Muti talks Verdi: Conductor to lead off his fourth CSO season with a very Verdi month

Riccardo Muti opens the Chicago Symphony Orchestra season this week with music of Verdi and Brahms. Photo: Todd Rosenberg

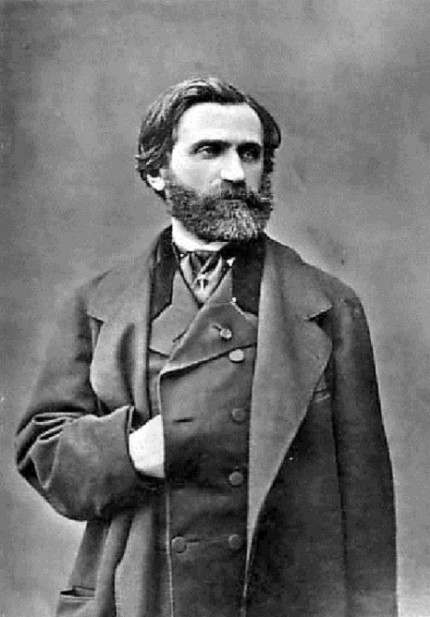

One can never accuse Riccardo Muti of false enthusiasm, not least when discussing the music of Giuseppe Verdi.

Widely acknowledged as the foremost living interpreter of Verdi’s music, Muti is launching his fourth season as Chicago Symphony Orchestra music director with a veritable Verdi feast.

Tonight Muti will open the CSO season with a concert at Morton East High School in Cicero performing excerpts from Nabucco and La forza del destino alongside Brahms’ Symphony No. 2. The Brahms will be repeated Thursday at Symphony Center, along with Verdi’s ballet music from Macbeth, and overtures by Verdi and Johann Strauss, Jr. The CSO gala ball on Saturday will offer another all-Verdi mix adding music of Ernani and the Overture to I vespri siciliani.

The biggest Verdi events will follow. Muti leads soloists, the CSO and CSO Chorus in concert performances of Macbeth, one of Verdi’s first great successes, September 28 through October 6. And on October 10, Verdi’s 200th birthday anniversary, Muti and the CSO will reprise their Grammy-winning account of the Verdi Requiem with a performance that will be live-streamed on the internet.

Shortly before flying to Chicago to begin rehearsals, the CSO music director spoke from his home in Ravenna about Verdi, his approach to his music, and why Verdi operas prove just as suitable for the concert hall as the opera house.

LAJ: While Verdi’s operas are widely performed and known to even casual opera-goers, what is it about his music that first made such a strong impact on audiences and continues to set him apart from all other opera composers even today?

RM: Verdi really was a musician of the future. Verdi came out of the Neapolitan school. His first teacher was Lavigna, from the south of Italy, from Altamura. He was a great teacher and Verdi respected him throughout his entire life.

When he was younger Verdi was in Parma—Italy was not united yet—and so he was close to the border of the Austro-Hungarian empire and [was exposed to] music of Mozart, Haydn, Schubert and Beethoven.

The study of Verdi is really [the history of] the European view of music. So, having knowledge of the Austro-German music and knowledge of the Italian and especially Neapolitan music. Even those first Verdi scores are so well written. Mahler considered the orchestration of the Verdi operas absolutely perfect.

The fault of many conductors [historically] has been to please the singers and to reduce the orchestra in the pit. Many didn’t care so much to understand and perform the music of Verdi. Verdi was never a composer for show or beautiful voices or to be used for vain purposes.

In Italy Toscanini really was the greatest warrior in defense of Verdi. When he left to go to America, the attitudes toward Verdi became very sloppy, and we Italians then brought these bad habits all around the world. As Furtwangler said, “Tradition is the memory of the last bad performance.”

So little by little, over time conductors started to make all the accompaniments of Verdi very aggressive and very brutal. Very vulgar. When I did Macbeth with the Vienna Philharmonic, I said, “Look, when you play Schubert with the same accompaniment, you play with great aristocracy and nobility. But when you see Verdi’s name written on the score you play oom-pah-pah, oom pah-pah! It makes an offense to our culture.”

