almost childlike fascination for opera and, especially, the soprano voice. He turned me on to the celebrated 1974 live video of Montserrat Caballe in Bellini’s Norma. “Watch it,” he urged. “It will change your life.”

Marvin was always a pure-hearted enthusiast about music and his art. He never ceased talking about revered performances he attended, usually one he found memorable for a favorite soprano. “God, I’ll never forget that night,” he would often say.

Most of his favorite singers were in the past, something I occasionally jibed him about. When I praised a young soprano in a Miami production of Handel’s Giulio Cesare, he scoffed. “Do you know who my first Cleopatra was?” he asked. “Cleopatra?” I responded. He laughed heartily.

Yet for all his cynicism and sardonic crankiness, Marvin was a vulnerable figure and often taken advantage of by those he trusted.

In the 1980s Marvin was nearly as well known for his two-year stretch in federal prison for conspiracy, as a bagman for a million-dollar pot smuggling ring. I finally worked up the nerve to bring it up after I had known him a couple years and he discussed it with characteristic candor. “I did it,” he said ruefully. “I was stupid.”

He would keep me posted about developments with his music and I followed all new productions of Mourning. When Seattle Opera produced Mourning in 2003, I flew out there and reviewed it for the Sun-Sentinel. (This was a more generous era for newspaper travel expenses, especially at the Sun-Sentinel under my enlightened features editor, John Dolen. When I later moved to the Miami Herald, I couldn’t get money to go to Hialeah.)

Marvin had extremely high standards for singers, especially in his own works. I still prize a hilarious, rambling, late-night voicemail he left about a singer in a B cast of Mourning he felt inadequate. (“She can’t sing the role. She cannot sing the role!!”)

He was famous for getting thrown out of rehearsals, which happened with the Mourning productions in Chicago and Seattle. He’d later admit it was well deserved. “They were right to do it,” he’d say. “I was a pain in the ass.”

We sparred, politely, over his habit of constantly revising earlier works, especially Mourning. I felt his extended ending with the Mannon ghosts returning made the opera too long and was less effective than the “Chicago version.” Marvin was adamant that the longer version was better. “Maybe I’ll rewrite it again,” he’d say in that singsong lilt with a laugh.

He worked fitfully on other works, which I always encouraged. An opera on Jean Genet’s The Balcony occupied him for some time. He was greatly moved by the HBO film of Tony Kushner’s Angels in America and was fired with enthusiasm for that project as well.

Marvin talked wistfully from time to time about moving out of Fort Lauderdale and back to New York, hoping that would reignite his creative spark. “I’m dying here,” he said often.

But I think deep down he knew that Mourning was his masterpiece, and, like Pietro Mascagni, he had scored his greatest operatic success at a young age and was destined to never repeat it.

I saw Mourning three times, in Chicago, Seattle and Miami. I sometimes worried that the opera wouldn’t live up to my memory of the last performance and maybe my friendship with the composer was causing me to subconsciously overstate the merits of the piece.

Not the case. If anything, I was more blown away by Marvin’s score with each performance—the originality, the audacity and panache of the writing for orchestra and the touching humanity underneath the bleak, torrid scenario of the cursed Mannons.

I am grateful to Susan Danis for following up my suggestion to present Mourning at Florida Grand Opera. That 2013 FGO production received great reviews but, most importantly, it gave Marvin one more chance to see his opera performed in his hometown—as well as enjoy the media attention he guiltily confessed that he enjoyed.

I saw Marvin less frequently after I moved back to Chicago in 2009 to start up Chicago Classical Review, but we would still talk on the phone and get together for dinner whenever I returned to visit. Dinners required more logistical planning as Marvin’s mobility declined—first, he using a wheeled walker and later was confined to a wheelchair. Marvin was still always nattily dressed in a suit and tie. Sometimes he would zone out at dinner and become non-communicative while other times he was as witty and nearly as quick as his old self.

When I visited Marvin at the end of January in a nursing home, the change was drastic from just a few months earlier. I barely recognized the shrunken cadaverous figure from the smiling mischievous cherub I knew. He was sleeping when I was there but a nurse gently woke him. “Larry!” he said weakly, his face lighting up with a smile. “What are you doing here?”

We talked for a few minutes until he sunk back into the sleep which was now his normal state. I visited again a week later, and he had declined significantly. He was unconscious yet being fed by a nurse and ate greedily yet never opened his eyes and couldn’t communicate or speak. Two days later he was dead.

On that last visit I promised him to do all I could to try to secure a first commercial CD release for Mourning under the aegis of my American Music Project. I thought I saw a faint smile on his face.

Thanks Marvin for much laughter, great dinners, amazing stories and conversations, but, perhaps most of all, thanks for Mourning Becomes Electra.

Goodbye, my friend.