After a 21-year absence, Mutter returns to perform with Muti, Chicago Symphony at Orchestra Hall

Anne-Sophie Mutter returns to the CSO after a long absence Saturday night.

Anne-Sophie Mutter carries with her such international renown and, through her glamorous press photos, a persona of such cool reserved beauty that one anticipates an interview with the celebrated German violinist might be an arduous experience for both sides.

In fact, the reality is quite the opposite, and Mutter proves as open, engaging, and unpretentious as she is richly talented.

“I’m so sorry!” she exclaims, speaking on the phone from Baden-Baden where she was appearing with Valery Gergiev and the Mariinsky Orchestra. “My rehearsal went forty-five minutes long and it totally screwed up my afternoon!”

Anne-Sophie Mutter will return to Chicago for a single performance of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto with Riccardo Muti and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Saturday night, an event marking the CSO Women’s Board’s inaugural Symphony Ball (formerly the Opening-Night Gala).

While Mutter, 47, has regularly visited Chicago over the years as a recitalist, Saturday’s event will be her first CSO collaboration since 1992 at Ravinia, when she performed and recorded the Berg concerto with James Levine.

Even more amazingly, it will mark Mutter’s first downtown appearance with the CSO in 21 years. (Sir Georg Solti conducted in 1989 and the repertoire was also the Beethoven concerto).

“Really? Are you kidding?!” she says sounding genuinely surprised. So, why the long absence? “I have no idea! I feel insulted almost!” she says with a laugh.

“But listen I’m thrilled to come back with Maestro Muti for the Beethoven concerto. This is going to be fabulous.”

Mutter made one of her early discs (of Mozart) with Muti in the early 1980s when he was the new young music director of London’s Philharmonia Orchestra. More recently, she performed with him in Milan before the conductor’s battles with and eventual divorce from La Scala.

“The way he has shaped the orchestra in Milan over the decades is incredible,” says Mutter. “It was just such tremendous music-making.” I was very sad to see that [partnership in Milan] not continue.”

For the violinist, it’s the unusual combination of Muti’s “fire and incredible seriousness” that makes their musical collaborations so memorable.

“Very often, you find a musician who is terribly serious but with a bad lack of fire,” says Mutter. “Or you meet someone who is a total firehead but he cannot control the music live.”

“[Muti] is one of the great maestros of that generation. With Maestro Muti’s strong concern for sound color and sound quality, I think the match with Chicago will really be a match made in heaven.”

Like many, Mutter was struck by Muti’s charm and sense of humor as well as a personal kindness, which contrasts with his fierce concentration on the podium.

“I remember when I played the Tchaikovsky concerto with him in Philadelphia and I was expecting my first child,” she recalls. “And he sat me down, closed the door and gave me a lecture about how important it is to slow down on concerts, stay home and take some time off.”

“It’s a great human quality to take a younger musician to the side and [advise them], caring about the non-stage things of life. I very highly think of him as a human being as well as a wonderful musician.”

With her good working relationship with Muti, I said it will likely not be another two decades before she returns to Chicago. “Yes. At my age, we cannot take that risk!”

The Beethoven concerto has figured in Mutter’s career almost from the start, unusual in that many instrumentalists wait to approach the concerto the way most dramatic tenors wait till late middle age before they tackle Otello.

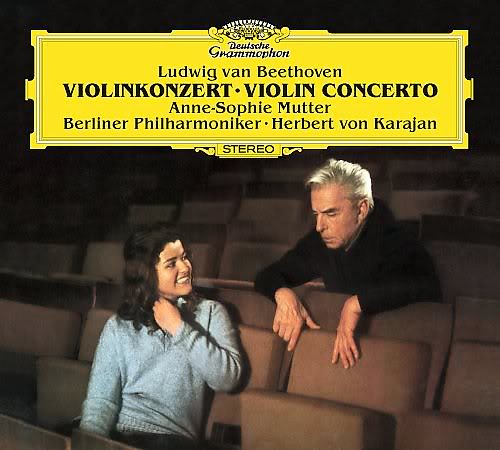

Follwing her debut Mozart disc, the Beethoven concerto was the second of her acclaimed recorded collaborations with her mentor, Herbert von Karajan, and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, recorded when Mutter was just 16. “I don’t know why but he decided it would be a good drill to get into the Beethoven,” she recalls.

After countless performances of this most interpretively tortuous of all the great violin concertos—and a second recording in 2002 with Kurt Masur and the New York Philharmonic—Mutter says that while her general approach to the music has not changed, she still finds this work an extraordinary challenge every time she revisits it.

“Beethoven is just such a titanic, larger than life figure,” she says. “The violin concerto really is every time like climbing Mount Everest, You never know if you’re going to make it to the top!”

“You have to have an incredible sense of timing and of phrasing. If you ever fall into the trap of trying to play one beautiful note to the next one, you will totally miss the spell of the language. The verb is at the end of the sentence and you really need to have this inner tension and this ‘directional’ playing, which is what Beethoven is all about.”