Of course, Verdi didn’t even call [the orchestra writing] accompaniment but “embellishment.” Because even one chord must be played in a certain way. It doesn’t mean that every forte chord must be played in the same way. Because every chord is the conclusion or the preparation of a dramatic phrase. So it requires a phrasing and intensity that are extremely different one from the other.

But to do that, you must first know this music and how to perform it. You must be able to tell the musicians what to do and why and you must tell the singers what to do and why. It means, first, the conductor must know what he is doing.

Secondly, he needs time. That is the reason why I hate singers that arrive at the last moment. (But never with me because I would never accept them!) They arrive one week or three days before a performance. That’s not a performance, that’s—-you can use the worst American word.

When I did Otello with Placido Domingo, he had already done more than three hundred performances as Otello. But because we know each other and he knows my work, he came to La Scala in 2001 and he stayed with me for one month of rehearsals. One month!—not performances, just rehearsals. Because he was interested in a new approach with a conductor new to him for this opera.

When we did Otello in Chicago, [Aleksandrs]Antonenko, the tenor, worked two years with me, coming every three months to my house in Ravenna, and learning the role little by little.

This is the way opera was prepared many decades ago and this system has been completely forgotten. It would be a tragedy of the operatic theater if this no longer continued. It would be a disaster. Because there would not be any more time to get the singers to work together as a team with the same ideas and the same concept about the interpretation of the opera.

LAJ: What is it about presenting operas in concert form that appeals to you more these days than staged performances?

RM: The Nabucco that I just did in Salzburg with the orchestra and chorus of the Rome Opera was also in concert form. Because after forty-three years of summer festivals, I said I wanted to enjoy some free days in July and in August. So that is the reason why I said I don’t want to stand all the time for the rehearsals that are necessary to do an opera on stage.

Because if you are a serious conductor, to do an opera on stage, you need one month of rehearsals and two months to devote to the performances. I have done so many operas in Salzburg—more than two hundred performances—so I said if you need a Verdi opera from me, I prefer to do it in concert form. Because it takes much less time and the orchestra was already prepared since we performed the opera a few months ago.

So all this introduction is to say that I like being able to do operas in concert form because the public has the possibility to [experience] the music without any, I would say, disturbance of sometimes very strange Regie.

As you know very well, today stage directors have very strange ideas about operas. Many times they create another story on top of the music that the music tells.

I have great respect for directors like [Giorgio] Strehler or Peter Stein. They read music, they know music, and they understand the music. Then they can create something that can help the music to become more alive and not do anything that is against the music.

LAJ: What is it about Macbeth that was responsible for making it one of Verdi’s first great successes?

RM: Macbeth is an opera of introspection. There is not so much action, and the killing is on the side and offstage. Most of the opera is about the psychology between Macbeth and Lady Macbeth. So, it’s an opera that can be done in concert form without any problems. Actually you have more of a possibility to go more deeply into the story and into the characters.

In the same way Nabucco is an opera of piety. It’s an opera of situations that are more psychological than action. Also Nabucco [in his recent Salzburg performances] was accepted extremely well because people can hear the opera where the action is practically nonexistent and they can concentrate on the music.

Verdi wrote the first Macbeth for the Teatro della Pergola [in Florence]. Than many years later he practically revised much of the opera.

LAJ: Which version do you prefer?

RM: I always do the revised version of Macbeth. There is a big, big difference. In the second version, there is the famous aria, “La luce langue” that was added and some other arias.

Some arias that were written for the first version were technically very difficult and not so interesting musically, so Verdi cut these arias and wrote new ones. In the first version, he had written the Sonnambula scene, which is one of the great masterpieces in the opera, so it stayed in the second version.

Also in the first version we have the final aria for Macbeth, a short aria but very deep, in which he throws away the crown, the symbol of the power and all the choices he made that he is responsible for. But in the second version, Verdi put away this aria. I don’t know why. The second version is more impressive for the public because it ends with a big chorus.

Sometimes when I do Macbeth I restore the aria. There is much more humanity in the aria and, in a way, we are moved by the words that Macbeth says.

The aria is fine but then the [original] finale is weak. So Verdi was right, in the end, to change the finale and to take away the aria. So, like Lady Macbeth, Macbeth disappears at the end offstage and they end up in the darkness and we don’t know any more about them.

And so the second Macbeth score is much more refined. Verdi was more mature when he revised the opera. The first version is more fundamental and simple while the revised version is much more sophisticated. Today the first version is performed only for scholarly interest.The second is the great opera we know.

LAJ: Some productions combine different elements from both Macbeth versions.

RM: Generally, I am against putting together a poupurri of the different versions like a mixed salad.

Like in Don Carlos, Verdi spent a lot of time thinking about which version was the right one. He wrote first the five-act version for Paris. Then the five act in Italian for Italy. Then he went to the four acts in Italian and then he went back to four acts in French. Sometimes conductors and directors like to put together several versions but then you are performing a monster.

LAJ: Verdi also added the ballet music for the second Macbeth for the Paris performances, which many productions don’t use since they feel it’s alien to the story.

RM: This is something the stage directors say because they don’t know what to do. But if you have a very intelligent director he knows what to do with the ballet. Especially today when you can use the ballet and the symphonic music with choreography with the ambiance and the atmosphere of the story itself.

I did Moïse et Pharaon of Rossini in Salzburg and Roma. The ballet is fantastic music but in Salzburg the director tried to do something very original and it didn’t fit with the rest of the performance. In Roma, it had the same atmosphere and character as the opera itself and so the public doesn’t find itself lost in the ballet.

Along with I vespri siciliani, the ballet music in Macbeth is the best symphonic music Verdi has ever written. Verdi wrote music that was very deep and very interesting.

It’s very, very difficult music. At that time the Paris opera orchestra was the best orchestra in the world, and so Verdi wrote music that was extremely virtuoso, technically speaking, and very demanding. It’s not Giselle, you know?

LAJ: With all the familiarity of Verdi’s operas it seems that their very popularity often makes people overlook the more subtle aspects of his art like how the orchestration and scoring reflect the dramatic situation on stage.

RM: You can speak for one hour of how fantastic is the Preludio in Traviata. For instance the beginning (sings), then the violins play (sings)—the combination of the wind instruments, the use of the strings in the upper register. Its a score that is extremely sophisticated. But you need a conductor to prepare ahead of time to understand the piece. Not just the [balancing] but you have to know why he used certain timbres.

For instance in Macbeth, you have (singing) dee, dee dee deedee dee. That is like the sound of a bagpipe and it connects the atmosphere with old Scotland. The motifs are like symbols and anytime Verdi wrote about destiny or fate he used a theme that is very circular (singing the main theme of Forza del destino) or (singing a theme from Macbeth) or in Rigoletto (sings the fate theme). It always comes back and closes on itself.

So, to understand these things you need a lot of time. You need a lifetime.

I believe that Verdi was an aristocratic composer, from the beginning with the very first opera to the last one. Every opera is a voyage and generally every opera is an improvement on the one that came before.

Verdi said that all the operas, through Otello, he wrote for the public. Only Falstaff he wrote for himself. And Falstaff is the greatest opera he wrote. It’s less popular, of course, than Traviata, Rigoletto or Trovatore.

But Falstaff is a compendium of all the operas that had been written before. It’s a sort of cathedral—with irony, with nostalgia, with tears but also with a smile about an entire life.

In every opera, Verdi is every character. Verdi is Rigoletto, Verdi is Riccardo in Ballo un Maschera, Verdi is Don Carlo, and Verdi is Falstaff.

And, always, Verdi’s music is a reflection of a very noble soul.

Riccardo Muti opens the Chicago Symphony Orchestra season 7 p.m. tonight at Morton East High School in Cicero. The program will include Brahms’ Symphony No. 2, the Overture to Verdi’s Nabucco and arias and choruses from Nabucco and La forza del destino with Barbara Frittoli, Luca Dall’Amico and the CSO Chorus. cso.org; 312-294-3000.