“The tempo, especially in the first movement, needs a timeless quality, it needs to be expansive. But there are so many subtle details. When it comes to accompanying and the orchestra has the leading voice, I think my playing chamber music and a lot of contemporary music has added a lot of colors and insight to the score.”

“But I have to tell you, I’ve been playing it for thirty years and it never comes easy,” she adds. “You can not ever ‘conquer’ Beethoven.”

Mutter has been nothing if not eclectic in her significant discography, recording all the cornerstones concertos, many more than once, but also including offbeat byways such as Lutoslawski and Wolfgang Rihm. Most striking is her juxtaposition of Bach concertos with the seismic upheaval of In Tempus Praesens, a concerto written for her by the Russian composer, Sofia Gubaidulina.” It’s such a gorgeous piece,” she says. “I hope I can bring it to Chicago one of these years.”

Mutter’s most recent recording is her new disc of Brahms violin sonatas with Lambert Orkis, her regular keyboard partner for more than two decades.

“I think the key is she has a natural inclination, a natural gift for the music she plays,” says Orkis. “I mean, a lot of thought goes into it, there’s her strong training, of course.

“But she really does care about the music,” says Orkis. “She cares deeply about the music, and she brings that dedication to every performance.”

Mutter prefers performing the three Brahms sonatas in a single evening, which she and Orkis did extensively before their recent recoding. “The G major has always been my favorite piece. All three sonatas were written in summer months on vacation by Brahms but they have such different styles that it’s fun to play in an evening together.”

“The A major is so open, fresh and welcoming. The G major is more introverted and the saddest piece of chamber music you can possibly imagine. And there’s the D minor, which was written for von Bulow, who was such a stormy eruptive man.”

While she never listens to her recordings once they’re finished, Mutter said she’s particularly proud of her new Brahms set, especially the G major sonata. “This was recorded in one take. It was raining and we felt things were going so well, we just continued without even pausing between the movements. We felt, ‘Gee, this is going to be quite good!'”

The German violinist has an intensive schedule of activities this season, notably a daunting series of events slated as artist-in-residence with the New York Philharmonic. These include Beethoven Trios with Lynn Harrell and Yuri Bashmet, Mozart’s complete violin concertos, the Beethoven concerto, a new work by Wolfgang Rihm and the world premiere of Time Machines, written for her by Sebastian Currier.

“Sometimes, I wake up in the morning and I think, ‘Oh my God!’” she says in mock horror. “It’s almost overwhelming. The repertoire I’ve chosen is not something you can just shake out of your sleeve.”

She is especially looking forward to the close partnership with the Philharmonic musicians. “In the Mozart concertos, I will lead the orchestra myself, because it’s a much more direct way of music making. Mozart enjoyed performing his concertos that way so two hundred years later why should one not try to aim for the same kind of chamber music philosophy?” She will also perform an evening of chamber music including the Mendelssohn Octet, with the Philharmonic principals. “That will really be wonderful because they’ll be shown as the truly great solo players each of them is.”

In addition to her full slate in New York this season with the Currier premiere in the spring (“I’m still grinding my teeth and scratching my hair in total panic”), Mutter plans to explore the music of Syzmanowski and will add the Polish composer’s Violin Concerto No. 1 to her extensive repertoire.

“When I worked with Lutoslawski on the orchestrated version of his Partita he always referred to the Szymanowski concerti as pieces that were perfectly crafted and suited to my playing—whatever that is supposed to be!” says Mutter.

“It’s very poetically written. It has a lot of qualities that Lutoslawski was able to bring to the violin—it’s very serene and lyrical, very Romantic and colorful with the violin soaring above the orchestra. It’s pretty much the opposite of Gubaidulina, where you have to fight the orchestra off.” She plans to alternate the two Polish composers’ concertos for the coming birthday centennial of Lutoslawski in 2013

The violinist has also founded the Anne-Sophie Mutter Foundation to help discover, train and help gifted artists. “Our agenda is to find potential soloists. A soloist needs a very particular psychological profile and the gift to be unique in your approach to music and be totally focused on stage.”

Though it’s been many years since her last downtown appearance, Mutter retains a significant Chicago connection in that her glorious instrument, the “Lord Dunraven” 1710 Stradivari, came from Bein & Fushi, the celebrated local instrument shop.

“Yes, I bought it at Bein & Fushi in the 1990s. It’s still my main instrument and I’m totally, totally happy with it.”

But the ever-practical violinist–a mother of two teenagers—said she has no plans, as many renown string players do when in Chicago, to make a pilgrimage to the shop two blocks south of Symphony Center.

“I never try what I cannot buy,” says Mutter simply. “That’s always been my method of living a very healthy and good life.”

Anne-Sophie Mutter performs Beethoven’s Violin Concerto 7 p.m. Saturday with Riccardo Muti and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. cso.org; 312-294-3000